In his 2017 book The New Urban Crisis, Richard Florida pointed to an inherent contradiction in the neoliberal model of urban development. “Ultimately,” he wrote, “the very same force that drives the growth of our cities and economy broadly also generates the divides that separate us and the contradictions that hold us back.”1 Since then, the “force” that Florida referred to – which, to put it in the language of contemporary urban activism, is the force of extractive capitalism – has exacerbated the urban crisis even more. Waves of real estate privatization have washed over our cities and global private equity giants pump massive amounts massive of speculative capital into our cities, reshaping the urban lifeworld in the homogenizing image of investment opportunity. Particularly in the big international metropoles, decent housing has become an outright luxury, available only to those with premium incomes.

Against the background of the crises of war, pandemics, ideological polarization and social erosion due to rising economic inequality, the realisation seems to spread through urban society that the city should be more than just a territory for profit maximization. As the contemporary crisis deepens, so does the desire for meaning, community, reliability, and predictability.

Berlin, where I live and work, is no exception to this situation. However, over the past decade, a collective reaction to the forces of extractive capitalism is emerging, pushing against the excesses of finance-driven development models. There has been a veritable explosion of activities intent on saving the city from depredation by capital, often involving coalitions of citizens, activists, alternative developers and sensible local politicians. An important ingredient in this new and diverse brew of civic activism has been the emergence of alternative forms of real estate financing. Some of these financing models have been practiced for a long time, i.e., they are quasi-traditional, and are now being rediscovered. Cultural techniques such as lending, giving, gifting, bartering are reappearing now, often incorporated in contemporary forms of culture- or community-driven funding approaches, especially when it comes to financing neighbourhood developments in the real estate sector.

In what follows, I would like to first explore some forms of alternative financing very briefly in order to then turn to two recent development projects that I’ve been involved with in Berlin. In doing so, my focus will be on the question of how to use alternative forms of financing real estate development to create spaces in which something like communal luxury – based on collaborative making of the city for the sake of the common good – can thrive.

Community-based real estate developments that focus on building affordable housing, commercial space, social housing, community facilities and other social amenities often face massive financing problems. Fundraising is the crucial element of failure or success. As traditional banks are often reluctant to get involved in such projects, complementary and alternative forms of financing have to be found. At the same time, many content-driven and public interest-oriented project developers prefer, for ethical reasons, to stay away from the classical capital market and want to have as little as possible to do with the milieu of the financial sector. Some consider it downright damaging to their reputation to be associated with established players in the capital market.

As I’ve said above, there are a number of time-tested paths open to those who are looking for alternative financing. These include non-profit housing associations, cooperatives or foundations. In Germany, a country that has experienced a very prosperous second half of the 20th century and consequently achieved astonishing levels of private wealth, another curious development is happening in this respect. There is a generation of wealthy heirs who are using their private equity to purposefully invest in sustainable ecological, social and cultural development projects. A new class of ethically driven investors has appeared on the scene, made up of (mostly men) in the middle of their working lives, well-educated and earning dazzling incomes who are willing to forgo maximal capital return in order to enable initiatives that enrich the social and cultural fabric of the city. This is certainly a problematic situation as it places the decision of what does or doesn’t happen in the city in the hand of private money. It also raises the question of how this capital has been accumulated in the first place. However, my prognosis is that this kind of ethical investment will soon be a significant instrument of reputation-building among this class of investors. While ambivalent, it offers an enormous opportunity in the area of alternative real estate financing and is very likely to grow in the future.

Social Impact Bonds are another new method of financing that uses private investment to finance public projects such as the construction of affordable housing or commercial space. Investors receive a return on their investment if certain clearly defined social, cultural, community development and environmental goals are achieved. Finally, there are also the sustainability related banking sector that has experienced a significant push after the financial crisis of 2008, with institutions such as the German GLS Bank (“geben, leihen, schenken” – give, lend, donate!), the Dutch Triodos Bank, the Umweltbank, the Bank für Sozialwirtschaft, cooperative banks or similar financial institutions. There is a great potential for trust-based partnering of individual, cooperative and bank commitments in the provision of funds.

Clearly, each of these variants has its own advantages and disadvantages and requires thorough research to determine the best option for a particular project. Complementary combinations might often be the best way to go. In my experience, building mutual trust and stable relationships through common practice is the only way that works.

