The Dadaist should be a man who has fully understood that one is entitled to have ideas only if one can transform them into life – the completely active type, who lives only through action, because it holds the possibility of achieving knowledge.

We are not the PDS, not the democrats, we are the PBS, a new party.

In 2013, superstar rapper Jay Z teamed up with performance artist Marina Abramovic to shoot his music video “Picasso Baby” at Pace Gallery in New York during the run of her “The Artist is Present” retrospective at MoMA. The following year artist Kara Walker guest-curated Ruffneck Constructivists at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Pennsylvania, placing Notorious B.I.G’s Ten Crack Commandments in dialogue with the Futurist Manifesto. Subsequently, in 2015 Kanye West’s collaboration with renowned director Steve McQueen “All Day / I Feel Like That” was screened at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Hip hop culture seems to be increasingly present in spaces for contemporary art as key figures from both worlds collaborate. Beyond the bombastic improbability and glamour of their fusion, however, this recent love affair needs to be understood in a nuanced way. It would be short-sighted to ignore the threat of cultural and financial appropriation by a majority white art world of a multi-facetted culture that was born within Black and Latino communities of the Bronx, at a gaping distance from the white cubes of Manhattan.

Perhaps the clue to understanding this “hip hop turn” lays in the fact that more than any other musical form or cultural genre of the last century, hip hop has shattered the barriers between art and life, fulfilling the aspirations of twentieth century avant-gardism. As the contemporary art world desperately searches for its soul amidst an increasingly intense climate of political and social crises across the globe, and debates over the relevance of socially engaged art practice are exhausted, hip hop culture’s capacity to fuse art and life make it a productive reference point for this existential turbulence.

To make sense of this hip hop turn, we must travel further in time from the Bronx of the late 1970s back to Dada. Drawing parallels between Dada and hip hop culture sets the stage for understanding broader cultural tendencies from the last hundred years, and the role that hip hop plays in this trajectory. One of the most striking similarities between hip hop and Dada is the emphasis on the gesamtkunstwerk and interdisciplinarity. In the late 1970s DJ and producer Afrika Bambaataa originally coined the four aspects of hip hop cultural production: Rapping, break dancing, graffitiing and DJing, with “knowledge” arriving afterwards to complete what is now known as the ‘five elements of hip hop’. Similarly, the Dadaists strove to disrupt hierarchies of artistic expression by collapsing separations between body, sound and the visual in performances that rejected “high art” and the academic imaginary.

The very naming of Dada and hip hop is also noteworthy, both being invented words that escape fixed meanings of existing language. Such a disregard for established norms of language additionally captures the mobilisation of language as medium in both contexts. As Hugo Ball stated in the 1916 Dada Manifesto, “The word, gentlemen, is a public concern of the first importance”. Hip hop’s investment in the word and the privileging of wordplay as well as marginalised language, gestures to similar semantic commitments.

The way in which hip hop vernacular is present in the mainstream today reveals the success of hip hop in imposing its form within society at large. Most crucially, when looking at the genealogy of Dada and hip hop, Dada was articulating a means of expression that would shake up the psychology of the status quo gripped by world war. Unafraid to shock, art was supposed to barge into the realm of life for Dadaists. From Black Mountain College to Fluxus, the movements that have become recognized in the canonical history of artistic avant-gardism, all grew out of this notion. In parallel, hip hop has unapologetically taken on this mantle and propelled it to a global scale. Hip hop culture has influenced generations to take up arms, to put them down, to spend dizzying sums on cars, clothes and villas, to donate those same dizzying sums to community relief projects, and to both reject and enter into politics. Its fusion of aesthetics and everyday experience place it in a unique position to potentially satisfy the ambitions of Dada’s proponents, particularly from the perspective of an existentially fragile art world.

