Can music change the world, or do we just want to believe it can? Although popular music has never by itself brought about social transformation, it has a long history of soundtracking and documenting aspects of social change and contributing to attempts to imagine and construct social, cultural and political alternatives. Music has the capacity to reflect and amplify existing struggles and to form part of alternative subcultures. However, political expression through music is often confined to subcultural niches which define themselves more broadly in opposition to mainstream culture and politics, while within the traditional music industry, the success and visibility of artists has frequently depended on their acquiescence with commercial manipulation and malleability. Music which has gained visibility or significance as part of rebellious or oppositional movements, meanwhile, has been consistently coopted and recuperated by these same mechanisms. Music or artists may be given a veneer of pseudo-radicalism in order to lend them a commercial edge, and innovations developed by marginalized subcultures are rapidly appropriated by the mainstream industry.

While music has formed an intimate and integral part of social and cultural development, the growth of popular music into an established industry has been bound up with technological innovation: from the techniques of amplification which enabled artists to play to mass audiences at festivals or stadium gigs, to the use of turntables and sampling in the development of hip hop, to synthesizers allowing both the replication of traditional instruments and the creation of new sounds. For musicians, the growing availability of music development apps and software has granted individuals the ability to compose, mix and record music in a relatively cost-effective manner. Coupled with the access provided by the internet to almost infinite resources of music and culture present and past, and the ability to make music available through social media and digital distribution, these developments have rendered producers and record labels increasingly redundant. Music can now be produced and disseminated by artists themselves – not, of course, with the same level of resources and reach as a traditional record company, but with greater creative independence and often with a more direct connection to their audience.

The transformative capacity of these new platforms, channels and networks can depend on the uses made of them at any given political moment. In the past few decades, popular music – along with other sectors of the arts and media – has been marked by the narrowing of access to ‘traditional’ routes to mainstream stardom, as artists increasingly require preexisting connections and independent wealth to establish themselves in what can be a precarious and competitive field.1 However, alongside this restriction of access at the top, the growth of mass internet access in Britain has had the effect of democratising the production and consumption of music, allowing individuals to circumnavigate the requirements for industry resources or connections as a means of producing and accessing culture. Although constrained and compromised by corporate ownership of social media platforms, the increased visibility of artists from marginalised demographics or communities has given them the ability in turn to make systemic social and political concerns more visible in pop culture, for instance through lyrics referencing racism, including racial elements of police harassment, and the impact of austerity on the already disadvantaged. One recent and spectacular example of how this kind of community-forming and process of articulation can have politically transformative effects was the intervention of the UK grime community in the general election of June 2017.

Screen shot from Wiley Ft Devlin - Bring Them All / Holy Grime VIDEO | View

The grime scene had its origins in East London’s council estates in the early 2000s. With its roots in UK garage, drum n’ bass, dancehall and ragga as well as hip hop, grime is characterized by its sparse, off-kilter, yet powerful and cathartic sound, and by an often irreverent and confrontational energy which has seen comparisons drawn with punk. Initially known by a variety of names including 8-bar, sublo, and eski, grime gained in prominence throughout the 2000s with the increasing success of Wiley and his protégé Dizzee Rascal, both from Bow in East London and drawing on the location in their work. The emergence of the early grime scene was driven as much by inner-city boredom, desire for social recognition, and the enthusiasm for creative and representational possibilities which making music offered, than by the wish for commercial success. A respondent to a 2017 survey of grime fans characterized the genre’s subject matter as “just everyday life”, but a quality of life which seldom received mainstream expression or representation: “Stuff you don’t see or hear in the news and TV. A part of the country always sheltered and hidden away like a bad secret”.2

Grime artists adhered to DIY methods of recording and distribution: freely circulated mixtapes, freestyles uploaded to YouTube for free consumption, the independent DVD showcase series Lord of the Mics, and pirate radio stations including Déjà Vu, Raw Mission and Rinse FM, whose creative freedom and lack of censorship helped MCs shape the genre’s sound.3 Grime’s focus on representing one’s local area or neighbourhood, both in lyrics and through the formation of local crews, and the significance with which individual actions were regarded by the scene as a whole, also gives grime a sense of collectivism and communality. The genre saw a surge in celebrity and popularity from 2016 – the year of Skepta’s Mercury Prize win and Stormzy’s Gang Signs & Prayer becoming the UK’s first grime album to reach number one – with artists moving from pirate radio to platforms like Soundcloud, and the spread of the genre outside London to other urban centres including Birmingham and Manchester. Despite this greater attention and prominence, much of grime remains independent and outside the music industry’s traditional boundaries. It is arguable that the recent wave of UK hip-hop and grime artists have been able to successfully negotiate the conflict between mainstream success and local legitimacy – a disconnect which contributed to the demise of the early UK punk scene – through using social media to retain a local connection, as well as to give the impression of an unmediated personal dynamic with their listeners.4

