In an ecosystem of expectations, memes cash in on the primeval instincts that both sustain and continuously undercut the order of common sense that determines their place.

Memes operate at the low end of cultural production, they freely circulate with and as trends, proliferating with seemingly no defined formula. These relatively instantaneous media objects are swiftly copied, remixed and embedded into web pages, having become the de facto visual culture of the internet. The language of meme production, as any designer will tell you, has little to do with visual design but how ‘sticky’ the concept is, its ability to evoke an immediate response with viewers, intended or otherwise. In the preemptively titled, Can Jokes Bring Down Governments?1 Dutch design collective Metahaven consider memes as cultural weapons that, if infectious enough, could snowball into unifying grass-roots movements with significant political consequences. Published in the wake of the Arab Spring, the book signals the politicization of memes and humor online, examining the platform infrastructure from Twitter to 4chan that facilitated the sharpening of memetic culture into a political weapon. It wasn’t until the election of Donald Trump in November 2016 that the potential for meme culture in organising networked communities that could disrupt established political norms, re-entered critical academic discussion. Since then, extensive research has been carried out in analysing the role of memes in shaping the collective ideology of the alt right, and how their circulation was woven into the American conservative movement.2 Without seeking to measure the impact memes had in the cultural war for the White House, it should, in the least, be acknowledged that the production and circulation of memes contributed significantly to unifying once patchy nodes of conservative far right views in the run up to the 2016 US election. Additionally, much of this meme culture operated through a process of collective, primarily anonymous, remixing of visual imagery via message boards and social media channels.

