A banal psychogeography of the present rates the world on a scale from one to five. Digital maps have added new layers of information to the representations of old: In addition to locating a place with contact information, it is now the norm for digital maps to offer crowd-sourced ratings and comments for each entry. If we consider all of history through the lens of who stole whose maps, today, we could say that every online map contains a collective psychogeography of a place – told through ratings.

Rating functions have become prevalent in most digital systems. They overlay our cities, our stores, and our daily experiences with a flood of recommendations and warnings. We are told this reviewing behaviour promotes high quality services. Going beyond that, online ratings and review comments shape our perception and experience of offline spaces and services. They influence our choice of restaurants, doctors, and products. On the Internet, any customer can become a reviewer, any tourist can become a guide. Dining out gives anybody the power to play restaurant critic.

Google Maps’ online platform can be used to “add” places, and to review places added by others. Every beach, public square or hairdresser can be rated and reviewed on this platform, using the standard scale of 1-to-5 stars (5 stars being the highest of praise, 1 the lowest). While positive reviews may help raise the value of properties and businesses, they also raise expectations. This space of expectations fosters a special kind of negativity that characterizes review systems.

Reviews supposedly build trust, so private business owners often encourage their customers to write positive reviews. However, commercial marketing reports estimate that only 10% of customers post reviews online, while 93% of customers read reviews before choosing a product or service.1 Most of them specifically look for negative reviews and decide whether to buy products based on them.2 Negativity brings a real, relatable sense of experience, which may reassure customers about a bottom line: the product may be bad in specific ways that they are able to cope with.

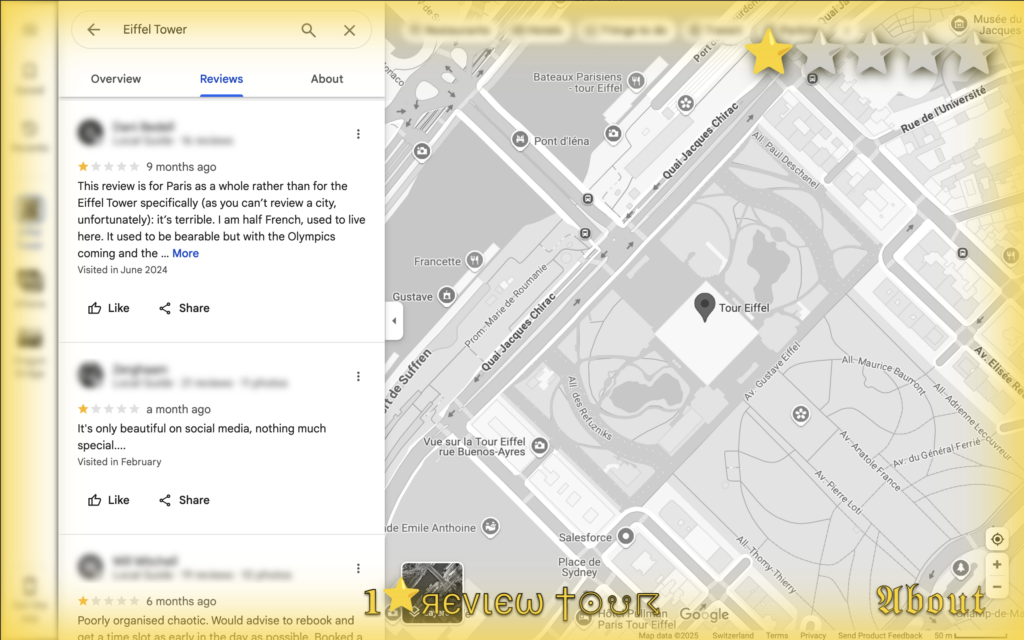

1 ⭐ Review Tour Browser Extension (screenshot), browser extension for Chrome and Firefox. Reviews for the Eiffel tower, Paris, France

Negative ratings also hold value in their own right: A certain amount of negativity improves credibility – a perfect 5.0 rating may be viewed as a fake, while a 4.8 rating with many reviews speaks for high quality.3 So, while the lower end of the rating scale affords space to voice critique, it also gives authenticity and credibility to both the platform as a whole and the rated place individually. In addition, writing negative reviews may also have a soothing effect to counter the frustration and powerlessness we face when the experience does not go our way. For the readers of the negative reviews, reading angry and harsh critiques of the products or places we love can be disheartening and requires special coping strategies.