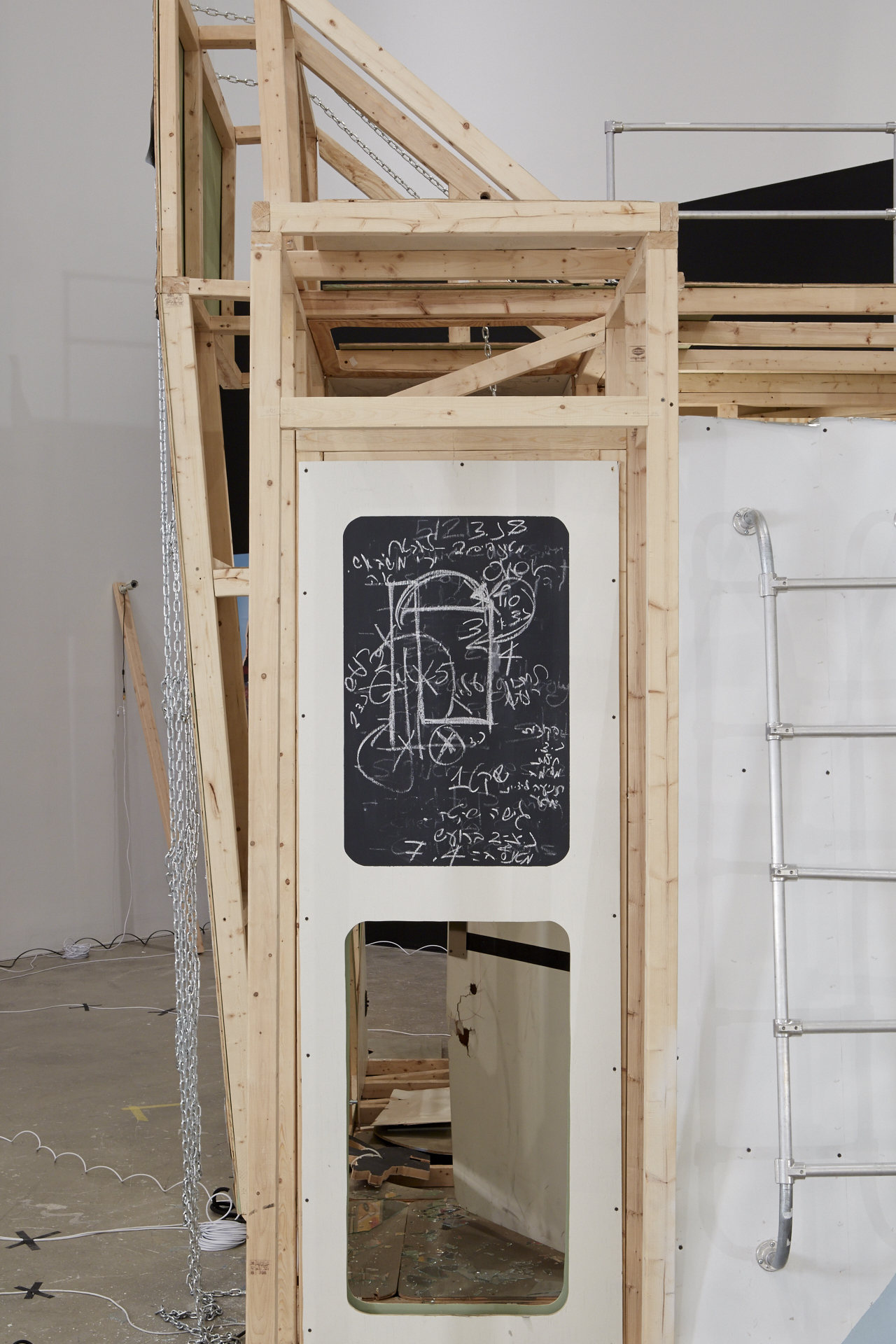

The phenomenal Ruffneck Constructivists exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Pennsylvania (curated by Kara Walker) is exemplary in capturing the nuances of the contemporary art world’s hip hop turn, and what critical engagements with the genre’s aesthetics can generate. Featuring video artist Kahlil Joseph, most famous for his collaboration on the Flying Lotus music video for Until the Quiet Comes, legendary performance artist Pope.L and South African Dineo Seshee Bopape, known for her ability to build mystical micro-universes in poetically messy installations, the exhibition explores the constructivist tendencies of hip hop and marginalised urban culture, asking how “resistant bodies who reshape space” may contribute to the way we make worlds.1 Until the Quiet Comes, Joseph’s cinematic masterpiece, arrests time at moments when black bodies are embroiled in scenes of violence: A pre-teen falls to the ground in an empty swimming pool and a long shot pans over the dramatic sweep of his blood, tracing the curves of the pool. A man, seemingly immobile and likely dead on the ground, picks himself up in what appears as reverse motion, and subsequently transforms into a tenderly figure dancing through the people and the world around him. He moves, while they do not, and the space is moulded by his gestures, not the other way around. Joseph produces a new relationship between the black body and the three-dimensional world, embedding this choreographic relationship within “the troubles,” to borrow the expression from Donna Haraway.2 In the exhibition’s curatorial statement, Walker ingeniously identifies something distinctly Futurist in the proposal not to flee from catastrophe, but to act from within it, situating hip hop culture within a genealogy of twentieth century war-time avant-garde. The nihilistic streak that runs through the exhibition also serves as a counterpoint to the art world’s almost three-decade long obsession with work that actively intervenes in social relations, an impulse that evolved from relational aesthetics into socially engaged art practice, and which, particularly post-2008 economic crash, is at the forefront of conversations on the role of art in society at large. While figures such as Suzanne Lacy and Paul Chan have gained recognition for their large-scale “infrastructural aesthetics” that strive to produce social good, other artists like Santiago Sierra and Thomas Hirschorn have been more invested in producing antagonism in their work.3 The art world ostensibly continues to search for an authentic avant-garde, and it is within this landscape that a growing number of artists, critics and curators are now looking to the aesthetics of hip hop to understand how form can not only inspire but help construct new social realities. Walker deftly shines a light on the way hip hop culture’s aesthetics have the potential to disrupt social norms; not merely aesthetics for easy consumption, but carving spaces for discomfort within the world. Discomfort and malaise are at the heart of Walker’s own art practice, and with Ruffneck Constructivists, she deliberately challenges the artifice within the art world’s trendy engagement with hip hop culture, as well as the danger of appropriation by an art world that remains predominantly white and male-run.4

