It looks like the end might be beginning for the European Union as we know it. If in the centre the European Social Model still holds, on the fringes of the federation its social, cultural, political and ecological failure shines bright. Two years after Brexit – the first case of secession in the Union’s history – with the Russian-Ukranian war destabilising its Eastern borders, with 95 million people at risk of poverty or social exclusion (20% of the EU population) according to the Union’s own official sources1 and neofascism on the rise, the prospects are dark.

As the Union loses support and its institutions weaken, citizens are left gasping for air—literally, if you live in Northern Italy like we do, one of the most polluted areas in the Union, but also figuratively: we look for a sense of comfort, for a glimpse of that capitalist dream we’ve been sold so long ago. That everything will be alright.

But it’s never alright, is it? You did everything right: school, job, you’re even self-branding on social media. But you can feel the world around you collapsing, the nothingness at the core of capitalism swallowing its façade like a pothole on a movie set. How can we avoid getting crushed by the debris? How do we fill that empty space with prosperity, creativity and joy? Is there room for us to play among the rubble?

Milan lies at the border between the functioning continental core of the European Union—what the geographers have called the blue banana—and its collapsing Mediterranean fringe—what the Union’s bureaucrats, not holding back on their Nordic racism, have called P.I.G.S.

The neoliberalism of the EU worked (partially) well for some provinces in the Northern core of Europe, but for Italy and other peripheral countries it was a disaster. With a corrupt ruling class, the welfare state was dismantled, both industry and agriculture collapsed under the double pressure of the more technologically/organisationally advanced competitors of the North and the cheaper options from outside the EU.

Embracing the “creative city” model, Milan feels like it escaped Italy’s fate. But, under its glossy, state-of-the-art, modern appearance, Milan is festering with infection too. The creative city eats people (marinated in their creative juices?) and shits profit. Profit is its only reason for existing. It’s a new extractive economic model based on land/property speculation and cultural (over-)consumption. That’s all the greedy system has left to survive after all industry has been outsourced.

