For more than 30 years my younger brother Patrick worked in the Shipping and Receiving department of a non-unionized factory in Northeast Pennsylvania. Early on in his employment, he and several of his co-workers spent their work breaks attaching newspaper clippings, snapshots, spent soda cans, industrial debris, trashed food containers and similar bits and pieces of day-to-day detritus to one wall of the plant. After a few years this accumulated clutter covered most of the wall. The workers christened their impromptu collage the Swampwall. The owner of the factory, an aging sole-proprietor in a world of mergers and multinationals, long tolerated this workplace diversion until a global corporation bought out his company in 1999. A structural adjustment followed. Dozens of “redundant” employees lost their jobs. The manufacturing division of the factory was downsized, services emphasized, and post-Fordist systems of inventory and just-in-time outsourcing implemented. Needless to say, Swampwall was expunged. And though its makers remained employed they were tasked with higher productivity as their pensions, sick pay, health care, and other benefits were reduced through privatization. Eleven years later, in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 Great Recession, Patrick died of a stroke at the age of 51. This reflection focuses on the production of Swampwall as a form of DIY protest “aesthetic” situated in the time and space of the day-to-day resistance of workers.

What was Swampwall? Notwithstanding the early 21st century popularity of de-skilled slack art –slap-dash post-it-note cartoons pinned randomly to gallery walls; clumps of ephemera or manufactured goods spread haphazardly over museum floors; recycled cardboard and cheap packing-tape sculpture; and paintings made to appear like the work of an amateur or Sunday painters—Swampwall was not art, not in any institutional or historical sense of that term. Furthermore, neither my brother nor his fellow factory workers ever attended college, and none had ever likely visited an art museum. Their collaborative frieze-like Swampwall was only visible to those employed or having business in that particular wing of the plant; an uninviting, sweat-soaked warehouse filled with forklifts, loading pallets, and packing crates far from the tidy cubicles and product showrooms of upper management. As a haphazard archive of the everyday, Swampwall most closely resembled a spontaneous memorial to dead time, which is to say, the time of not laboring for others or working to advance capital, but also in physics, it is the period after the recording of a particle or pulse when the detection equipment is simply unable to record another event, or in portrait photography, the interval necessary for a flash device to recharge itself. But insofar as these workers made manifest through Swampwall a desire to direct some portion of their energy elsewhere, just as they pleased, their contrarian activity also represented a desire for and a fantasy about autonomy. Not just any fantasy, not fantasy as illusion or self-delusion, but instead as Kluge and Negt point out, fantasy in the form of production, “throughout history, living labor has, along with the surplus value extracted from it, carried on its own production—within fantasy.”1

How differently we take stock of this jumbled artefact, this wall of daily detritus, knowing it was not intended for display in a museum or art gallery. This difference is very clear if we compare my description of Swampwall to the accolades celebrating the late artist Tony Feher (1956-2016) when he transformed “humble, “forgettable” materials that he finds—bottles, jars, plastic soda crates…into work that is rich with human emotion and fragile beauty.”2 Similar descriptions could be cited regarding the work of other artists who reject technical craft in order to highlight the unpretentious aesthetic of everyday objects or low-brow, pop-culture, or those who might collaborate with non-artists in celebrating DIY ingenuity which is introduced into the privileged spaces of high art. The ubiquitous presence of de-skilled slack art signals a changed relationship to the concept of the artistic amateur. However, as cultural theorist John Roberts perceptively points out, the professional who wants to appear ill-trained by performing the role of informal cultural producer is being out-maneuvered by the pace of technological change. Inexpensive digital technology now makes it possible for anyone to make near-professional quality graphics, movies, music, and even sculptures at their local makerspace. Meanwhile, the art world’s recurring post-war fancy for de-skilled practices should erase any lingering dishonor associated with the term amateur. As Roberts contends, today the professional artist “is now largely empty as a conceptual category,” adding that “we are now all amateurs, or professionals-as-amateurs, as the case may be.”3 This altered status has nonetheless not truly dented the art world’s hierarchical structures or led to a flowering of communal luxury in Kristin Ross’s terminology, that state of aesthetic experience which infuses everyday life. Or has it?

Before addressing this possibility, it is important to note that a factory warehouse with its numbing labor and fleeting jabs at freedom is not really such a strange place. Its invisibility to the everyday world is not mysterious. Instead, such spaces constitute a commonplace invisibility, one that most of us encounter, and many more of us participate in, on a regular basis, while at work, in school, as we pass through city streets, or enjoy a museum exhibition as we take the inconspicuous work of installers and movers and lighting technicians for granted. Think of this commonplace invisibility, or invisible commons, as a distorted shadow of the ‘real’ economy, a space in which informal modes of production, anti-production, cooperative networks of gift exchange, gossip, technology, and swapping, and the occasional instance of self-organized collectivism seek out the means of making life more bearable, sometimes under pitiless circumstances. And even if such sporadic creative expression seldom has a chance to develop beyond momentary outbursts of resistance, if one looks about carefully, we can see this other productivity everywhere. It radiates from homes and offices, schools and streets, community centers and cyberspace, most especially in cyberspace. It is like a missing creative mass or what I sometimes call the dark matter of contemporary culture. Think of this as an informal, dark matter therefore as a shadow version of Kristine Ross’s communal luxury, one that is operating at the interstitial level of our physical and mental reality.