Away from North America and Europe the case of Senegal, a former French colony perched on the western-most point of Africa, is useful for understanding alternative ways of engaging with, and participating in the hip hop turn. If the counter-cultural claims of hip hop are to be truly mobilised, reflection must expand to other spaces where this culture gains momentum, else we risk missing the enormous potential of hip hop as an organic manifestation of the avant-garde. For the last three decades in Senegal, hip hop has, and remains a widely popular music style, distinct from genres such as mbalax that are closely associated with perpetuating culturally embedded values and traditions. Amidst a landscape steeped in cultural conservatism, hip hop’s rise to prominence in Senegal is worthy of investigation, most significantly because of the way it has shaped the horizon of both the country’s imaginary and its political reality. The constructivist tendencies of hip hop’s creative praxis, its ability to wed cultural production and world-building with an antagonistic edge is particularly striking in Senegal.

Youssou Ndour is Senegal’s most famous mbalax musician and the video to "Serin Fallu" is an example of how mbalax aesthetics often reinforce cultural norms and hierarchies in Senegalese society.

P.D.S. stands for the Parti Démocratique Sénégalais who in 1991 formed a national unity government with the ruling Parti Socialiste.

Since its beginnings, Senegalese hip hop has been overtly political and constructivist in its form and claims. The genre took off in the second half of the 1980s, propelled by the country’s serious social and political crisis that was born of structural adjustment programmes and a drastic reduction in state services for the general public. 1988 saw the country’s first année blanche, where the academic year was invalidated following a host of strikes that brought the University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar to a standstill, as well as the nation’s high schools. During this period, rap group Positive Black Soul rose to prominence; the lynchpin of their message being the creation of an alternative path for political engagement through hip hop. One line from their early songs, “Dioko”, is revealing in this sense “We are not the PDS, not the democrats, we are the PBS, a new party”. Simultaneously, Set Setal, a vast movement of re-appropriating public space was spreading throughout Dakar, as rappers, artists and young people used their creativity to improve the physical and mental conditions of their environment where the state had retreated. Images of local heroes began appearing on walls across the city, neighbourhood clean-ups became increasingly popular, and frequent up-and-coming rappers collaborated with ASCs (Associations Sportives et Culturelles) to organise open mic gatherings.

One critique levelled at socially engaged art practice from Claire Bishop is that it too easily picks up the baton of the state’s responsibilities, uncritically and operationally contributing to the enforcement of a neo-liberal system, however unintended.5 In Senegal, the social mise-en-scène produced by hip hop has remained extremely critical of the state, considering their position as offering alternatives, while holding government to account at the same time. This has never been so pronounced as in the early 2010s when the movement Y’en a Marre [Fed up], initiated by a group of rappers and journalists, used mass cultural and social mobilisation to ensure democracy was upheld during the polemic presidential elections of 2012. The influence of hip hop came to be decisive in the results of the electoral process, wherein sitting President Abdoulaye Wade lost to Macky Sall. The movement’s protagonists used aesthetics and symbolism in ways that were comparable to some of the most well-known pieces of socially engaged art practice. On the March 19, 2011, on the anniversary of Senegal’s first change in political regime, Y’en a Marre organised a peaceful demonstration at the city’s Place de l’Obelisque. Beyond the symbolism of the date, the participants were asked to tidy the square in a collective act of cleansing. The consequences of this act have been far-reaching, having inspired the ‘Balai Citoyen’ movement in Burkina Faso that, in 2014, ultimately forced President Blaise Campaoré from power. Viewed through this prism, a rapper such as Fou Malade who was instrumental in Y’en a Marre wields arguably as much influence on a national scale as Kanye West, but is an actor in initiating social change through form, rather than affirming commodity culture, highlighting the scope of hip hop’s potency.