Like jungle and UK garage before it, grime is a distinctly and idiosyncratically British genre which, although black British in its origins and primarily in its audience, can appeal across boundaries of race and ethnicity. The conception and reception of grime as inherently subversive or disruptive, however, is inextricably linked in part with London’s history of tension and hostility between police and the city’s working-class and BAME communities. The Metropolitan Police’s Form 696, which collects performers’ names and contact details and which initially attempted to racially profile the likely audience for particular events, was widely seen as a targeted attempt to harass or prevent live grime events and performances. This bore comparison with attempts by John Major’s government to use the 1994 Criminal Justice Bill to clamp down on public raves and mass gatherings involving music characterized by “repetitive beats”, and displayed a similar though more racially-inflected suspicion of counter-cultural music.

However, the radical and oppositional presence often perceived in grime is also a function of its ability to draw together aspects of class, racial and cultural identity and representation. This broader appeal is rooted in grime’s articulation of a particular working-class British – particularly London-based – identity and lifestyle, and a consciousness shaped by the “ravages and destruction” of the 1980s and the socioeconomic division produced by inner-city neglect and gentrification which followed.5 Journalist and grime fan Hattie Collins detects the importance of these tensions in the genre’s emergence from East London’s impoverished council estates, which exist in the shadow of the symbolic wealth, power and influence of Canary Wharf and the city’s financial district.6 Mykaell Riley similarly categorises grime as “the sound of social deprivation emerging from the shadows of re-urbanisation and gentrification”, and grime artists and fans have linked their scene – often ironically – with the invocation by right-wing media and politicians of a socially dysfunctional “Broken Britain”.7 Although seldom explicitly political, and invariably taking an anti-establishment stance which rejected parliamentary politics wholesale, grime lyrics frequently give expression to the kind of alienation, disaffection and anxiety among the young urban poor that mainstream politics, media and culture has done little to acknowledge or address. In 2010, the spontaneous playing of grime tracks during student protests was remarked upon as an illustration of the continuing existence of music which could be received and repurposed as politically confrontational, despite the disappearance of these sentiments during the same period from the British guitar-rock where they had formerly been prominent.8 Often, the creative and commercial possibilities of grime themselves offered artists strategies to articulate, confront or transcend the social and political limitations placed upon them by the intersections of race and class.

