This issue of Making and Breaking seeks to map out some of the dominant psychogeographies of the present. The Situationist Guy Debord defined psychogeography in 1955 as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals.”1 Another way of putting this is to say that psychogeography was conceived as that which happens when psychology and geography creatively collide.

To stage such creative collisions, the Letterist International (the precursory group to the Situationist International) developed what they called dérive, a method of drifting aimlessly through the urban landscape, registering the “patterns of emotive force-fields” that suffuse a city. Dérive is the artistic procedure that initially produces psychogeography; perhaps aimless in walking route, yet not without a certain methodological rigour. The Letterists and Situationists were fond of wandering the city as artistic strategy, a practice they inherited from a long line of predecessors reaching from the Surrealists back to Daniel Defoe.2 What the Situationists added to this was a revolutionary ambition that was political as much as it was aesthetic. As early as the 1950s, they recognised capital’s tendency to absorb the collective lifeworld into its quantitative homogeneity and understood the destructive potential this entails for a humane society. For them, psychogeography was an attempt to develop subversive forms of knowledge and experience that could contest the reductionism of capital, expressed in the formulations of post-war urban planning. It tried to delineate an experimental space-time where the rules of the game were undercut by radical play, where new ways of being could emerge, outside of the space-time of commodified banality.

Such a level of analytical clairvoyance and political ambition coming out of an artist movement is enormously inspiring in 2025, as we witness how Creative and Smart City policies have turned so much of today’s artistic and cultural production into decorative services that flank the progressive sell-out of our urban infrastructures to financial investors and digital corporations. What do the sheer number of retrospectives, revivals, and publications on the Situationist International and its potential legacy that have been released over the past few decades attest to if not an incredible longing for contemporary manifestations of such aesthetic resilience in and for our own time? Part of this might be melancholia but there is also a strong element in there of what the late Mark Fisher identified in his writing on “hauntology:” the refusal to give up on the desire for the future.3 At a time when it has become intellectually fashionable to celebrate the looming apocalypse as post- or transhuman payback, we urgently need to reinvigorate our desire for the future. In her brilliant The Beach Beneath the Street, McKenzie Wark talks about the Situationist’s attempt at “an exit from the 20th century.”4 It is obvious that we’ve not only missed the exit from the 20th century that the Situationists tried to open but we’ve also taken the wrong entrance into the 21st century. The rabbit-hole we’re tumbling down right now does give us Alice’s terrors and desperation, though without the imagination and wonderland at the end of the tunnel. This is why we agree with Wark when she writes that one could do worse than looking back at those who last tried to dig themselves out of that doomed trajectory of capital’s debilitating an-aesthesia.

It is in this vein that the contributions of this issue of Making and Breaking take up the question of psychogeography once again. Many of the approaches presented within it extend beyond the city and the physical environment, going into the virtual dimensions of digital socialities, social media infrastructures and their affects, exploring shifting sociopolitical grounds and socio-economic factors, identifying new forces of power and potential sources of emancipation. They often include and map out the psychosomatic effects of such expanded understandings of the environment, paying attention to dominant or well-worn feelings, emotions, and behavioural effects, as well as those emergent that might yet to be named.

