“Perhaps if human desire is said out loud, the urban planes, the prisons, the architectural mirrors will take off, as airplanes do. The black planes will take off into the night air and the night winds, sliding past and behind each other, zooming, turning and turning in the redness of the winds, living, never to return.”

― Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless (1989)

In our hyper-connected, late capitalist society, the concept of psychogeography needs to be expanded. Any thorough understanding of the psycho-topography of contemporary urban life requires the inclusion of the digital dimension. The approach presented here is inspired by Katie Acker’s unwavering dedication to exposing the sexist, racist, capitalist, father-fucking societal ego of her time, aiming to put it to work in our own. Yet, what would the purpose of such new, critical psychogeographies be? What practices would be relevant to consider? How can traditional objects of geography (bodies, cities, maps, retail) and digital infrastructures and spaces be explored? What are their interrelations and where do emotion and behaviour come in?

By way of a first approximation, one might say that the aim is to understand what kind of spectacle we are watching and how to resist it, and to do so by excavating the dirt and the cringe and putting them on display. A great example of doing this rather effectively can be found in Coralie Fargeat’s 2024 body-horror sci-fi movie The Substance . It explores the sheer terrors of identity, beauty and ageing within the context of Hollywood’s dream factory. Elisabeth, the film’s protagonist, lives in Los Angeles, a city synonymous with the entertainment industry and its emphasis on youth and beauty. The city shapes her life and self-perception: its pervasive beauty standards and ageism incite feelings of inadequacy, pushing her into a desperate attempt to hold on to her status of on-screen fitness beauty. In an eccentric twist of the film’s set-up, she herself is a crucial element within the urban media topography and the embodiment of what terrorises her (and everyone else) by constantly throwing up images of ridiculous social expectations. She becomes the strange nexus of psychogeography weaponised in the service of marketing, desiring the endless repetition of the most banal imaginaries of youth and beauty. The spatial setting and the psychological environment conspire to keep the spectacle of the body, identity, and actions in check. The vacuous TV studio, the decadent penthouse, and the ruined suburbia, in a continuum with a disfiguration of the female body represent an eerie version of psychogeography that is a key component of an updated version of the Situationist approach.

In Empire of the Senseless, Acker situates the narration in a present/near future city that is devastated by revolution and disease. First published in 1988 during the Reagan presidency, their brilliantly written apocalyptic tale speaks to us even more now than at the time of writing. It is up to us to follow the pattern it lays out and ask the political questions implied in the tale: How should we navigate the nowhere of the present, and where else is there to go in the realm of digital urbanism?1 How can users be brought out of a fixed place and into an alternative journey of discovery? The smart city paradigm and its techno-solutionist response to these questions have been but a mere attempt through gamification or apps, such as the rise of psychogeographical apps that offer digital versions of the famous dérive. This technique was originally deployed by the Situationists, mainly gravitating around Paris and London, to explore the urban space by following unexpected trajectories and routes. These apps function by turning the logic of navigation systems upside down: instead of bringing the user from A to B as quickly as possible, they deliberately create diversions. They are not designed to show any real-time traffic information, nor do they offer other widgets like finding restaurants and ATMs in proximity to the user. Detournement, another Situationist technique that means ‘rerouting or hijacking’ in French, was originally used to manipulate and transpose the images of marketing etc. into discordant contexts, trying to expose the inner workings of the spectacle’s objective reality.2 As a means of subversive political pranking through mimicry, repetition, and recontextualization, detournement could be said to have foreshadowed the phenomenon of memes, though certainly not the immediacy and viral temporality typical of social media platforms. However, the digital updates and phone apps of dérive and detournement are tantamount to how politically futile and toothless the original Situationist strategies were.3

@hrw789 via TikTok

Being a contemporary city dweller means being engaged in forms of agency, intimacy, and socio-spatial rituals that are mostly mediated using digital devices. They function as technological affordances that do much more than satisfy our desire for consumption, information, or participation, in all kinds of spectacular and mundane activities: their design choices and widgets are co-shaping these desires, manipulating processes of subjectification of the individual within a certain geographical and political space. By way of the smartphone, the society of the spectacle is now available to anyone, everywhere, all the time, at once. Take, for instance, the TikTok queues in front of the often breathtakingly mediocre food vendors throughout many cities. Masses of tourists stumble around the city with heads craned down over their screens as they walk like zombies towards the next attraction: an hour-long wait in the rain to get the extortionately-priced-but-viral vegan pistachio “cruffin,” waiting under an umbrella of the café’s logo. Whether it is a natural wine bar, TikTok’d bakery, or any other digitally marketed and memeable tourist-trap, these are manifestations of a hybrid spectacle that is initiated on the phone but has an immediate and direct effect on real urban space. Hybridity, immediacy, and viral effect are central features within the architecture, widgets, and affordances, of digital platforms that create hype by leveraging on-demand fever through their global-scale infrastructures. As result, consumption patterns are accelerated in random places or gentrification processes even more intensified.4 Affect, desire, pain, and love, are digitally mobilised for direct spatial impact. They are changing the topographies of our cities socially, economically, and politically. Tourists are lured in by the platforms and follow what the algorithms dictate to them in terms of the quantum of their food cravings. In the urban experience quest, are tourists individuals or insignificantly part of the global crowd on TikTok? These urban wanderers want to stand out by trying the ultimate urban experience and beg for visibility both in the city and on digital platforms. They are poles apart from the flâneur subject. The figure of the flâneur, conceptualised by Charles Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin, roams the city, allowing “the intelligentsia” to become “acquainted with the marketplace.”5 Moreover, Georg Simmel and other urban sociologists identified new characteristics like anonymity and a “blasé attitude” as essential to the psychology of the modern city.6 Yet, I would argue that this flâneur was always a bourgeois figure with a pronounced male gaze who had the privilege of being able to roam the city at their leisure (e.g., alone at night) in a state of near invisibility.7