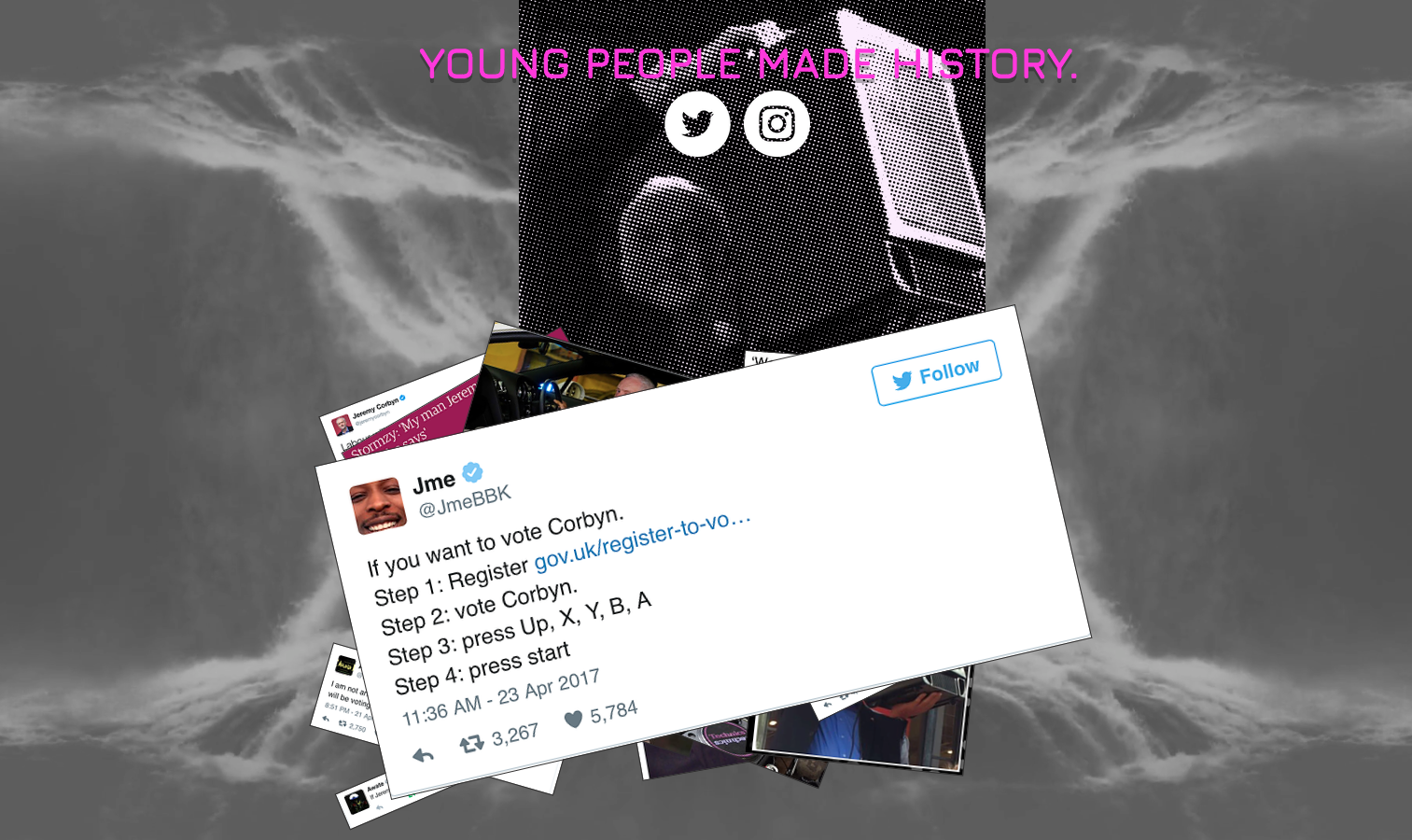

In 2017, grime’s nebulous anti-establishment defiance took on a more solid form. The UK general election on June 8th saw increased turnout by young voters, overwhelmingly in favour of the Labour party. A notable factor behind this was the support given to party leader Jeremy Corbyn by UK grime figureheads, and the amplifying of this support online by their fans and followers. In 2016, during Corbyn’s embattled first year as Labour leader, as he faced successive challenges from his party’s right wing, he also attracted public praise from grime MCs including Stormzy and Novelist, who complimented his approachability in contrast to the corporate slickness of David Cameron, as well as Corbyn’s history on anti-apartheid campaigning and concern for vulnerable demographics.9 In the run-up to the following year’s election Jme, co-founder of the grime collective and independent label Boy Better Know, endorsed Corbyn on social media and held a meeting – recorded and later made publicly available – at which the two discussed music, education and the arts as well as how to increase political involvement among young people. The interest and publicity this generated was followed by the website www.grime4corbyn.com, which aimed at encouraging voter registration and featured a speech by Corbyn set to a grime-style backing track, and the appearance around London of pro-Corbyn posters and graffiti which drew on grime aesthetics. Online, memes and viral videos used similar techniques to tie together enthusiasm for Corbyn and grime, while grime artists themselves made Twitter, Facebook and Instagram posts backing Corbyn and Labour, resulting in the #grime4corbyn hashtag receiving greater use and attention than official ones, including #LabourManifesto.10

Screen shot from grime4corbyn Website

The Grime4Corbyn phenomenon seemed finely balanced between, on the one hand, an often gleeful awareness of the inherent incongruity of combining a subculture associated with young, BAME and primarily apolitical or anarchic adherents with a veteran socialist politician often derided as outdated and unfashionable, and, on the other, the assertion of a genuine compatibility between the concerns of grime’s core demographic and the politics presented by Labour under Corbyn. A central factor in pro-Labour enthusiasm was the chance it offered for new or disillusioned voters to meaningfully engage with electoral politics and political parties, following a period in which the political agency of young people – and of any voter seeking an alternative to neoliberalism – had found little or no constitutional outlet. Under Corbyn’s leadership, Labour offered a decisive break with the prevailing neoliberal consensus through a politics which emphasised social justice, wealth redistribution and anti-imperialism, all of which struck a chord with “Generation Grime”.11 This allowed the party to be more convincingly presented as a radical alternative than had been the case for several previous electoral cycles, which had been dominated by the kind of centrism and stagnation to which grime’s jaded dissatisfaction with the status quo and contempt for all politicians was partly a response. The artist and activist Akala’s much-publicised endorsement of Corbyn, for instance, emphasised his own previous disconnection from electoral politics and the chance at an alternative, leading to substantial material change, which he considered Corbynism to offer.