The 1-to-5 evaluation scale matches the number of fingers on a human hand. Perhaps because of this, it feels familiar and is a simple enough scale for customers to sufficiently assess a range of quality levels across a variety of domains. There is metaphorical significance in 5 ⭐s symbolising complete satisfaction like extending all the fingers of one hand into a “⭐” shape. The evaluation scale is intuitive, relatable, and accessible. This reinforces the idea that rating is objective and meaningful, that a universal agreement on what constitutes “a two” or “a four” can be achieved.

Art Historian Emanuelle Lugli studied the development and politics of measurement from European medieval practices to today.4 He showed how measurement was conflated with objectivity and universality by different power dynamics and belief systems. He also examined the moral and philosophical implications of measurement, questioning its claims of timeless accuracy. Every push toward uniformity in measurement obscured local practices and perpetuated illusions of precision. This is how measurement shaped historical conceptions of truth, reproducibility, and trust.

Coming up with ratings and reviews for a place or site of attraction didn’t originate in digital maps. They were invented towards the end of the 19th century with the start of the “tourist era” when a growing number of people acquired the means and the spare time to travel. Historically, rating was done by trusted experts. The English author Mariana Starke published the first known book to use repeated symbols for ratings. In the 1820 guidebook Travels on the Continent: Written for the Use and Particular Information of Travellers, based on her visits to France and Italy after the end of Napoleonic wars, Starke used exclamation marks to indicate works of art of special value.5 One exclamation mark identified interesting places to visit, three or four signified that the place was a must-see. John Murray’s Handbooks for Travellers (published from the 1830s to the 1910s)6 and the Baedeker Guides (first published in 1854) both borrowed this system, using ⭐s instead of exclamation marks.

1 ⭐ Review Tour Secrets, video, 4K UHD, 60fps, sound, 20'15", loop.

Today, the 5 ⭐ scale is one of the most common classification systems in use. Ratings are increasingly offered to customers on reseller websites or general-purpose centralised platforms, evaluating everything from films and TV shows to restaurants, hotels, and public spaces. Such practices of crowdsourcing ratings and reviews is enabled by online platforms aggregating data on products, customers, and businesses, and acting as data brokers. Google Maps, Tripadvisor, shopping sites like Amazon, eBay and Alibaba allow users to describe their experiences and rate places and products. A collaborative narration of the contemporary, an endless stream of recommendations, expectations, frustrations, of thrills and disappointments.

Written collectively by thousands of people, reviews serve as testimonies of past frustrations and as coping mechanisms of shared emotional expressions. They are snapshots of the psychogeographical present. They trigger therapeutic release. In this world voicing negativities in the review section is the “massage” – a way to soothe frustrations and deal with feelings of powerlessness. But how did we arrive at this moment where collective discontent intertwines with our physical landscapes?

Reviews are part of a specific business logic that puts the businesses providing products, services, or places, and their customers into a relationship of (mis)trust. They operate within the so-called social quantification sector that appropriates human life into data relations.7 Online rating systems are driven by what Ulises Mejias and Nick Couldry called monopsony.8 Platforms circulate reviews generated by the users and their interactions without compensation. Coincidentally, they are the only market for the data we produce.

On the Internet, social relationships and market relationships have become blurred. Riffing off the well-known Facebook moto “connecting people,” Ben Tarnoff identified the Internet as an instrument which brings people together under the sign of capital.9 He also warned about the misleading effect of the “platform” metaphor these websites use. The term projects an aura of openness and neutrality, which is in stark contrast to the private and opaque governance that companies like Google or Meta impose within these spaces. They control the spaces of our digital lives, while obscuring their governing principles and producing the semblance of user participation.

Because the privatisation of formerly public spaces and infrastructures of the internet has a history, Tarnoff argues, it can also come to an end.10 Private internet is in no way “natural,” it is a chain of decisions, conducted through public policy. De-privatisation has to be inventive: it needs to be built on community networks, be less competitive and rely on protocolising social media.