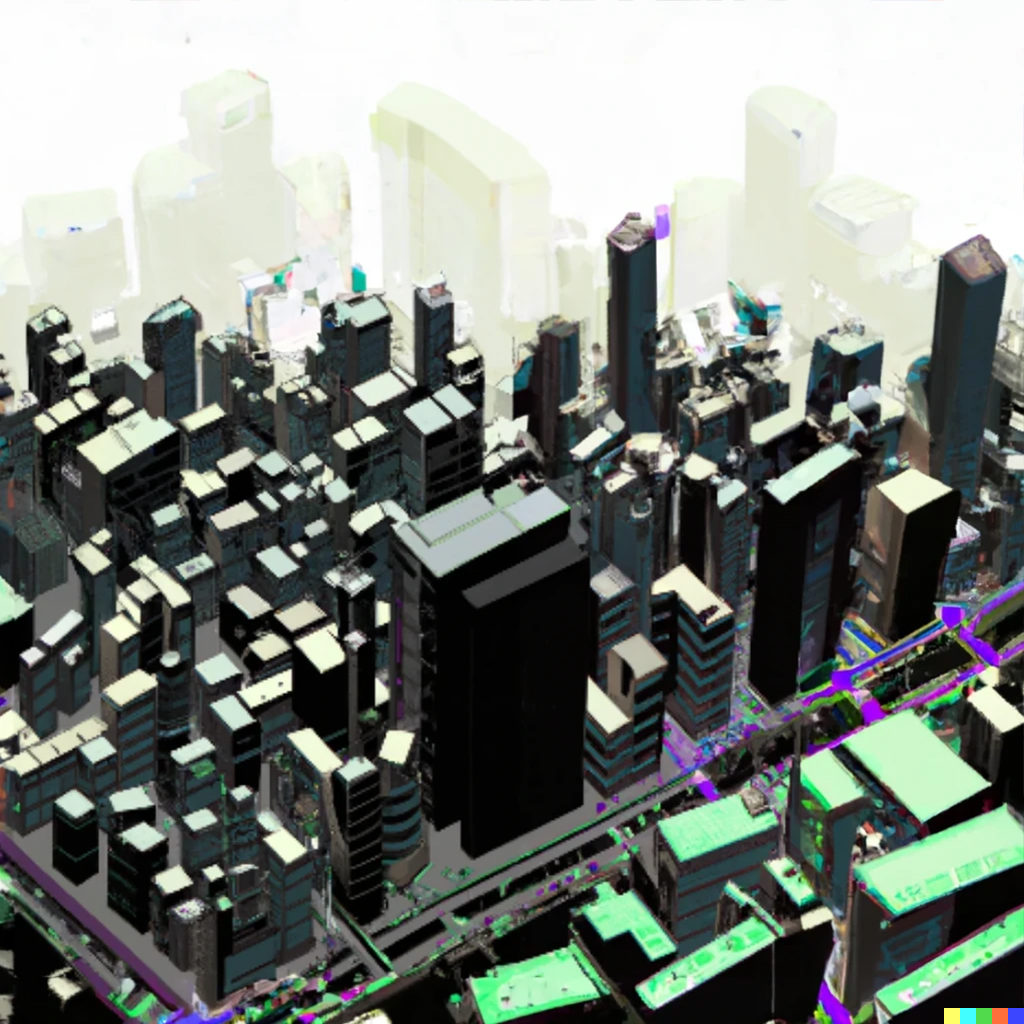

Milan is like an AI-generated picture of a thriving metropolis: at first glance, it looks fine. On closer inspection, though, you’ll notice it’s really fucked up. Socially the city is strongly divided between a wealthy elite and an impoverished service precariat. The average rent is higher than Copenhagen, Paris or Munich,2 yet the average salary — around €1900 after taxes — is half the salary of a Copenhagen resident (around €3700),3 while the municipality and the regional government are selling off public housing and reject any form of rent control.

Culturally, the COVID-19 lockdowns and the price hikes triggered by the Russian-Ukrainian war annihilated everything that wasn’t the mainstream. The logic is simple: the bigger, the stronger. A small underground venue, or a niche bookshop, or an experimental art space, can’t ask their patrons to help them weather the storm: they’re too few, and they’re too poor. These activities should be able to count on incentives from the government, but that would imply the government has an interest in keeping alternative culture alive — and it doesn’t. You know what ends up taking the place of alternative culture in a city like Milan? Brand-sponsored events, curated by cultured creatives trying to put their company’s money to good use — but unwillingly ending up cannibalising that same culture for a promotional stunt.

Despite the creative city rhetoric, wages in the creative sectors are particularly low on average, as employers take advantage of the endless supply of young aspiring creatives with little to no political consciousness — many of them supported by wealthy families — coming from all over the country and ready to work for nothing while waiting for things to be alright.

Hey, State, you’re saying you’re giving us welfare but to get welfare we need to enter a marketplace that eats away at our time, our self worth, our relationships, our mental health, and other people’s welfare in other parts of the world — ultimately, what kind of welfare is that?

In continental Europe, and in Italy in particular, we are lucky to have an oft forgotten, oft maligned as old and out of touch, but still alive and extremely important tradition of community self-organisation, or, as we call it in Italy, autogestione. Put simply, pick up what the neoliberal machine leaves behind, and use it as a community to self-produce that welfare. It does not always work. But when it does, it’s magic: from individual misery to communal luxury in the blink of an eye.

Our cities have a wealth of incredibly sophisticated yet unused tools and materials just lying around. Empty buildings with working heating, water and sanitation systems, mountains of discarded construction materials of every kind, a never-ending amount of second-hand electronics which are perfectly functional or can be restored quickly, trucks of old furniture getting destroyed every day, tons of perfectly edible food which gets wasted for stupid reasons.

Squatted public spaces have always had a huge part in Milan’s cultural (and, obviously, political) landscape: Nobel prize winner Dario Fo changed the face of Italian theatre from the Palazzina Liberty Occupata; the Virus squat shaped the sound, attitude and aesthetic of punks in the Eighties; the Leoncavallo squat was a hub for the anti-prohibition movement and the anti-globalization movement in the Nineties, and we could go on. But one aspect that often goes overlooked when talking about centri sociali occupati autogestiti, meaning community-run squatted social centres, is their role as an alternative to the capitalist model in people’s daily life.