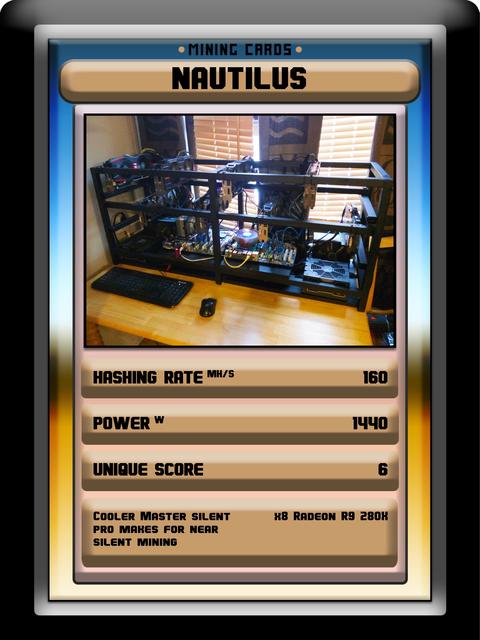

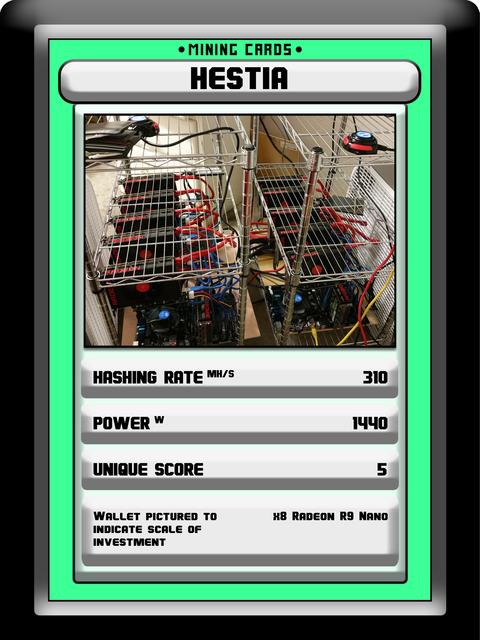

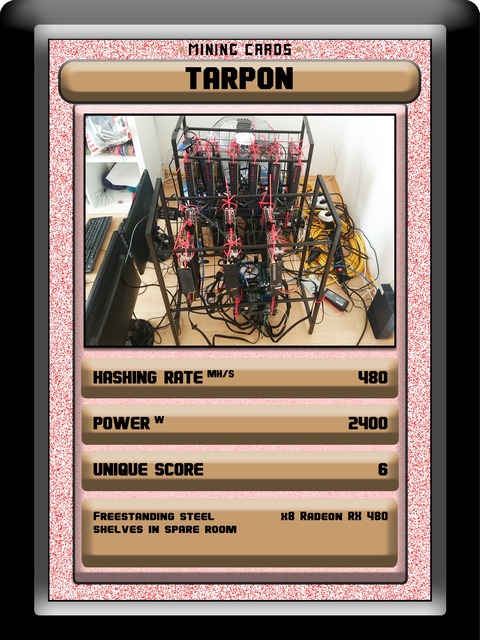

During the 2016 election cycle, in a neighboring sub-channel, memes were flooding into the cryptomarkets as the price of Bitcoin went from $13 US at the beginning of 2013 to $18,000 US at the end of 2017.3 During this period thousands of similar currencies were launched as market capitalization soared and individuals poured money into alternative currencies (alt-coins) to collectively speculate and trade on the price of crypto-currencies against the financial markets. The popularity of crypto-currency trading (commonly referred to as day-trading) escalated, and dedicated platforms such as Reddit, Twitter and Facebook groups became the breeding ground for memes specific to crypto-culture, known as ‘crypto memes’. DogeCoin, based on the shiba inu ‘doge’ internet meme, is by far the most notorious meme currency. Amongst a flood of alt-coins attempting to capitalize on the cryptomarket inflation, the doge subverted common expectation by becoming a complimentary currency for tipping small amounts of doge to users on Reddit, and through a bizarre display of commitment to the joke, was valued (at one point) at over $2 billion US dollars.4 Originally invented to parody the bonanza of alternative currencies that were being released at the time, DogeCoin is the most significant example of what can happen when memes are deployed within the theatre of cryptomarkets. Parody projects similar to DogeCoin have become prevalent in crypto, since unregulated cryptomarkets provide an environment well suited for pranksters to release scam-like joke currencies, fake token sales for conceptual companies, or financial instruments as satirical critique.5 The rules of the joke still apply to memes in crypto but the use of joke money or meme-as-currency indicates a significant trend towards emergent forms of currency art. Meme based currencies have led to a wider ‘movement’ of cultural branding for blockchain and cryptocurrency enthusiasts, that attempt to popularize crypto-trading through the exchange of meme currencies that are distributed and traded like limited edition collectable artworks.

To understand how memes can be considered as artworks, it is useful to firstly examine the convergence of interests between cryptocurrency and art, as well as some of the technical attributes that enable the simulation of market scarcity for digital media. A multitude of platforms have emerged in recent years offering artists, designers and creators the opportunity to distribute limited editions of their content by cryptographically en-signing their digital artefacts into a blockchain ledger.6 This approach, as described in greater detail by Martin Zeilinger in ‘Digital Art as Monetised Graphics: Enforcing Intellectual Property On The Blockchain’7, is an attempt to commodify digital artefacts into fungible financial assets where the blockchain is used as a digital public ledger that can be used to authenticate creation, ownership and transactions of a digital work. Not only does this attempt to inject legal ownership rights (such as intellectual property) and authenticity back upon the work of art in the age of digital reproduction, but can be seen as a broader indexing of finance in culture and contemporary art, where the shrinking of public cultural funding and the restriction of art market sales force artists to explore alternative survival strategies to monetize their practice. An array of galleries, crypto-enthusiasts and artists responding to this issue are encouraging creatives to produce limited edition digital versions of their work, which they can then sell using crypto-currencies, and distribute using tokens or blockchain based contracts (known as smart contracts). ‘Crypto-Collectables’ are decorated financial tokens that are automatically tracked and sold via interactions with a smart contract on a blockchain. Crypto-punks, Crypto-kitties and Curio Cards all demonstrate this phenomenon, where visual images are encrypted and sold as virtual tokens that are traded as collectable digital assets, and where financial trading is also performed with Pokemon-like collectable cards. While advocates for crypto-art promote the de-centralized storage system of blockchain architecture and the unregulated economy as an enabler for creatives and artists to produce diverse modes of creative expression, the original and most prevalent example of crypto-art is currently a collection of pepe the frog cards called ‘Rare Pepes’. A fanatical trend of producing thousands of remixed illustrations of the infamous Pepe the Frog meme, cryptographically registered to appear artificially scarce, sold, traded and collected with ‘Pepe cash’ – a dedicated cryptocurrency for the trading and collecting of rare digital Pepes. At the first ‘Rare Digital Art’ auction that took place in January 2018, a number of fine art auction houses witnessed a Pepe the frog meme sold for $30,000 US under the premise of it being a work of ‘rare digital art’.8 Whilst some members of the community have publicly attempted to disavow associations between rare Pepes and the alt-right, the hyper-trading of rare Pepes based on fractionalized ownership and market sales signify an extreme endorsement of free market principles traditionally associated with the conservative right. While the argument could be made that Rare Pepe creation is a counter-strategy to disarm the neo-fascist affiliations of the appropriated comic book illustration, this could be done without financializing digital images into collectable artwork assets. The use of blockchain to create originals, editions and inject scarcity into the circulation of digital media contradicts the structural properties of conventional web protocols and meme culture that thrive on the copyleft remix culture of the early web. Researcher Matt Goerzen briefly pointed to this contention in his essay ‘Notes Toward the Memes of Production’9 where he asks how the alt-right were able to extensively benefit from the copyleft culture of the web. In addition, the rare memes commodify the collective process of producing memes, turning what was usually an anonymous or collaborative practice, into an authored artwork with which the artist or designer uses blockchain to substantiate ownership claims and profit from crypto-speculation.

We’re going to help thousands of artists get their first crypto not by signing up for an exchange, but rather by selling their art.

