I have to be honest with you: I can’t tell a straightforwardly uplifting story about gaming culture, or the industry that produced it.

All the same, there are blooming gardens in videogaming; moving cocktails of time, place, and sense that will shatter you in the best way–if you open yourself up to them. While too much can be made of the “interactive” aspect of games, the fact remains that inhabiting the art is a signature of the medium, and this contributes so much to its beauty. You dwell in the artistic space and advance it. Aside from some modern art installations and performances (think Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece), there isn’t much in other media that quite compares with the agentic inhabitation of meaning you experience in video game worlds.

But this sense of self has also, perhaps, made us rather selfish creatures in each of these game worlds. To understand the gaming industry, you need to know two things about it: 1) It’s built on love, 2) this fact is considerably darker than it sounds.

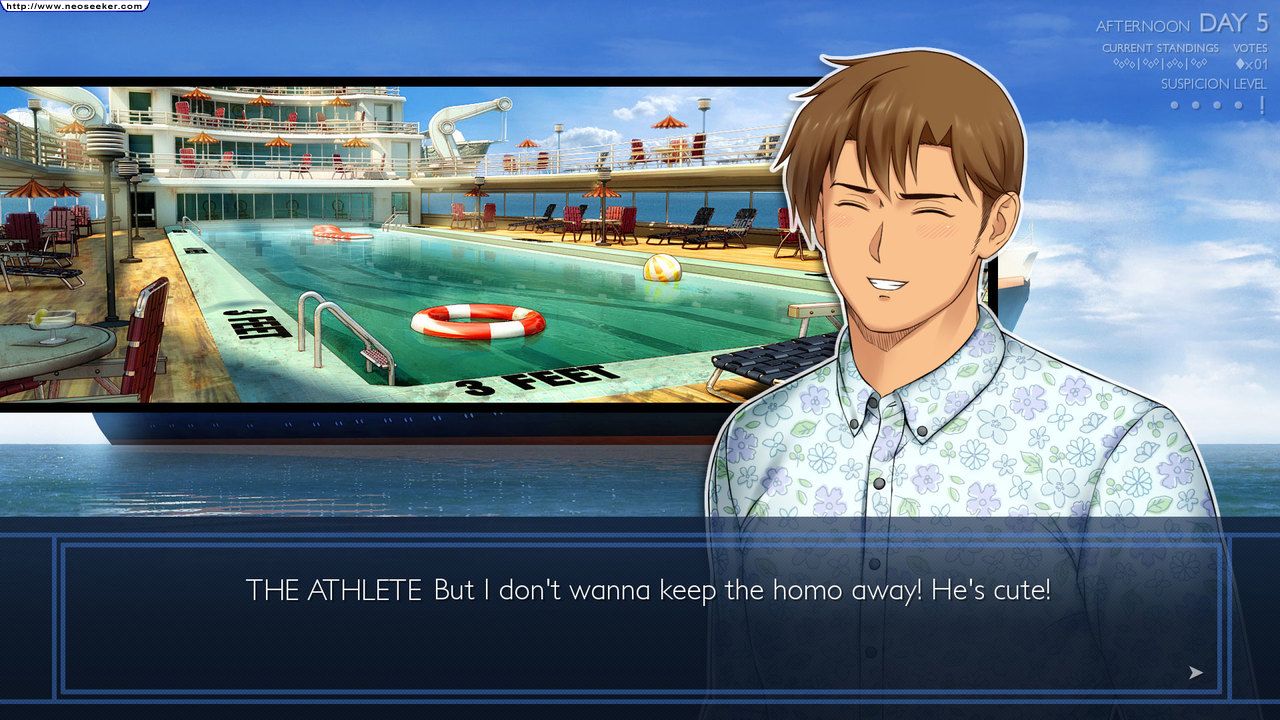

Screen shot from Ladykiller, on neoseeker.com.

There are many kinds of love that gaming engenders: the love of fandom, the love of creation, the love for creators, a love for the medium as a whole. And yet all love can easily turn to jealousy and possession, or become entirely self-referential: a celebration of mere possession and consumption rather than an engaged experience. Sometimes gaming encourages us to love the characters we identify with to such a strong degree that we lose ourselves in the process.

In his pathbreaking analysis, How Emotions Work,1 sociologist Jack Katz argues that emotions like anger are embodied and involve “a sensual transformation in which the body of the person becomes a new vehicle for experience.” He illustrates this through the example of road rage on Los Angeles freeways, arguing that the car becomes an extension of the driver’s body and that even the smallest faux pas–like getting “cut off” by another driver–is a profound insult, an “embodied loss” against what Katz calls a “seamless image of self,” a unity of vehicle, style, body, and personality, where each flows into the other. I’ve come to realise that video games work in much the same way and, much as car manufacturers learned to do in the 1950s, their studios play that up in their marketing.