As Mark Fisher has identified, the uncoupling of class consciousness and class-based politics from those of race, gender and sexuality has been fundamental to the advance of neoliberalism.12 This made it all the more significant that grime artists and fans expressing their support for Labour did so by prioritising Corbyn’s “policies, humanity and voting record”, as well as his perceived lack of personal ambition, over a straightforward politics of identification.13 They also saw their lived experience as constrained by youth and class as well as by racial inequality – and by identifying how poverty, unemployment, police animosity, and lack of access to housing and higher education demonstrated the connection of all three factors.14 The Grime4Corbyn website similarly focused on these material intersections, highlighting the prospect of “elect[ing] a Labour Prime Minister who will reduce the voting age to 16, cancel exorbitant university tuition fees, cancel zero hours contracts, and through a new genuine living wage and building 500,000 council homes a year, give Britain’s young people the homes, jobs and education they need”. In addition to the political content of Corbyn’s offer, it is possible that the form of activism which support for Corbyn generated, stressing the role of non-professional grassroots groups and extraparliamentary social movements, also meshed effectively with grime’s emphasis on self-sufficiency and DIY culture outside an establishment or mainstream.

In its intertwining of musical subculture and radical politics, Grime4Corbyn is of course not unprecedented in UK popular culture. Perhaps its most obvious point of comparison is Red Wedge, a collective of progressive musicians aiming to encourage political engagement and support for Labour among young people in the years before the 1987 general election.15 Despite being far looser, and more spontaneous and self-sustaining than Red Wedge, Grime4Corbyn nevertheless demonstrated an updating or acceleration of music’s ability to engage and unite disparate individuals, to represent marginalized voices and identities, and to galvanise them towards political action, in a manner frequently claimed to have been lost in comparison with earlier protest music. It could not have done so with such speed, visibility and momentum without its use of social networks and digital platforms. Grime4Corbyn is therefore one example of how changes in technology, and the impact of these changes on the production and consumption of music, can be adapted to empancipatory political strategies, making use of the connections and collectivities available to otherwise atomised supporters, activists or sympathisers through new social media platforms, and offering a sense of contemporary British identity which draws together consciousness of youth, race and class.

In its use of viral memes, videos, mash-ups and hashtags to raise awareness of the election and the issues involved in it, and to encourage voter registration and support for Labour, the Grime4Corbyn movement shares elements of the broader ‘cyber-populism’ identified in the use made of social media by anti-austerity and left-populist activists in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. This strategy involved the deliberate use of Facebook, Twitter and other corporate platforms by activists in order to put forward simplified versions of political arguments, to sloganize, and to mobilise for actions offline, in a manner that could be shared and spread quickly and widely both by activists and by non-aligned individual supporters or those whose imaginations were captured by the arguments made.16 The risks and drawbacks of this strategy quickly became apparent in the surveillance and censorship enacted on the pages and accounts of protest groups and activists, and the recent turn by social network sites towards prioritizing the placement of paid content indicates the diminishing opportunities for similar attempts by non-profit groups. However, such examples also demonstrate how corporate platforms may be utilized for left-populist mobilization, if only for limited and temporary moments of success.

The immediate result of Grime4Corbyn was a visible increase in voter registration and turnout among young people – over a million of whom registered to vote following the announcement of the election – and its consolidation in support for Labour, which made a major contribution to the party’s unexpected electoral success. A 2017 study found support for Labour among 58% of grime fans, with one in four stating that their Labour vote had been influenced by Grime4Corbyn, and those aware of the campaign more likely to be young and BAME.17 Grime, then, can conclusively be said to have provided a soundtrack to the political upset and disruption signified by support for Labour in June 2017 – and to have been driven to a certain extent by similar discontent with the political status quo and a similar wish to seize the opportunity to instigate change.

The success of Grime4Corbyn demonstrates that, despite the increased commodification and commercialization inherent in new social media platforms and channels of distribution, these developments can enable both self-expression and representation by individuals and collective political influence and mobilization. However, the political efficacy of these ‘cyber-populist’ strategies is also clearly limited, both by their focus on short-term objectives and by the primary function of social media and new technology as a means of corporate marketing and monetization, as well as its fostering of a propensity for superficial analysis and solipsism among its users. The momentum generated by Grime4Corbyn was ultimately a symptom and reflection of a longstanding and deeply-rooted political malaise which will take equally systemic and long-term work, with a probable long-delayed payoff, to resolve – although the increase in voter registration is an encouraging achievement to build on. While disconnected moments of political disruption, assertion or opposition can be significant, they often lack an underlying coherent framework or conceptual analysis to which these moments can be tethered. The conscious use of social media for political expression or organization must take account of this if it is to construct effective arguments for more substantial and systemic change.