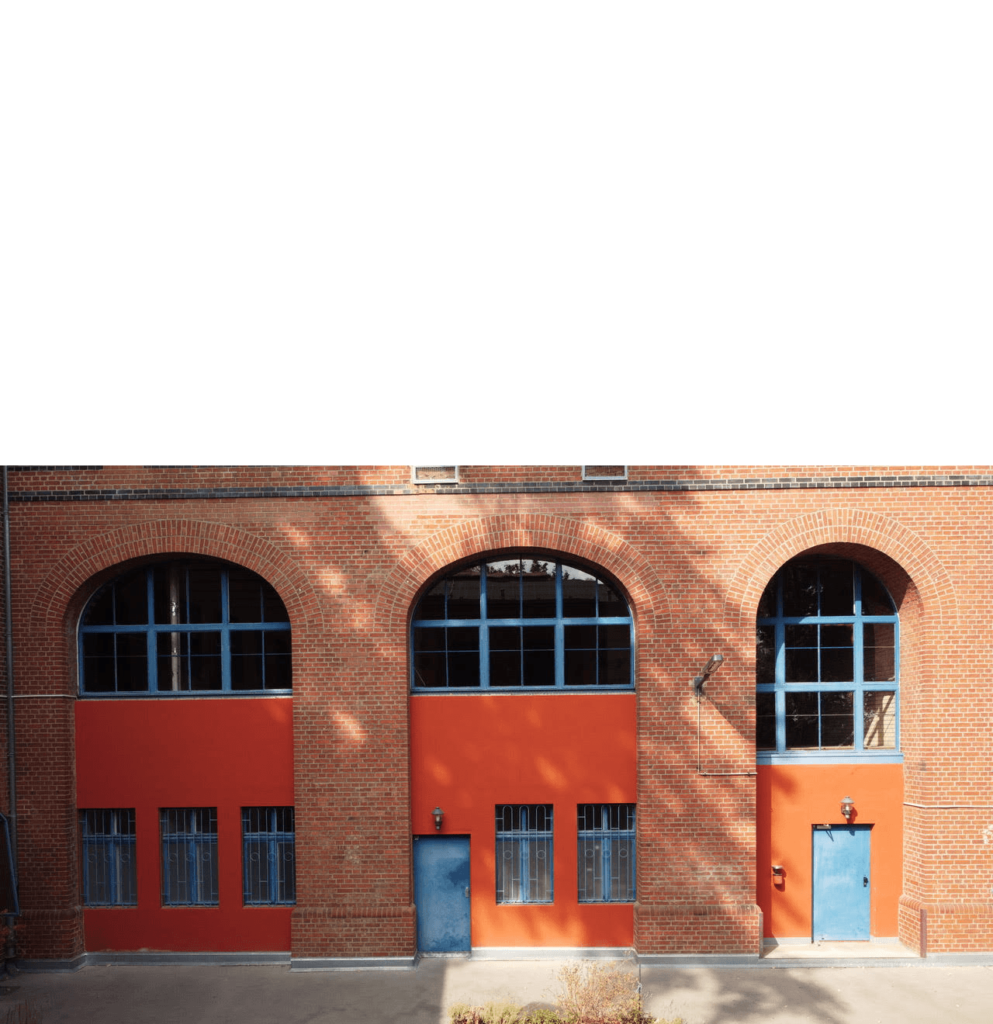

Moritzplatz Planet Modulor Aufbauhaus ©Neumann Rodtmann

Shortly before the collapse of the global financial market in 2008, the Berlin Senate awarded the former Bechstein piano factory at the central Kreuzberg Moritzplatz to Modulor, a dealer in architectural materials. The idea was to create something unprecedented: a physical department store for artists, designers and creatives as the centre of an ecosystem made up of shops, craft studios, companies as well as social and cultural projects. Then the financial crisis happened making the classical lending mechanisms unavailable for the project. What to do?

Modulor activated their media contacts and managed to draw the attention of several local and national newspapers to the impending failure of one of the most iconic non-corporate projects in Berlin’s inner city at the time. The ensuing publicity resulted in an agreement with a wealthy family from the Ruhr Valley who make a habit of investing their private equity into cultural projects (they later saved the former GDR publishing house Aufbau Verlag that also became part of the project as well). They jumped into the financing breach and helped this culturally-driven urban planning project to succeed. It was nothing short of a miracle back in 2008.