There is no point in trying to fit critical feminism into the original concept of the masculine flâneur, though it should be clear that any attempt to put psychogeography to work in the present needs to move beyond the dandy. As a female body in the city, I never had the privilege of a complete sense of anonymity or a degree of invisibility. Leslie Kern, in the book Feminist City (2022) makes this point marvellously, referring to the “constant anticipation of harassment [which] meant that any ability to glide along as one of the crowd was always fleeting.”8 Such systematic (though, of course, not absolute) exclusion of the female body perhaps allows the flâneuse to move beyond the general failure of Situationist strategies such as dérive.9 Unlike her male counterpart, who wanders, the flâneuse and her/their public body do engage in a transgressive gesture: she/they go where they are not meant to, thus challenging the dominant urban topography in ways the flâneur perhaps never could. The flâneuse resists the looming threat of violence that is inherent to the female body’s exposure to the city. Pushing the timely expansion of the flâneuse’s radical gesture further, I’d find it helpful to invoke the imaginary of the witch as suggested in the tradition of Marxist feminist geography. Silvia Federici writes that “[v]iolence against women is a key element in this new global war [against collective solidarity, LC], not only because of the horror it evokes or the messages it sends but because of what women represent in their capacity to keep their communities together and, equally important, to defend non-commercial conceptions of security and wealth.”10 It is a new hunting of the witch that targets not only women but queer cultures and their promiscuous refusal of both being an object of patriarchal structures and of reproductive function, considered as threats to popular power. This contemporary witch-hunt is happening everywhere, in cities and online, in work and domestic contexts; the state and capital begin to exert a new type of control over bodies to control procreation and make sure that procreation is productive. Mahmoudi and Sabatino agree that “Witches present a direct threat to capitalism: their way of being and communal tendencies endanger capitalist futures.”11 In their words, witching the flâneuse becomes a figure of resistance against the digital update of urban misogyny. For this digital update we only need to look to the resurgence of the manosphere and the figures leading its renaissance out from an underworld into the mainstream, such as Jordan Peterson, or Andrew Tate with his latest ambition to become Prime Minister of the United Kingdom via the launch of his political party in 2025: the BRUV (for “Britain Restoring Underlying Values” party.)