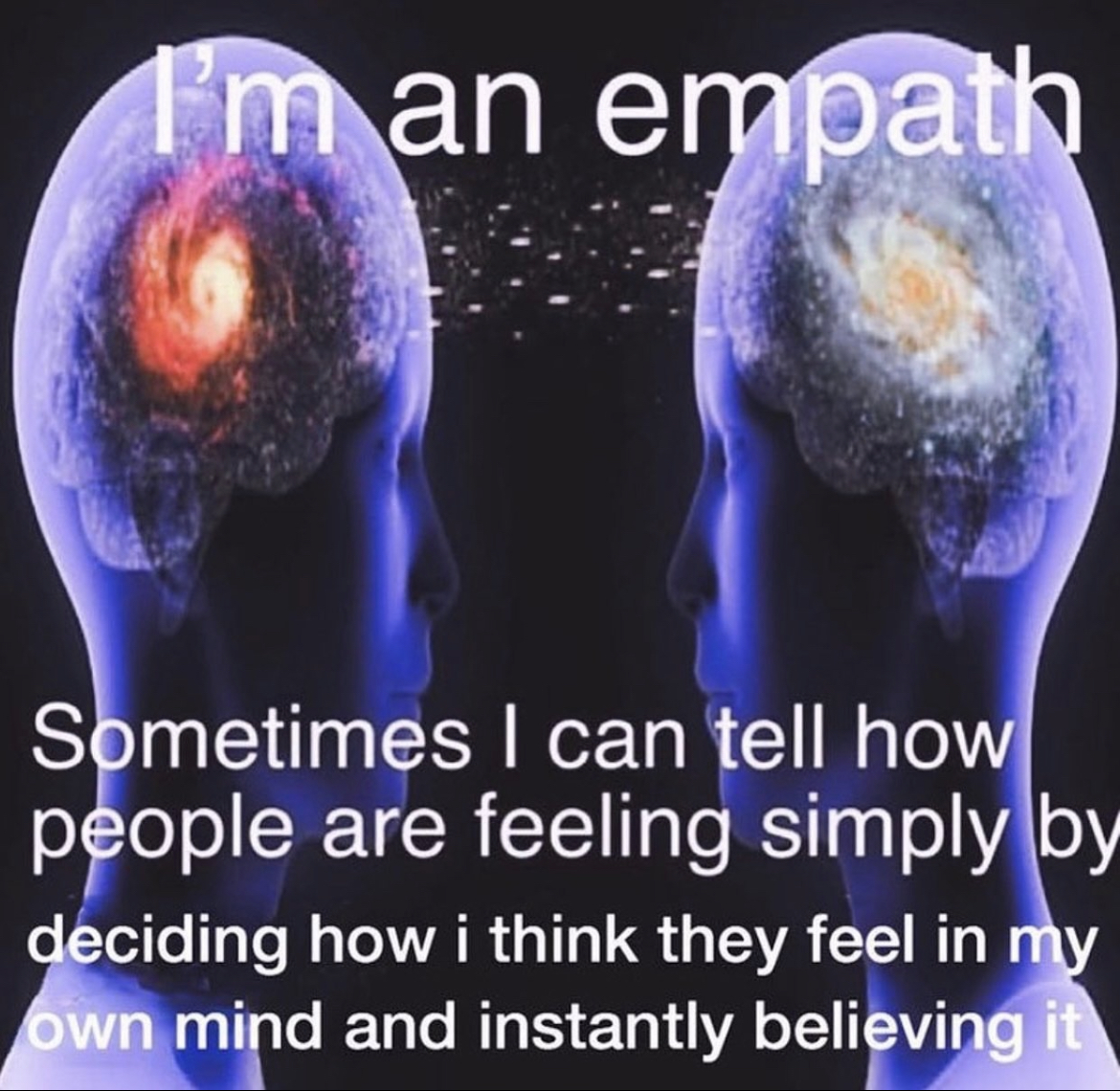

Digital media plays a crucial role in all of this. While we’re aware of the disastrous effects of social media on the psyche, particularly of the young,5 our online world tends to be pretty good at generating aesthetic means of communication that can be incredibly effective in expressing discomforts, disquiets, joys, or phenomena felt tacitly across the commons. The obvious example here being the meme. Sometimes a meme appears to perfectly illustrate an unnameable tingle of emotion or sociopolitical moment and is taken up en-masse speedily, with a sense of humour and urgency, or better: immediacy, than more elaborate and analytical (let alone academic) explanations seem to have the capacity to do.

Approaching digital phenomena such as memes psychogeographically necessarily involves the question of how to effectively politicise the psychological today. Politicising the psychological means engaging in a psychopolitics, which we intend here as the practice of placing ostensibly psychological phenomena and concerns within the register of the political and denoting the extent to which the human psyche is intimately linked to a host of structural forces, be they technological, political, economic, or simply historical. A psychogeography of our times must acknowledge the structural and environmental forces at play in producing these “specific effects… consciously organised or not, on emotions and behaviour.”

In letting our psychogeographical gaze intuitively roam across our present social landscape, we witness the rise of a culture fixated with self-diagnosis, self-care, self-development and optimisation, and the admiration of self-experience, as a strange iteration of hyper-individualism inherited from neoliberalism. While the individual psyche remains a crucial reference for any contemporary psychogeography, our understanding of it needs to heed the “therapeutic” groundwork laid out by the inventors of the dérive. To quote McKenzie Wark again:

“Psychogeography made the city subjective and at the same time drew subjectivity out of its individualistic shell. It is a therapy aimed not at the self but at the city itself.”6

What we need to understand is that today’s identitarian movements on the left and right resonate rather harmoniously with the extremist version of the self, produced by decades of neoliberalism. Deconstructing identitarian extremism in all its contemporary forms and conversions is the precondition for an emancipatory psychogeography; otherwise, its political impetus runs the risk of being reduced to notions of individual pathology.