Once ownership of the building was secured, the future tenants – small entrepreneurs and activists – faced the challenge of converting and extending the space of the old factory. At that moment, an overwhelming wave of sympathy and support for the culturally-driven, common good-oriented project emerged, reflected in a broad-based crowdfunding campaign that achieved an initial capitalisation for many of the tenants. It also included a group of urban farming pioneers who tried to secure the plot adjacent to Modular that was later to become known as the Prinzessinnengärten. Building on this initial infusion of crowd-capital, it was possible to apply for grants from special development programmes at the city, national and EU-level. In addition, cooperatives, associations, companies and also foundations were set up specifically for the purpose of running the ecosystem, which, due to their non-profit status, were able to persuade private small investors, asset management companies and in some cases large foundations to help with the financing. A positive effect of the low-profit orientation of many members (not the new owners!) was also the effect of tax relief from the local tax office.

Today, the Planet Modulor/Aufbauhaus ecosystem stretches over approximately 25,000 square meters, hosting a variety of different shops, offices, a music club, theatre, bar, restaurant, kindergarten, artist studios, artisan workshops and publishing houses.

This case shows that if maximizing profit disappears as the main purpose, new and exciting forms of real estate development become possible by using a mixture of financial tools as well as involving an interested public in the planning process. This two-step model of financing – acquisition by a moderately-profit oriented party, followed by reconstruction and development with diversified individual fundraising – was successfully tried out here as a prototype.

Rudolfplatz substation wall ©Linus Krueger

The second example comes from a project that under normal circumstances would be well out of reach for a small time, culture-driven developer like us (Belius). It concerns a derelict electric power substation that was owned by Vattenfall. Located in the very heart of Berlin, close to Oberbaumbrücke and Warschauer Brücke, in the lively central district of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg that also hosts the Berghain Club, it is a large chunk of potential prime real estate. Wanting to dispose of the site, Vattenfall opened a limited bidding process in which Belius ended up as a wild card competing with four international investment giants. Our motivation for entering this process was the conviction that such a large project would give us a chance to combine a number of approaches we had applied in some of our projects hosting culturally driven entrepreneurs, social projects, artists and involving the local community (as, for instance, in the realisation of a market hall for the neighbourhood). Bringing these approaches together at the site of the former substation we saw an opportunity to show that non-extractive urban development is possible on a larger scale if one finds a way of exiting the overheated commercial real estate market. We were confident that we had a very strong concept but we also needed the necessary capital. Luckily, we found a partner in an old trading family from the north of Germany who have since turned their business into an investment operation for sustainable, cultural-driven real estate projects. With their financial backing, we won the bid. They acquired the property and committed themselves to a form of development that foregrounds the wellbeing of the city and is connected to the local community. This includes an extended amortisation time for their investment of at least 30 years which allows for the slow and organic development of the project. To get the development actually going, we’re now in the process of establishing a cooperative that will raise the necessary funds among its members. This will mainly involve recruiting non-voting investing members as the main financing source. One way of attracting members is the provision of highly subsidised special loans from state (investment) banks for the purchase of cooperative shares. This also enables those who lack the necessary capital to acquire cooperative shares.

Aerial view of Rudolfplatz substation ©Linus Krueger

In addition to the equity capital of the cooperatives, investment partners and private individuals, the development of the former substation will also require multimillion Euro bankloans. As single banks are reluctant to give out such loans in the current financial climate, we are in the process of organizing a consortium of ethical banks (Triodos and others) so that the financial risk can be spread and interest rates kept low. In addition, a foundation will be established on site during the redevelopment and construction period. Its purpose will be holding, preserving and operating this site – reselling will be contractually prohibited. In this way, the terrain and the building will be removed from the speculative real estate market – so that forms of communal luxury have a chance to emerge.

The above-mentioned examples of community-oriented, alternative real estate financing represent a current snapshot that might be rather specific to Berlin. At the moment, such developments often depend on the mutual trust of a few privileged yet progressively thinking individuals. The question is if more democratic and inclusive forms of financing could become structural. This remains the challenge of the next phase of sustainable public welfare-oriented financing. Right now, they are an alternative. We need to make them the norm if we want communal luxury for the many, not the few!