The range of self-managed projects you can find in a city like Milan is impressive: medical centres, sport clubs, practice spaces, art spaces, bicycles repair workshops, woodworking shops, soup kitchens, online platforms, after school services, housing projects, farmer’s markets, language classes… The list goes on. These are not alternative venues for shows and cultural activities: these are alternative forms of life.

Now one might ask, why squat when you can start a non-profit? And we’ll answer with a bit of wall wisdom, a phrase you’ll find spray-painted all over town: lawfulness is a rich person’s sport. The sort of freedom autogestione grants to the people who practice it can’t depend on funding, relationships with the authorities and all that stuff. No bosses, no budgets, no chain of command. The projects are run through an open assembly and the activities and services are free or as cheap as they can be.

To build and participate in this kind of activity can be hard. Political disagreements, technical difficulties, fights, crises, repression from the State—everything falls on the back of your community and has to be dealt with as a group. But how rewarding and full of pleasure life can be when you build these alternatives and you actually get to savour some time away from the self-mutilating machine of the capitalist city.

One would think, being a creature of the 1970s, that self-managed community spaces would be obsolete in the 2020s. But they’re actually way more important today. While in the past decades the Italian government still deployed a stronger welfare state, social centres and other community spaces had more of a fringe appeal and were home to individuals who had very specific political and social views. Today, this network of decommodified activities increasingly becomes the main—if not the only—way to enjoy things that otherwise would be inaccessible for the precariat. A social centre isn’t just the home of the anarchists, of the punks and the outcasts anymore—it’s a place where individuals and families go to get the welfare they can’t afford.

We all know this too well: there is no material scarcity in the West. On the contrary, we already live in tremendous luxury, but we are not allowed to enjoy it communally and use it as a base for individual and collective expression. Happiness, or at least a form of serenity, can be found even on the outskirts of a dying empire: it lies in collective creation, solidarity and friendship. The system designed by the ruling class, though, would rather we went after the dopamine hit of a social media interaction, of a canned laughter from a video or a podcast, of an online purchase—happiness in the age of its technological reproducibility.

If decommodified spaces are so essential for creative expression and social development as neoliberalism unfolds, how can more people be put in the position of engaging in communal luxury? The answer may vary a lot in relation to place and politics. In a city like Milan we see two things as crucial.

Number one: reclaim your time from waged employment. If we are stuck in a full-time job we will never have the time and energy to work for the community. If there are little incentives to work longer hours in a labour market where low wages are structural and depressed by inflation, many part-time jobs are enough to survive if we take on a more frugal lifestyle. And in our free time we can co-create and co-access things we would never be able to access if we had to pay for it.

Number two: reclaim social spaces. Independent culture in an economically declining country cannot survive on the market. Sometimes it is possible to access cheap social spaces via a benevolent local state that provides them or facilitates the use of private unused spaces. That’s good, and if you live in such a place you should work so that these places thrive. But don’t forget the little motto about the rich person’s sport: to squat empty buildings is still one of the greatest things we can do. It gives back the space to the community; it slows down speculation; it sends a message to the local authorities; and it frees you up to run the place truly as you, as a community, wish. Let’s face it: if continental European counterculture is any different from Anglo-Saxon counterculture is because of its relation to squats and former squats.

We don’t know what the future holds. But the social collapse and protests that happened in Athens in the context of the 2008 great recession, is now threatening the provincial capitals of less remote areas like Milan, Barcelona and Budapest. And this is not to preclude that it may soon also spread in the capitals at the core of the Union where—since the 2005 French riots, throughout the 2011 English riots and countless smaller events—we have witnessed continuous unrest among the new hybrid and multi-racial precariat of its suburbs. These radical forms of protest point to deep structural problems and show a growing demand for major social change that liberal politics do not want to consider.

Now, this is a piece about construction, not destruction. It’s about sharing with you the joy that we get from building something that other people can enjoy, and from enjoying what other people built, not for money, but just because we love each other as human beings. So let’s do it as much as we can.

Art by Francesco Goats