What is the relationship between jokes, dreams, empathy, politics and class consciousness? Jokes are often said to explore what is unsayable, a way to raise what we don’t talk about. In this sense, jokes are like dreams – jokes and dreams are both popularly assumed to reveal anxieties and desires, and these may be personal or political or both. This text argues that it is the empathic dissonance jokes foster that holds opportunity for progress and class consciousness. In essence jokes deliver a consciousness of differences, empathies; and it is this openness and sensitivity towards difference that is important for class consciousness. For the question of the class consciousness and political dreams, perhaps we should be joking about our dreams, our political hopes? Mightn’t the empathic dissonance and plurality that jokes deliver, in a chorus of laughter and conviviality, be part of an ethical and political practice towards class consciousness?

Before considering the role of empathy in jokes, let’s consider the differences and similarities of how jokes and dreams signify desires. Let’s turn to Freud. Smirk or laugh at the mention of Freud, but his name remains large for two of many reasons. Firstly, his work contains persuasive theorems for questions that have yet to be answered by the eliminative materialism of sciences. We don’t know why we dream what we dream, we just fuzzily know why we dream on a functional level (lack of R.E.M. sleep correlates with several physical and mental health issues including depression and psychosis). So, we know we need to dream, but what we still don’t know is why our dreams are like they are. An analogy: we know how a cinema projector works—light shines through a rolling film to a large screen etc.—but we don’t know why the images are of corridors, lips, vehicles, archives, horizons, forests, and various dread-steeped Acme-unconscious products. We need “content” (a frighteningly hollow and unspecific term) and understand the medium’s “mechanics;” but don’t know why the dream experience is what it is. Freud still offers compelling theories for this question.

Secondly, his work contains theorems that have since been nigh on evidenced and validated. For example, the central thesis of Mourning and Melancholia is strangely accurate when held up to recent findings in neuroscience: depression thought of as an implosion of energies not expelled/worked through. Robert Sapolsky, for example, touches on the similarity of Freud’s logic in Mourning and Melancholia to the neurochemical logic of depression and anxiety evidenced by advances in neuroscience.

Freud still offers arguments for the human condition that feel right and have yet to be dispelled by a materialist explanation or his work offers arguments that have since been proven to follow a broadly correct logic and set of presuppositions.

Neither of these diminish how problematic Freud’s work is, nor its nebulous complexities. In this sense, we are still working through our Freudian complex…the inflection here, that “a complex” is a “group of repressed or partly repressed emotionally significant ideas which cause psychic conflict” is apt for the many problems of Freud’s work and the damage they have wrought. Despite being radically progressive in terms of sexuality, it is difficult to make the case for the question of gender in Freud’s works.

The Interpretation of Dreams contains one of Freud’s famous insights: dreams express unconscious wishes, often related to childhood sexuality. However, dreams do not express wishes literally or directly. If this happened, it would mean the remembering dreamer’s unconscious is made conscious – and this would cause all sorts of discomfort and distress. A censorship (Zensur) occurs, “dream-work” is the unconscious masked in disguise expressing wishes in strange scenarios, bizarre events, riddles, homonyms, and jokes. For Freud, dreams are ‘insufferably witty’ because the direct path of the unconscious expressing its wish is barred. The masquerade of unconscious wishes in dreams can be interpreted by the psychoanalyst to reveal traumas, torsions, and tensions the unconscious is “processing” (to be cybernetic).

This thought is so intrinsic to psychoanalysis, and so much a part of popular culture, that it is difficult to imagine a world where dreams are not regarded as being significant in this way. Dreams have not moved out Freud’s shadow; dreams are still veiled cryptic expressions of unconscious wish. Registers of this in film and literature are numerous. The White Hotel by D.M. Thomas, the penumbral fantasies and dreams in 1982, Janine by Alasdair Gray, or films such as The Cell (Singh, 2000), all presuppose audiences know to interpret the significance of dream images like a psychoanalyst. One doesn’t need to read Freud (or even know his name) to think that a dream about flying has something to do with freedom, agency, liberation, empowerment, and so on. A large red train entering a long dark tunnel means something else…it is a typical wish fulfilment dream, a fantasy, of the Avanti West Coast passenger.

Jokes and their relation to the unconscious treads a very similar logic as Dreams. But it does so less convincingly. Jokes is one of the more dissonant and perplexing texts in Freud’s oeuvre, even for apostles. One of the awkward tenets of Jokes is the claim that witticisms (in waking life) partially reveal or signify the wishes of the unconscious. An important aspect of Dreams is that the significance of dreams is beyond the horizon of the dreamer/analysand. The significance of dreams needs to be interpreted by a psychanalyst. There is meaning in dreams, but this meaning cannot be reached by the dreamer without an other’s interpretative insight. In Jokes, Freud argues that the joker, in making witticisms, reveals a significance, or a connection, or an alternative meaning related to the unconscious. The immediate issue with this claim is that when one tells a joke, one knows the double meanings, the significances, all along and does not need a psychoanalyst to interpret these for them. Jokers are not like dreamers. Jokers, even before cracking their witticism, are fully conscious of the double meanings and alternative significances of their remark, whereas the dreamer emerges from sleep perplexed, troubled, and confused as to the meaning or significance of their dream.