The nature of games themselves, where you play as an avatar projecting herself limitlessly through space, easily analogises itself to Katz’s conception of the car. The avatar is not just what you’re playing; it’s you.

That is the nucleus of gaming’s beauty and terror. The infinite efflorescence of self that comes from this idealised avatar–who can fly into realms beyond your imagination–and the selfish fixation on your own existence that leads you to disregard all others, that treats any imposition upon you as a slur or as Katz’s “embodied loss.” That, indeed, is the source of so much online abuse. The angry player who yells at their fellow because he or she somehow inhibited their play, or did something they weren’t “supposed” to. Or, the angry player who threatens a game developer because she (or her colleagues) made a change to a game that made the player feel a fraction less powerful.

That’s player passion; but it certainly doesn’t affect us all equally. Queer people rebelling against a game with a troubling rape scene are of a different quality than whiny men threatening game devs because a trans character appeared in their game, or because a patch caused inconvenient bugs. Each case raises its own questions about how we’re embodied in a game, how “immersion” impacts us all differently, and whether collective identification and action are possible in a space that makes perfect individuals of us all. Is there room for more than personal fantasy? Is there space to move beyond lightspeed gratification to a place where art can flourish? Where angry young white men will no longer feel entitled not to be confronted with stories that challenge what they think they know? Where minority communities can speak our truths without fear or favour?

I think there is, in the end. But it requires us to think about the role of passion in gaming–how it leads us to strange and wonderful places where we can experiment beyond the boundaries of oppressive constraints, but also the profound limitations of such experimentation.

With care, such exploration can even break us free of the inherently individualising constraints of a medium that puts its focus on a figure in the shape of a solitary person.

Passion can take you in other directions, of course, out of the mainstream industry and into the wilds of indie gaming–a world of smaller studios or even one person outfits that have managed to make artful, fun, fascinating games.

When talking about the world of gaming in a broad way like this I like to conclude with what feels like a hopeful note: indie games channel passion in healthy and productive ways that make great art without being exploitative. But over the last few years it’s become clear how and why that’s, at best, an incomplete picture of indie gaming. At worst, it’s a malicious lie.

It’s certainly true that indie offerings demonstrate two things very clearly: first, it doesn’t take tens of millions of dollars to make a game that people will enjoy, as graphical realism isn’t required to have fun or experience a meaningful moment; second, that ‘playing it safe’ isn’t always the best policy–indie games have been queer, overtly sexual, racially diverse, and employed a range of mechanics, from being extremely difficult to having nearly none at all. Without institutional gatekeepers, smaller games have told bigger stories and found loyal audiences for them. Put another way, indie games are where marketing shibboleths turn to dust.

But there’s another reality to this world–one where passion becomes equally toxic, where developers are still viciously harassed (and without the benefit of even the thin institutional protections of major studios), and where being paid commensurate with one’s talents is a Holy Grail attained by only a few. No matter what precinct of the industry you occupy–whether offices in glass boxes drenched in fluorescence or the hipstery “scene” of independent development–you are subject to the whims of that vicious community of “fans.” Indeed, you can inadvertently create your own.

Merritt K, an indie developer, and Simone de Rochefort, a gaming journalist, described a worrisome case where a backlash to Ladykiller in a Bind, a game with strong queer themes, came from the queer community itself. A particularly dark scene, which depicted the complex and unsettling interiority of a character who was being sexually assaulted, was ultimately cut entirely from the game because of a fan backlash that said it had no place in the game. But, as K and de Rochefort explained in an editorial for Polygon, this comes at a cost:

[W]e keep demanding an impossible level of precision when dealing with messy topics, especially from queer developers; the backlash to this sex scene shows that the pressure is still on queer creators to write perfect queer experiences.

… Queer creators, like everyone else, aren’t infallible, and there’s always a place for criticism. But there’s a difference between analysis and nullification, between recognizing that a game isn’t for us and arguing that it’s irredeemably flawed. Too often it seems like larger studios are lauded for baby steps in matters of representation while women, queers and other independent authors are set upon for imperfect stories that actually hew closer to the realities of their audiences’ lives.