Like the privatisation of the internet, the connection between advertising and trade has a history that is older than online platforms. One of the oldest known customer complaints was written on a clay tablet to the merchant Ea Nasir from the ancient city state Ur. This is a complaint about the wrong quality of copper having been delivered. The tablet, unearthed by a British archaeologist in southern Iraq today is the property of the British Museum in London. The Museum itself, along with many other imperial collections have been strategically targeted with negative reviews on Google for their ignorance of restitution requests for looted objects.

Because platforms are organised around the notion of property and ownership, a place with an owner or representative like a restaurant or a museum can respond to negative comments and request to take down harmful reviews. But this opportunity to correct false or inappropriate reviews is not afforded to public spaces, to public goods and to public services. A beach or a children’s playground cannot defend itself – it is left to exorbitant demands and expectations from everyone, while no one in particular is responsible for the reviews. And just as platforms and Big Tech increasingly replace public institutions with privately controlled for-profit services – the “rating regime” strengthens private business – they are simultaneously undermining public spaces. Just check out the online reviews on your nearest park, your local tax-office or a school in your hometown and you’ll see what we mean.

Beyond rating a place from 1 to 5, review platforms have unintentionally also created fertile grounds for subversive intervention. When real-world values and services hinge on this “rating regime,” the system and its automated algorithms can be, paradoxically, be weaponized against itself. Strategies such as review bombing, counter-marketing, or institution-shaming disrupt the extractive logic of the platform, turning its own mechanisms into tools of critique or resistance.

Review bombing is a strategy where a large number of people post reviews in a coordinated attempt to influence the public opinion of a place, service, or product. High-profile restaurants faced extortion from scammers requesting payment in Google Play gift cards in exchange for removing negative reviews.11 Reviews can also be used to boost businesses, real or fake, to achieve top ratings by gaming the algorithms of the rating systems. Another example of platformed critique is how the Google Map entries for European ethnographical collections and museums are being used to protest the lack of acknowledgment of colonial heritage in their collections.

Review-bombing also gets used in fan culture. In Chinese internet culture and its slang, positive review-bombing by fans is called cǎi hóng pì in Mandarin, which translates into English as “rainbow fart.” Rainbow farts are over-the-top compliments that fans shower their pop idols with online. The term implies that even the idol’s flatulence looks and smells like rainbows. For fans, their choice of idol feels as a showcase of their own personality and is a way to relate to others. So, the idols must be defended at all costs.

Interventions like this show how collective agency can appropriate a digital system to carve out a space and voice approval – or dissent and opposition. As artists we use similar strategies to question the smooth and surreptitious arrival of the now-default way of navigating the world through the lens of online ratings. We focus on negative Google Maps reviews to shift perspectives on rating systems towards collective concern for shared infrastructures and provide insight into the failed expectations of travellers within the global tourism-industrial complex.

At Aksioma Project Space in Ljubljana, we created a “massage” studio for the viewing of 1 ⭐ reviews. Visitors could read and listen to negative comments about their city while relaxing their bodies reclined in an electric massaging chair. A video essay about negative reviews was shown to people through the face cradle pad of the portable massage chair. A yoga mat welcomed the audience to lay down and navigate 1 ⭐ reviews of Ljubljana through a browser add-on, while resting upon a face down gaming cushion. The coupling of intensified negativity with comfort and touch massaged their sense of attachment and responsibility to places that are negatively rated by these systems.