Freudian slips—accidentally saying one thing when you mean a mother—are not at all like jokes. There is a double meaning, but the second meaning is not intended. It is a slip, an unintended accident; significance erupts autonomously from the speaker’s will or consciousness. Freudian slips are much closer to dreams than jokes: both are beyond the conscious control of the subject. “I don’t know why that came out” operates in the same vector as the confusingly vivid and specific recurring dream that will not go away. Both are beyond our consciousness control.

A second issue of Jokes is the centrality of wit, comedy, and humour in the unconscious. Wilhelm Fleiss observed that Freud’s patient’s dreams were full of jest and puns… suspiciously witty for a slumbering subject. The latter’s retort was that “all dreams are insufferably witty’’ (Carey, viii). Quite why Freud finds the humour of the unconscious so unbearable is another question for another day (Roudinesco’s superb biography might be a place to start though). Alas, Freud’s retort is hard to relate to. Dreams are strange, and full of plural meanings, double meanings, absurdity, the fantastic. Sure. But are they “witty,” are they funny? Dreams are involuntary like laughter, but that does not mean dreams are funny. When was the last time you woke, memories of the dream experience dimming crepuscularly, and felt a tickling giggle, a creeping smile, let alone compulsive laughter come on? For many, dreams are often not funny, but nonsensically absurd experiences peppered with vivid clichés. Are unconscious wishes, or our drives, funny? Not uncanny, or strange, but witty and funny? Would you invite your unconscious to dinner?… All that greed and lust amock, an open floodgate roaring with impulse, clotting fear and rotting anger, the soporific dread and anxiety, the capricious fantasies and stubborn fixations, the taboo breaking sociopathy. Mr. Blobby, on the precipice of a come down, trapped somewhere between a Perfume TV advertisement and a Gonzo porn shoot…The unconscious may be loud, strange, mercurial, and vivid… but humorously funny—witty—is doesn’t feel apt.

A key argument in Jokes is that laughter is brought about by jokes because of a pleasurable economy in expenditure. A short of short circuit that expresses something of the unconscious more directly, a loophole. Part of this argument is articulated around puns and double meanings (and very unfunny acts of misogyny). Throughout the text, Freud leans heavily on Theodor Lipps, and explores Einfühlung (empathy, coined by Lipps), in the context of jokes. Freud writes that ‘we take the producing person’s psychical state into consideration, put ourselves into it and try to understand it by comparing it with our own. It is these processes of empathy and comparison that result in the economy in expenditure which we discharge by laughing.’

“Discharge” may betray a scatological view of humour and laughter on Freud’s part (flashbacks to prime TV gunge pranks) but that aside, the observation of ‘dealing’ with two empathies resonates much more that most of the text fretting over wordplay and homophones. Consider a classic:

“My dog’s got no nose.”

“How does it smell?”

“Awful!”

If we read it as Freud/Lipps might, the joke pivots around empathic red herring. The joker tells the audience their dog is without nose. Interspecies empathising ensues, dogs lead richly olfactory lives. The canine-empathising audience ask “oh dear, how does the poor little pup get by? How does it live!?” The joker gives a response that is utterly selfish and incalcitrant to the experience of the dog: “it stinks.” The audience is wrenched from one object of empathy to another… the olfactory disabled dog is eclipsed by the owner’s offense at the dog’s odour, pivoting on ‘smell’ being offered as a verb and taken as a noun.

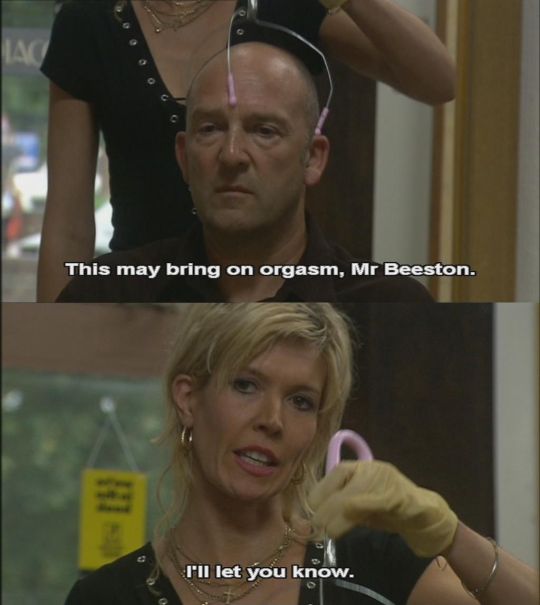

Empathic misdirection is the crux of many jokes. One example is hairdresser Jill Tyrell in Nighty Night (creator and writer Julia Davis stars as Jill). Jill is in her salon slowly massaging the scalp of a bald man with a metal apparatus. As we see the object stimulate the customer’s scalp, we hear her warn “some people say this can bring on an orgasm…” The man looks up at Jill—grey background foley fills a moment—and Jill adds softly, candidly: “…I’ll let you know.”