Contraband radio

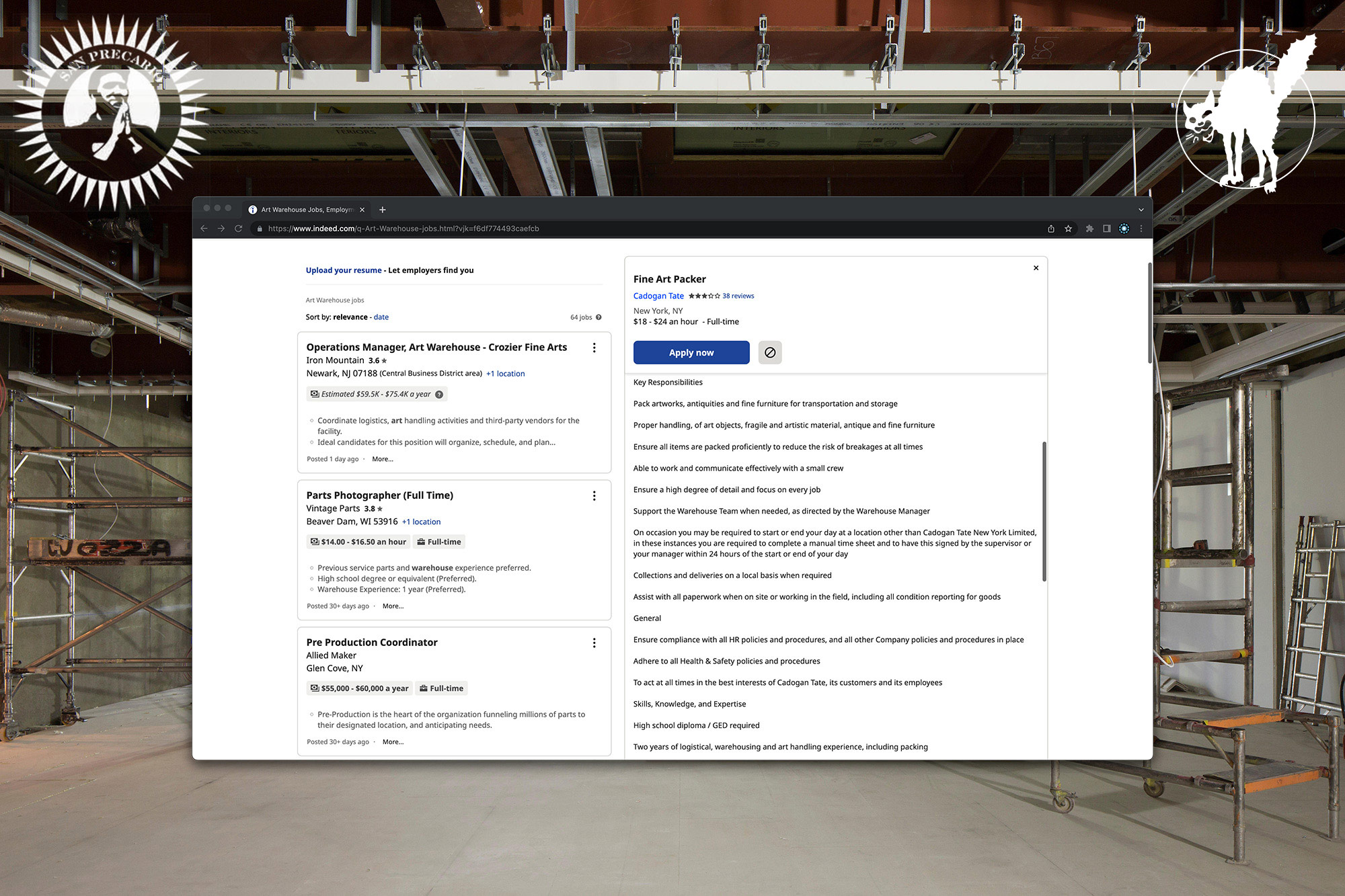

From ingenious contraband inventions made by prisoners out of paper clips, ball point pens, and toilet paper; to quilts cooperatively stitched together in support of voting rights, or in defense of a woman accused of murdering her husband; to the precarious margins of labor where teaching assistants, janitors, chain store workers, Amazon warehouse stowers, pickers and packers, art museum guards, greeters and installers, or Starbucks baristas furtively organize themselves under the downcast eyes of San Precario, or the wide open pupils of the Wobblies black wildcat; and most of all during the supposedly restful hours when working bodies are meant to reproduce their labor power through idle pastimes, yet remain awake instead to fantasize, organize, play, learn, and invent, in all these instances a hidden social production, and sometimes counter-production, have always inhabited their own time and space apart from hegemonies of power, the objectifying routines of work, and a culture that determines what is, and what is not, designated as valuable, useful, or profitable. This dark matter creativity is constituted by pleasure or by obstinacy, or both at the same time. Nevertheless, to the same extent, although in a less desirable direction, invisible social production via informal groupings, modes of participatory social cooperation, collective identities, can also be grounded in alliances of mutual exclusion, religious zealousness, ultra-nationalism and racist aspirations, as the rise of the Alt-Right has proven in recent years. Nevertheless, as either protest aesthetic or as a dead-time fantasy produced by resistant labor, Swampwall presents one possible starting point for a shadow version of communal luxury unfolding in both marvelous and unpredictable ways within the breaches and fractures of contemporary neoliberal society.