Speaking as a queer woman, this feels all too true. In an indie gaming world that thrives on micro-fandoms and intra-community art, we have to reckon with how even “our own” can become toxic fans who make entitled demands. Since we are expected to understand every vicissitude and challenge of queer life, we’re held to an unreasonably higher standard in the production of art about our existence–to a point where even its very authenticity can be seen as a flaw, as something a queer person ought not highlight or say out loud. This touches on a bundle of raw nerve endings that deserve far more space than I can give here, but the whole affair hints at how indie game production is no utopian refuge from the pressures experienced elsewhere in the industry.

What we expect in a “gaming experience,” what we feel entitled to, remains structured by a painfully individualist model that rewards loud voices, that treats art as a place for pure pleasure rather than one that admits discomfort as well. In the case of Ladykiller, this game explored the darker side of queer relationships, replete with immaturity, prejudice, and toxicity, while still producing a gaming experience that titillated with frank and lavish portrayals of BDSM.

But the scene that angered some players depicted the lesbian lead being forced to fellate a cis male villain, while providing us with a running commentary of her terrified and conflicted thoughts (at one point she wonders if she isn’t enjoying this on some level). It’s easy to see why it rankled–though it was hard to argue that the internal monologue was promoting rape. It could be argued that it was dissonant with the rest of the game, but its humour always bore a serrated edge–the game was about trauma, dark emotions, and terrible people, and it’s rare that we get a queer game from a queer perspective that touches on such ugliness.

It’s worthwhile to debate whether a game that catered to sexual fantasy should also have been a game that explored sexual darkness, but it seems a shame to have left a more complicated discourse lying there under fifteen feet of pure white Twitter discourse from last winter. Unpleasant feelings linger, however. K and de Rochefort quoted other queer devs who fear the same thing happening to them if they tell messy stories.

It may be that this particular issue is, itself, the result of intolerable pressures created by a dearth of queer art in the world of gaming. We get so little that we demand perfection from what we do receive. And thus, in the end, the gatekeepers on high get the last laugh, for their restrictions and censorship curse us even when we think ourselves free of their influence. Even those of us long outside of, and excluded by gaming culture, succumb to its tune. In the words of one of my favourite video game characters, “so long as the music plays, we dance.”

Can gaming simultaneously give us queer fantasy and queer realism at the same time? I should hope so. But when we consider Katz’ framework for emotions, and how that applies with particular viciousness in the world of gaming, it’s worth evaluating just how much of a challenge that creates for queer art in this space. These issues create a pressure cooker of impossible expectations that routinely boils over.

The nature of the avatar is to act as a canvas for the player’s emotional projections. As a figure of fantasy, it is the ur-individual, forever extending herself towards limitless digital horizons. She is invested with profound powers, eternal life, and–often as not–an idealised form. Intrusions upon her feel abidingly personal, imbued with all the cosmic unfairness of a papercut or being cut off on the motorway.

These intrusions come in two broad forms. One is the imposition from another player–say, a demand for better portrayals of minorities impinging on your sense of how awesome your favourite game already is, or perhaps it’s a fellow player ganking you, stealing your kill, or being a loot-ninja. The second is the game itself imposing on you, inhibiting some sense of your own power and fantasy–and it’s this second class of intrusion that Ladykiller’s rape scene belongs in.

In the case of Ladykiller, the game had, despite its self-evident darkness and the despicability of its characters, acted as wish fulfillment for many of its queer players. It was that nebulous thing known as “good representation.” Then along came a jarring scene that wounded the player’s straightforward identification with the protagonist, The Beast; suddenly she wasn’t a fun person whose shoes you wanted to stand in, but a victim with terrifying thoughts. The darkness was no longer edgily ironic; it was just plain dark. It was a place that queer rape survivors didn’t want to go, certainly. But this was about more than dealing with triggers for personal trauma; it was about a queer fantasy that was tarnished, an avatar whose perfection was suddenly troubled. That was what gave force and numbers to the backlash.

Ladykiller raises legitimate questions, of course. There’s an argument to be made that the scene was too dissonant, its pitch-black humour out of step with the rest of the game, and ultimately Love herself made an artistic decision to remove it, which could be seen as a validation of such critiques. Asking a sexual assault survivor to inhabit such a scene feels almost cruel, precisely because games are so involving, because our avatars are extensions of ourselves, whose pain we feel acutely (though Love had long ago included trigger warnings and made the scene optional).

Portraying sexual assault is fraught, and perhaps this was the wrong kind of game in which to do it. But that just raises the question of what the right kind of game would be.