Of course, the joke subverts traditional views around gender and power on one level. On another level it is a “perfect” joke for Jill’s character. Jill Tyrell is an antisocial, deeply narcissistic and callous character. An empathic red-herring (the eclipse of the customer’s needs with Jill’s own) plays a similar role as the patinated dog-without-a-nose joke. But it also underscores just how utterly selfish and unemphatic Jill is. This is not a diegetic joke, there is no mirth in scene. Perhaps we laugh in this moment due misplacing our empathy, or having our empathy wrenched from one object to another? Of course—this is the sigh, the exhale, the economy of expenditure—Jill is referring to herself.

These types of empathic wrongfooting are common in jokes, funny or otherwise. A classic example, based on a xenophobic view of Italians, runs like this. Italian soldiers are ordered to attack by their commander. Nothing happens. The commander bellows again: “soldiers, attack!” Nothing. Last try: “Soldiers! Attack!” At which point a single soldier’s voice is heard saying “Che Bella Voce!.” Italians, so the logic of the joke goes, are opera lovers, not fighters, not men of action but men of aesthetic appreciation (Mladen Dolar explores this joke in greater detail in A Voice and Nothing More (2006)).

Many misogynistic, racist, and/or xenophobic jokes often take this structure. Introducing an assumption and an object of empathy, only to eclipse it with a dismissive, bigoted and hateful statement conveying about the view of the joker. Often these jokes play on an assumption only to override such assumption with the “butt” of the joke – in each case, there tends to be an active mis-empathising. We can see variants that frame the butt of the joke as a dominant group after playing on assumptions of a vulnerable group. E.g. A weatherworn man, conspicuously poor, with poor English, explains how far he’s travelled, the things he’s seen in his life. “I can’t imagine,” one offers. The man sighs and shakes his head at the ground: “Wolverhampton.” Or continuing Freud’s tendency to analyse jokes in terms of economy and money: a man asks a sex worker if he can pay on card. Sure, he is told, but there is a minimum charge. Absorbing this advance in commerce in an unrecognised industry he asks… “oh – and what do I get for that?” “It’s contactless.” The disjunct, the misdirection, here is the focus on the service eclipsed by the focus on the commerce – pivoting on the dual meaning of the term ‘contactless’. Freud would’ve liked this joke; he wouldn’t have laughed.

Explaining jokes is unfunny, and the above jokes are not funny to begin with. Nonetheless, why do jokes of such a structure persist? And why is this peculiar eclipse of misguided or “wrong” empathy (because often the initial object of empathy makes a lot of sense only to be obfuscated with a more extreme or absurd object of empathy) so often found at the punchline when autonomic laughter occurs?

Jokes, of these types, in this sense, reveal a plurality of empathy that is a persistent issue of the human condition. We empathise, but sometimes we empathise with the wrong object. Or we empathise myopically, too acutely (with an individual, a narrative), and struggle to scale empathy fairly and appropriately or ethically. Jokes are examples of how our empathies are easily duped, our views are often misguided and wrong. The joker’s punchline—introducing an object that eclipses the initial object of empathy—is QED of our empathic misguidedness, or fickleness.

The point—the pivot, the punchline—at which the virtues of empathy, and how we empathise, understand, think and value the world are demolished and replaced is a strange juncture at which to laugh. We are on the merry road to scepticism, if the initial object of empathy was misguided, then what about this bizarre new object? Perhaps, jokes unite us across our empathic islands, maybe there is conviviality across this parallax view, a shared humanity in being misguided, distanced, ostracised, and wrong. Perhaps difference is more ‘human’ than certainty and knowledge and that is why some jokes elicit an autonomic spasmodic vocalisation—like crying—like “haha” or “hehe?” Maybe we laugh when it feels funny? Or to reverse the phrase for misdirected empathy, when we’ve woken up to having funny feels?

In this sense can we ask if laughter emerging from a convivial eclipse of empathy, building a plurality of empathies, contributes on some level to class consciousness?

One of the existential threats to progress is singular flat truth and fact. Commentaries and narratives in popular media are increasingly reduced to computational definiteness – The Best, The First, 6 Things you must do, 5 Things we Learnt etc.. Good and Bad are increasingly offered when discussion, question, rumination and the important endeavour of articulation are more appropriate. See William Davies’ consideration of this existential threat of the information age in Higher Education. In the cyber-din of facts, categorical statements, truth and quantification, jokes offer an oasis of galvanising conviviality, a togetherness in a world where meanings are plural, chimerical, and dynamic: where empathic focus is questioned, explored, and not taken as a given.

Class consciousness requires listening, and almost a degree of scepticism about our assumptions. I say almost, because the phrase is too full of reticence and suspicion. Jokes and laughter celebrate the obliteration of fact and empathic certainty: plurality eliciting a chorus. Consciousness requires the communality of celebrating plurality, questioning and learning as practice not task. Notwithstanding the distinct psychoanalytic, semantic, epistemological, and empathic aspects of the joke, might it not also be an opportunity for an ethical and political practice?