The R.A.R.E Digital Art network attempts to use blockchain not only to implement intellectual property to re-create artificial scarcity for digital content, but also to build token-based schemes to further divide and fractionalize ownership of digital information. In turning digital bits into authenticated and versioned editions of files, financial value is not only asserted through the use of a cryptographic ledger but is also determined by the popularity of the file. In what appears to be a crystallisation of these aspects, the term ‘meme-economics’ is frequently used to describe these nascent meme currency cultural practices. The meme economy10 is a platform for the creation and trading of meme currencies, where individuals produce memes and sell token shares in their memes that are continually floated against other coins in the cryptomarket. A truly liquid form of creative production. Web analytics is used as a metric indicator to evaluate the financial value of this form of cultural expression, the creation, circulation and collection of these artefacts are continually in flux with market prices to produce what Richard Dawkins, the coiner of the term ‘meme’, might call cultural survivalism.

If we continue to consider the relevance of memes to contemporary artists and designers, it is necessary to reframe the analysis and ask how much creative labour is already being subjected to meme-economics. Promoting oneself with original content or producing culture that is likeable, shareable or Instagrammable are now strategies of artists and advertisers alike. Due to the mass capturing of audiences through the platform monopolization of the web, the artist (and their work) must become a successful meme, or operate in a meme-like way in order to survive. If one is prepared to acknowledge these conditions for contemporary artists (the consistent compromise of giving away free content in exchange for data-extraction) through their use of web and networked media, then turning one’s practice into a meme-based asset vehicle in order to survive might not be as ridiculous as it sounds. At least perhaps not to Hito Steyerl, who in her recent collection of essays in Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War11 hits out at the surrendering of artworks to collection houses and the trading of art as an investment vehicle for the ultra-rich. In the chapter “If You Don’t have Bread, Eat Art! Contemporary Art and Derivative Fascisms” Steyerl highlights some of the similarities between crypto-currencies and art markets. Both survive on collective belief (aka hype) around the artist (or the coin) and double up as a proxy asset for storing wealth and facilitating financial speculation. Steyerl’s analysis illustrates the entangled romance between art and crypto-currencies, and posits an intriguing question – while culture is promoted and disseminated through free online economies and fine art is bought only to be privately housed and to accumulate value for the ultra-wealthy, can artists respond to these conditions and design bold initiatives for financially independent models of cultural production?

As an alternative currency, Art seems to fulfil what ether and bitcoin have hitherto only promised.

While the majority of examples listed so far have limited the use of blockchain to simply reinforce property law and simulate market scarcity, there are a handful of artists exploring how the financial tools could offer more progressive long-term approaches to finance their creative production. The artist Rob Myers describes some of these approaches in the article “Tokenization and its Discontents”12. In the article, Myers describes the tokenization of digital art as ‘quasiproperty’, a useful term to describe the implicit contradictions of never being able to ‘own’ a digital file, but, via blockchain hash encryption, one is able to offer derivative ownership of a file through the sale of limited tokens that represent it. The extension of immateriality in the financialization of the media artwork exceeds property based ownership when net-artist Rafeal Rozendaal13 wrote a contract that enable artworks to be sold under the transfer of ownership of website domains. Myers goes on to suggest that tokens could be used as a form of patronage to give sustained financial support to artists or artworks. An example of this is the artist Jonas Lund who has released an official token (The Jonas Lund Token, 2018) that uses blockchain to turn his artistic practice into a shareholding company, where each token issued gives voting rights on upcoming decisions to shareholders. This demonstrates the use of cryptographic tokens to formalize a sustained group of investors in an individual’s practice and financializes the artist’s practice as a share holding company (where Lund is the CEO).

There are a handful of similar artistic experiments in using cryptography and currencies to issue tokens and shares in artworks. The most progressive interpretations of these developments is provided by researcher Laura Lotti who, in her article ‘Financialization As a Medium: Speculative Notes on Post Blockchain Art’14, asserts the need for artists and creatives to work through such developments. Lotti makes the case for using blockchain technology to enable greater autonomy of one’s creativity work, in the sense of self-sovereignty, when an artwork is issued through its own currency and ownership, when the distribution rights can be written by the artist and implemented by blockchain technology. Frequently such experimentations are dismissed by cultural philosophers and are criticized for further accelerating or even affirming financial capitalism. Lotti, however, defends the case for greater artistic autonomy through the creation of blockchain based organisation models for financial independence:

In so doing, they provide a glimpse of a post-blockchain future perhaps not too far away, in which tokenization, and the new affordances it provides in terms of self-issuance and self-utlilization, becomes the condition for arts autonomy through automated smart contracts.

Screen Shot from Jonas Lund Token (JLT) website.

Both Myers and Lotti’s case for greater artistic autonomy through tokenized asset distribution are based upon acknowledging the economic conditions of cultural production of web 2.0. platforms, and further admitting the extent of which finance already influences the contemporary art market. The lure of illusive money in the art market is often what propels artists into continuous state of precariousness alongside the necessary imperatives to constantly market your practice on social media or crowdfunding platforms to sustain creative ambitions. The support of avid, radical artistic experimentation with imminent financial territories should be widely supported, for the very least to avoid limiting the imaginary potential of digital art to reproducing market scarcity and collectable Pepe the frog memes. Artists can bring much more explorative visions to this field, rather than reducing the possibilities offered by blockchain to personal meme collection. Artists can shape these emerging experimental financial tools to better serve the arts and culture more broadly, rather than letting the possibilities for alternative financial models become over-determined by cryptomarket culture.