Such examples demonstrate the necessity to look towards initiatives such as Ruffneck Constructivists that strive to unpack the power and complexities of hip hop culture, and who are notably not merely using this force for market or reputational gain. In this sense, the work of RAW Material Company in Dakar is a useful example to consider, as a site of enquiry into expanded artistic practice and its relation to society that categorically rejects any binary distinction between “high” and “low” culture. RAW’s position in Senegal and its engagement with work produced on the African continent, has allowed it to focus on narratives that are often overshadowed by the cultural hegemony of the U.S.-Europe alliance, a valuable position through which to investigate the global significance of hip hop culture. There exists a wealth of scholarship on Senegalese hip hop that is highly informative and insightful, yet remains largely oriented towards sociological and anthropological fields of study. RAW Material Company, rather, has been prescient in creating platforms for thinking about hip hop as an artistic avant-garde, doing so in collaboration with Keyti and Xuman, two Senegalese rappers who, in 2013, created the Journal Rappé. Journal Rappé is a news show rapped in Wolof and French that has not only paved the way for a greater democratisation of information sharing in the country, but has also affirmed a new aesthetic in knowledge creation by mixing news-room snippets with rap and satire. This platform took shape during a RAW Académie session over a seven-week period in late 2017, bringing together a range of both young and experienced practitioners. The central motivation for the creation of the Académie concerns the ongoing need to focus on alternative pedagogies. For instance, one of the main thrusts of the “Five Elements…” programme was to deploy music as a method for learning. Aided by a host of exceptional faculty members, including scholar Ibrahima Wane, academic and artist Ayesha Hameed, as well as filmmaker and author Fatou Kandé Senghor, hip hop culture was rigorously engaged with as a site for the creation of knowledge, divorced from high / low dichotomies of conventional cultural production. Koyo Kouoh, founding artistic director of RAW Material Company, has consistently argued for, and acted upon, the need to theorise from within the African continent. According to her, without this theorisation, African creative practice will be perpetually forgotten, misunderstood or overshadowed. If the hip hop turn we see active today can be read as part of a quest to fulfil the art world’s attachment to the avant-garde, the Académie programme offers new material standpoints from which to disturb the contours of canonized art history that continue to uphold only a particular narrative of the avant-garde. By extension, it also opens the potential of the hip hop turn for social change, using Senegalese hip hop’s world-building model as a necessary and pertinent alternative to the world-confirming of Kanye West at the Fondation Louis Vuitton.

Jenny Mbaye, a faculty member of the Five Elements program, speaks of hip hop in terms of an “aesthetics with cognitive value”. In Senegal, hip hop is undeniably an aesthetics with great social value too. It is this value that the contemporary art world seems to be drawn to, a legitimising force for art’s role in society and potent bridging vehicle that echoes aspirations from much twentieth century avant-gardism, beginning with Dada and Futurism. Certain cases, however, point to the institutional embracing of hip hop as little more than an attempt to appropriate the genre’s constructivist success and its demographic reach. An art foundation such as Louis Vuitton whose wealth comes from luxury goods, and who showcases the work of Kanye West while engaging in no public self-criticism as to their own implications in upholding a flagrant class system and the perpetuation of the eponymous LV trademark as a marker of wealth and power, is hardly unproblematic. Such an example points to the danger of hip hop culture’s co-optation by stakeholders who continue to reinforce systemic sexisms and and racisms subtending both the art world and beyond. The Ruffneck Constructivists exhibition, on the other hand, engages with hip hop’s aesthetic interventions and disruptions of the dominant symbolic order in a powerful exploration of hip hop’s relation to the social and political that does more than absorb the genre’s cultural currency. The “Five Elements” Académie programme functions in a similar vein, providing a platform for bringing to light the transformative potential of hip hop on both local and national levels, and using it as material to enquire into non-Western modes of avant-gardism, a coherent mission when viewed alongside RAW Material Company’s work over the last seven years in Dakar. “Five Elements” provides us with the opportunity to embrace hip hop as part of a lineage of avant-garde practices within art history, and serves as a fruitful reference point for an art world that attempts to navigate its role in societies under increasing social, political and climactic pressure. A celebration of the truly transformative power of hip hop culture that embraces interdisciplinarity and its multiple “elements” is also a demand to look beyond gallery walls when searching for the avant-garde.