A dark but essential truth was captured by the now-deleted scene: queer rape survivors do not have perfect thoughts, and our social dislocation reproduces itself in horrifying ways as we’re experiencing trauma. The Beast was shown as struggling with aspects of her own identity under the worst possible circumstances, thrust into doubt and self-loathing, possibly sexualising it as a defence mechanism. This is bleak stuff, but it’s also true to what some survivors experience. We are not perfect avatars fulfilling wishes, but people who labour under incessant attempts to thwart the power of our humanity. Without going into too much detail, the ugliness of that scene spoke to me on a personal level. I saw myself and my own experience of sexual assault in it; now it’s gone.

The thwarted avatar is a fascinating figure.

Naturally, the point of a power fantasy is that it offers players a respite from the limitations of everyday life, but there can still be something strangely liberating in the way video games can curb the power of players. Being a limited, ordinary human remains a very different experience of power from, say, roleplaying as a limited Jedi.

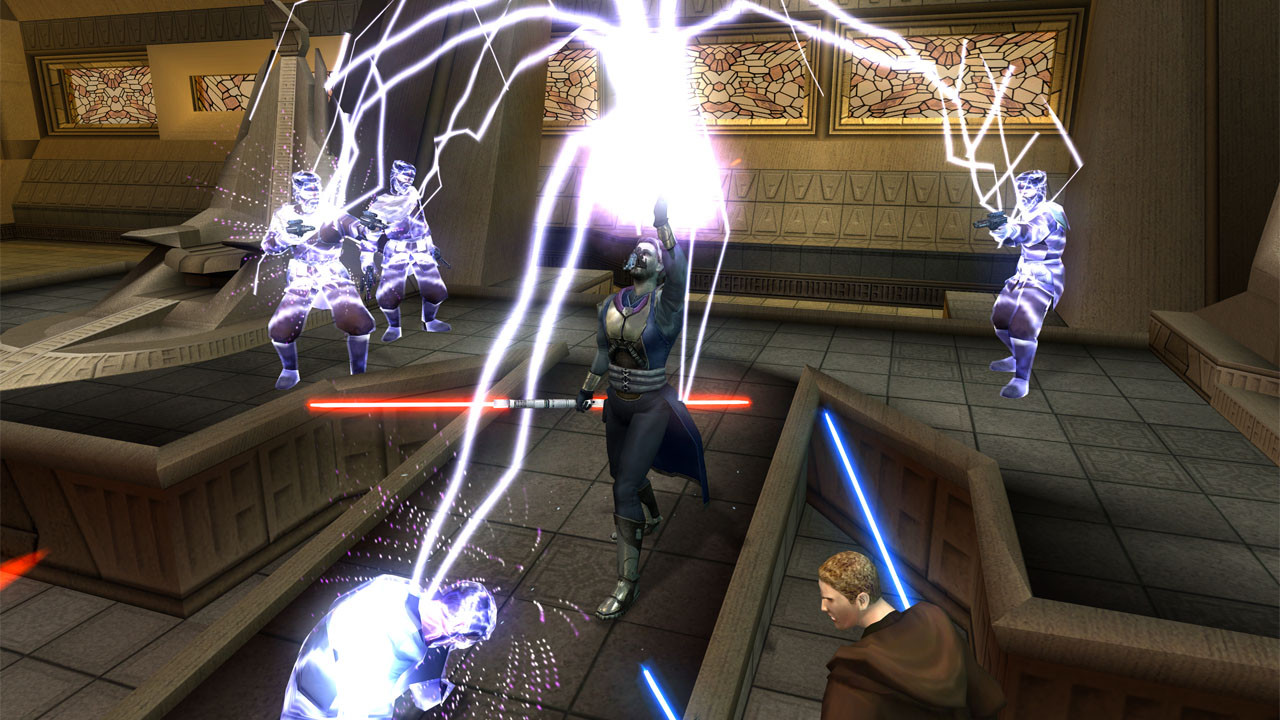

Screenshot from Knights of the Old Republic 2

In Knights of the Old Republic 2 [KotOR 2], now a classic in the roleplaying genre, you play The Exile: a Jedi outcast from her order for fighting in a war she’d been forbidden from. Though the cause was just–fighting to save the Galactic Republic from the rapacious Mandalorians–it cost her everything, including her connection to the Force. Thus, this is one of a few games that credibly justifies your character starting at level 1. The Exile has to relearn her iconic Jedi powers from scratch–with the aid of a teacher: the mysterious Kreia.

What results from this relationship is not only one of the most compelling, and unusually mature Star Wars stories ever told, but an incredible reflection on the nature of video games themselves.