The upside is that there is growing interest in the politics and (new) practices of community and collectivity. Artists increasingly engage with questions of care and interspecies relations, there is a desire for experiences of interconnectedness (via psychedelics, or otherwise), and a new generation is exploring forms of living and working that are less self-centred and more communal (luxury). What they share is a willingness to reach outwards in search of resonance with the greater world and breaking away from the heaviness that comes with dissecting, monitoring, and keeping constant awareness and analysis of one’s own (self-centring) identity.

It seems to us that the challenge for cultural production in our time lies in embracing a sense and practice of exciting, democratic togetherness against the revenge of undead iterations of neoliberal subjectivity. The fields of art and culture have been invaded by pop-psychology speech, disqualifying practices that are vital for its evolution – provocation, passionate debate, and indeed, judgement – as forms of violence. Yet, as Sarah Shulman reminds us, conflict is not abuse.7

The world of cultural production needs conflict, doesn’t it? Hence, if this issue of Making and Breaking engages with psychogeography, it is to raise some rather fundamental questions: Shouldn’t art and culture provide room for unbridled curiosity and possibilities? Isn’t this the space where play, fun, for ills (or silliness) happened, expressed through genres of conviviality, collective joy, absurdity, and humour? The place for speaking truths, fictitious or otherwise, in ways vivacious and carnivalesque, for taking a break, albeit how brief, from “the horror of existence” rather than being stuck in a constant mirror-state of seeing your Self, reflected back at… yourself? Our inkling is that approaching cultural production in psychogeographic terms might help identify what blockages are at play in constraining it to addressing what feels like only a handful of topics, in a handful of ways.

Our stroll through these Psychogeographies of the Present begins with Letizia Chiappini’s proposition of the notion of psycho-digital geography, examining how emerging virtual spaces—from TikTok to Uber Eats, and beyond—are transforming our understanding and experiences of physical urban spaces, social relations, and embodied experiences. From there, Max Haiven takes us into the heart of contemporary capitalism’s unwinnable game, laying out how financialised neoliberalism has gamified itself and, in effect, our lives, and how it incubates fascism. Next Dan McQuillan leads a tour through a psychogeography of AI, which will suck you into a visceral and fantastical—yet oh so real—storytelling walkthrough of the less-visible and less-voiced aspects of what this moment of artificial intelligence’s rapid development really entails, through its current darknesses with insight into where it’s heading.

In our interview with Liam Young, recorded whilst his locale of Los Angeles was ablaze, the speculative architect talks about his exhilarating attempts to stimulate our collective imagination in a way that does justice to the planetary nature and scale of our contemporary challenges. Another type of psychogeographic strategy is presented by !Mediengruppe Bitnik. In collaboration with Selena Savić and Gordan Savičić, they let us into their work on how the prevalence of rating functions amongst digital systems and platforms has led to online ratings, reviews, and comments shaping our perceptions and experiences of offline spaces and services, as accentuated in their exhibition 1 ⭐ Review Tour. We stay with artists and their new psychogeographical practices in the Image Acts duo’s reportage of how Steven Monteau and friends began building new psychographical tools by making cameras out of residual police ammunition they collected, left behind on the streets during the Gilets Jaunes (Yellow Vests) protests in France. The collective Experimental Jetset follows up with their The Drifting Library: Towards a New Biblio-Psychogeography, which meanders the streets of Amsterdam using its DIY outdoor little book exchanges as their guide through a ‘semiotic cityscape’, contemplating the possibility of a dialectical experience within the urban environment, and perhaps even a countering encounter of the notion that “print is dead.”

Our journey starts its exiting descent with a psychogeography of apocalyptic games by the collective Total Refusal, finishing with Tristam Adams’ drawing of a line between the importance of jokes and humour in and for cultural production, what the empathetic aspects of the joke might offer as opportunities for ethical and political practices, and where celebrations of plurality could go in enhancing class consciousness.

We thank you for joining us on this jaunt through Psychogeographies of the Present and continuing to support what Making and Breaking sets out to do. And thank you again to all our contributors for their valuable additions in the expansion of what a contemporary psychogeography could and can do – in all its possible practices, takes, developments, mappings, and applications.

With warm regards,

Your Editors