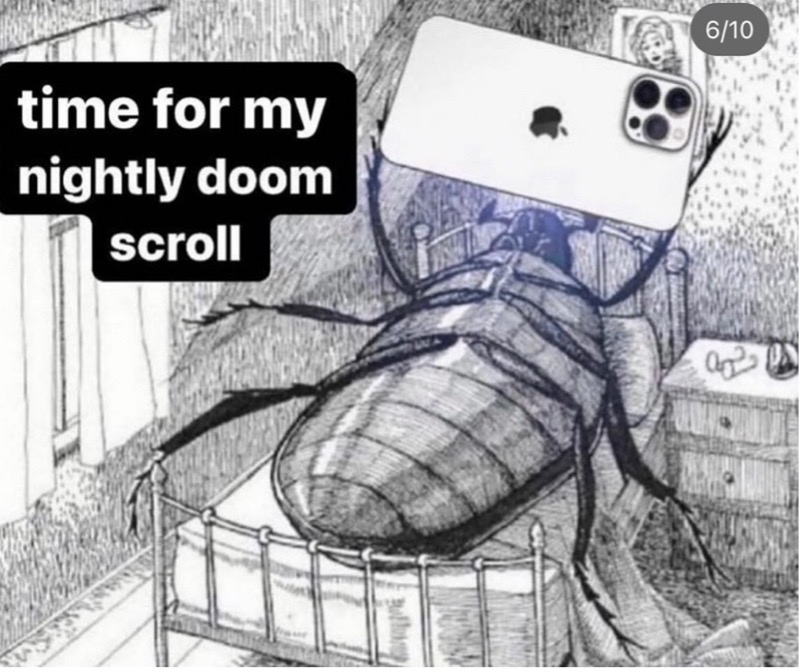

The embarrassment and awkwardness of the (political) spectacle that we are witnessing, namely Trump 2.0, have become more deeply embedded in our everyday lives than Debord could have expected. As T.J. Clark puts it, “the spectacle, as a concept, was accompanied by the idea of the colonisation of everyday life”, in which information, images, advertisements, communication tools, and rituals, are part of the means of its production.12 Our minds are colonised by new signifiers and semiotics, which can manifest in the form of new rituals of communication offering varying degrees of affection and intimacy,13 or as new colloquialisms that settle into everyday speech. Contemporary rituals in virtual communication can include the sending and receiving of stickers on messaging platforms or the sharing of memes or reels on social media architectures as a way of expressing certain emotions in lieu of using words, or as a gesture of connection (“I saw this and it made me think of you.”) Examples of the infiltration of everyday speech with such new colloquialisms are how company, brand, and product names have intercalated our lexicon via a process technically called anthimeria in rhetoric, meaning when one part of speech is used as another, such as a noun being used as or “verbified” into a verb – like how “googling” has become shorthand for searching online, or “to uber” meaning to make use of any one of the many ride-sharing apps to get from A to B.

Instagram account @iwanttoleaveok posting a photo of an Uber Eats worker in Metepec, Mexico

Feminist research approaches into micro politics, such as minor theory or autoethnography that have recently become popular in critical media and internet studies, can contribute to new psychogeographical approaches and practices. For instance, in my own research I blend personal experience with critical analysis. I record my emotions before and after scrolling on Instagram on a daily basis and keep track of how many times I order from food delivery platforms. I noticed that when my mental well-being is low, my daily screen use is higher, and my bank account reduced due to compulsive ordering online. Though I try to be witchy, resist, and conspire against pervasive feelings of co-dependency with technologies – sometimes I fail.

Found via @urlocalmilfuckerr on Instagram

In the seventies, Henry Lefebvre taught us that urban space is neither an idea nor just an empirical given but something that is produced.14 Later, David Harvey took up this idea when proposing the “right to the city” as the condition under which the boredom of everydayness can be interrupted by the collective envisioning of “something different.”15 Applying this to the question of psychogeographies of the present, our feminist demand towards the digital should be for it to become an imaginarium for such heterotopias. As feminists, we cannot give up on the idea of reclaiming technology for the sake of collective urbanism and the greatest forms of pleasure in the city. Even if it is demanding the impossible, digital infrastructures need to serve out exploration of liminal social spaces where “something different” is feasible. As Harvey remarks, this “something different” does not necessarily arise through conscious planning; it emerges out of what Sebastian Olma defined as “the serendipitous convergence of what people do, feel, sense, and come to articulate as they seek meaning in their daily lives.”

To start thinking in this direction, I propose the notion of psycho-digital geography. It takes its cue from McKenzie Wark’s 1994 examination of how emerging virtual spaces—shaped by media, communication networks, and technology—transform our understanding of physical geography, social relations, and embodied experiences.16 Wark had the premonition of conceiving of the places in which we operate, work, sleep, and socialise in the 21st century as “virtual geographies.” If Debord defined psychogeography as “the study of laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not,”17 today these laws are at least in part written by the algorithms that impose a vacuous perfectionism on urban aesthetics (including the bodies within it) that has little to do with reality. It is too easy to blame individual activists, artists, or influencers, for manipulating their bodies into the reductive imagery of self-marketing, when what we should recognise is the extractive and exploitative relation to oneself that the digital platforms create and perpetuate.18

In a feminist psycho-digital geography, the digital must evoke a space of possibilities and intervention, reclaiming the technology that under the auspices of Musk, Zuckerberg, and Bezos has degenerated into an infrastructure of individualistic machine learning and the premium mediocre. This rampant trio of badly ageing boy kings19 are pushing the future deeper into a realm of nefarious banality where the difference between human lives and marketable objects evaporates. Achille Mbembe called this state of affairs “necropolitics,” defining it as “the tension between the free circulation of property and the political freedom of subjects.”20 The society of the necropolitical spectacle is constantly projected onto our screens, no subscription required. Feminist psycho-digital geography can open up self-study and auto-ethnographic adrift experiences in the city that can reveal potential points of intervention in insurgent digital practices. In my own practices of constant self- and critical analyses, I observe that my personal traumas and experiences are unable to be replicated by any digital tools, that navigation systems are fallacious in providing directions, and that chatbots have never solved any of my problems. The problem is not the technology per se but the regimes and power order behind it. We do not need a new app; we need a revolution.

We can collectively contribute to witchy-inclusive machine learning. We can whisper to our algorithms and tell them which content to watch. We need to cheer for defiant collective bodies and imperfections in spaces and places. We have to try something small, different, insurgent, and politically significant… Otherwise, we will remain at once the forced spectators as well as the products of this Spectacle of Cringe!

Source: @thefemmemoon on Instagram