Your character does, indeed, become a power fantasy. She cuts down foes with breezy lightsabre strikes and harnesses the Force to explosive effect. But in the end, she can’t do everything. In one iconic moment–one that is sometimes derided or satirised by fans–The Exile is confronted by a beggar and you’re given a moral choice between giving him a few credits or threatening him. What upset many players was that, no matter which choice you made, you’re treated to a cutscene where some misfortune befalls the man, each tied to your choice. If you give him money, he’s mugged by another homeless man; if you don’t, in his rage, he attacks another destitute fellow.

In each case, Kreia uses the incident to teach The Exile (and, arguably, the player) a critical lesson about power: you cannot control every conceivable outcome. What outraged some fans was precisely this fact–no matter what they did, their intervention, their mere presence in this hopeless place, had sent out ripples (or “echoes,” in the game’s preferred metaphor) with unpredictable and undesirable effects. Though this is the most (in)famous example from KotOR 2, there are others as well. The game’s climax reveals Kreia to have been manipulating The Exile from the start for her own ends–both to save the galaxy and to further her arcane philosophy on the Force. Some players felt like this cheapened their actions in the game, depriving them of the illusion of free will that surrounds most ludic power fantasies. Critically, in an RPG driven by choices, the player is revealed to have no choice.

KotOR2 brought to its surface a reality endemic to all such games. Your choices are always constrained; choice itself is often illusory and meant more to offer both flavour and the mere sense of control. The game even made a meta comment about experience points. One Jedi elder tells the Exile that she is diseased in part because she “killed hundreds, only to become more and more powerful,” feeding off of the desolation. This is the core development mechanic of most roleplaying games, and the game asks you to feel a certain ambivalence about this.

KotOR2 uses the structure of a classic power fantasy story to ask us to reflect on the limitations and ethics of power. You cannot fix everything, and your actions have unintended consequences, even when you can single-handedly take on a battalion.

Screenshopt of Dragon Age 2

Dragon Age 2 [DA 2], also received with some ambivalence by the gaming community, was another meditation on this point. Your character, Hawke, is powerful and grows moreso over time–even inheriting a fancy manor in the posh part of town where she can share intimacies with one fetching lover or another. And yet, when it really matters, she has no real power. She is, indeed, powerless to truly shape the events of her city. Instead, she is breathlessly catching up to the agendas set by others, reacting to events rather than mastering them. This was deliberate, and meant to show the world of Dragon Age from the perspective of someone who–while strong–was not a world-historical figure.

Power is rarely absolute and, when it is thwarted, the resulting tension is beyond intoxicating. Though many gamers condemned aspects of DA 2’s gameplay, they rarely found fault with the characters. Their relationships crackled with the awkwardly tense authenticity of real people living under pressure. Even though they were all in their own ways much more powerful than the average peasant in Dragon Age, they were not pulling the grandest levers of power and were always at risk of being swept up by floods sired by the actual ruling class. It made them relatable, their tensions and anxieties believable. It also marked a watershed moment for Dragon Age’s sizable queer fandom, where the deliberate messiness of many of these characters, along with their availability as same-sex romances, led many of us to relate to them on one particularly deep level or another.

Of course, it must be noted, some of DA2’s ‘constraints’ aren’t artistic, but the result of the game being rushed through its production cycle. Forcing a player to stand by helplessly to ensure the plot can proceed—killing a sympathetic character in front of them, say, and temporarily suspending their power so that this necessary moment can proceed—is not an elegant examination of the limits of power, but a lazy way to tell a story in a video game. It’s a joint where narrative and gameplay have been fused poorly. This is certainly the case when Hawke’s mother is murdered in a particularly grisly way by a misogynist serial killer; Hawke was, naturally, powerless to stop him. To constrain the player in this way is to inject cheap pathos into a story without earning it as a narrative payoff.

But the larger themes remain undimmed by this grim concessions to ruthless development cycles, and both DA2 and KotOR2 deliberately explore thwarted heroism in interesting ways. In the process, games like DA2 also tell stories that feel authentic to the lives of those who feel their power to be constrained, while still providing escapism to dull that very same pain. For queer people, there is something extra precious in that experience because it reflects the shape of our pain.

This, then, is what games can do spectacularly well: they can allow us to explore the beauty of the imperfect. Which, not coincidentally, is essential to telling authentic stories about marginalised people. To maintain even the illusion of perfection is a privilege; the manifest nature of a queer person’s imperfection, by contrast, is so often seen as licence to abuse us. We are, from the first, constructed as abnormal, unnatural, illegal, or even monstrous. Telling that story requires an embrace of glitches and untidy narratives. Just as historian Susan Stryker reclaimed the figure of Frankenstein’s monster for trans women, so too might we reclaim the broken avatar as the truest vision of a digital queer self.