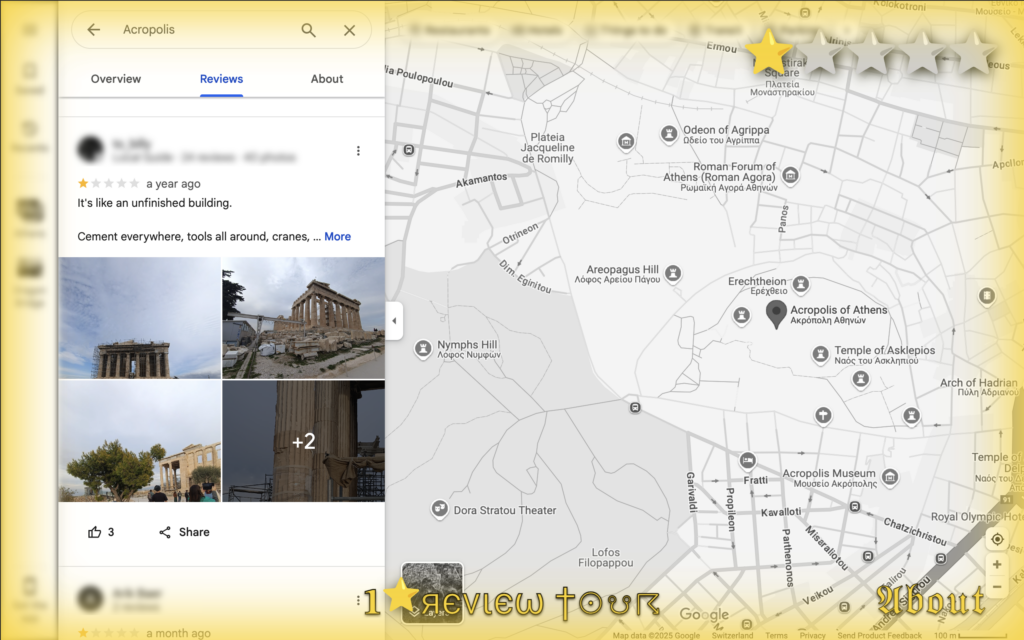

With the browser add-on “1 ⭐ Review Tour browser extension,” we challenge the deeply ingrained and seemingly objective filter of Google Maps and entirely shift your perception of it.

Try it here → https://★☆☆☆☆.yugo.at

1 ⭐ Review Tour – The Browser Extension instruction video

By filtering out everything but 1 ⭐ reviews, this extension gives you a “nightmare” vision of the world. Yet, the nightmare is not just in the reviews themselves, but also in the underlying system they represent. The 1 ⭐ lens highlights the absurdity of reducing reality to numbers, of quantifying lived experience into ratings and ⭐s, and analysing these fragments with statistical tools to make everything more ‘efficient’—and ultimately, more profitable. The extension does not simply show you negative reviews; it lays bare a critique of the very structure of platforms like Google Maps that commodify and optimise human experience under the guise of utility.

We are not the only ones deploying such strategies of platform critique through the 1 ⭐ lens. Making selections of negative reviews to counter the predominant narration of “good” and “important” has almost become its own genre: a Youtuber recounting 1 ⭐ ratings of products; a beautifully designed book on national parks with negative reviews as art;12 a book on non-notable artists whose biographical articles have been removed from Wikipedia.13 The list goes on. Collecting negativity in order to tell a different story is a way to make visible, and thereby provide the potential to resist, the dominance of the tech industry and its extractive approach to crowd-sourced content.

Digital data, such as ratings or reviews, have real world consequences. Not only do they directly influence the opinions of users, but their aggregated data is also fed into recommender systems. It filters our access to the world, generating a psychogeography mediated through the digital.

1 ⭐ Review Tour Browser Extension (screenshot), browser extension for Chrome and Firefox. Reviews for Acropolis, Athens, Greece

To bring reviews into a matter of public concern through art or activism is one possible step to question the role and societal value of current reviewing practices on online platforms. A critical approach to rating systems opens them up for, and provides access to, public debate. By engaging critically with recommender systems, we challenge the belief that they are useful or necessary. We highlight ways for thinking about and making digital systems that engage with our built environments in a way that promotes the public instead of the private, and collective interests instead of only those of businesses. Understanding that the digital rating systems have become the norm through which we look at the world, helps to emphasise the importance of de-normalising them. Reiterating on Guy Debord’s observation that our environments effect our emotions and behaviours, the reflections on 1 ⭐ reviews presented here, explore the effects of virtual platform environments. These platforms privatise collective experiences through algorithmic regimes of rating and recommendations. By reclaiming digital spaces as spaces of solidarity and as de-privatised public spaces outside of business logics we are also reclaiming our contemporary psychogeographies.