In the bestselling young-adult fiction trilogy The Hunger Games (2008-10) and the subsequent blockbuster film franchise (2012-present), children are forced to murder one another in the titular televised gladiatorial spectacle, all for the pleasure and glory of The Capitol, an exploitative dystopian regime. As the series proceeds, our heroes refuse to be human sacrifices in the sadistic games and, instead, lead a revolutionary insurgency. But they soon discover that, institutionally and geographically, the Capitol is a mind-bending labyrinth of games within games, and the series ends ambivalently.

In one of the most successful TV serials of all time, Game of Thrones (original series 2011-2019), warring elite families of a fantasy kingdom toy with the fate of several continents through eight blood-drenched seasons. Deftly combining palace intrigue with highbrow pornography and gratuitous violence, the series captivated its viewers for nearly a decade with the recursion of political games within games, from which no clear winner can emerge. The show’s core creative team would, in 2024, release Three Body Problem, a series based on the bestselling Chinese science fiction trilogy that begins with a novel of the same name (2006-10 in Chinese, 2014-16 in English). The plot includes malevolent aliens covertly recruiting humanity’s top scientists to their cause through a beguiling but unwinnable video game.

Game of Thrones would then be displaced from its own throne in 2021, when the South Korean Netflix drama Squid Game became the most streamed series ever, depicting a world where hundreds of heavily indebted people are manipulated into travelling to a secret island to compete in a sadistic and lethal versions of children’s games for the pleasure of bored and perverted billionaires, the last survivor entitled to a huge cash windfall. As the first series ended with our good-hearted hero the reluctant and traumatized victor of the vicious tournament, we are led to believe that an even greater game is afoot. The sequel series (2024) was more of the same.

One of the top-grossing, most downloaded and most played video games of all time, Fortnite (released 2017) places players’ warrior avatars in a never-ending battle royale, wars of all against all, where the last one standing takes the title and where there is no greater objective than to gain and maintain prestige, power and ranking. This idiom is echoed in any one of dozens of blockbuster “reality TV” franchises, most recently The Traitors, where contestants must slowly betray and eliminate one another until (usually) only one remains.

What are we to make of the startling global success of these spectacles? Certainly, the theme of being trapped in a violent, unwinnable game has precedents, but it has never been so popular. Perhaps it is because the vast majority of people living under the direct rule of capital in the 21st century also feel like they, too, are caught up in an unwinnable but compulsory game?

Already in her 2007 book Gamer Theory, McKenzie Wark speculated on the sublation of what Guy Debord dubbed the “society of the spectacle” into what Wark calls the gamespace. Here, where the idiom of the game pervades society and all social subjects, not just gamers, are haunted by the uncanny sense that they are trapped in some sort of game. Today, this structure of feeling finds its hysterical expression in the millions of people who participate in gamified online conspiracy communities to share evidence that the world is, in fact, a vast simulation. But even where suspicions are never voiced, the disquiet remains: today, we almost all feel, to a significant extent (if in different ways), trapped in an unfair, inscrutable and unwinnable game. What political affects, structures of feelings and psychogeographies take hold in such a situation?

On one level, this may be the result of at least twenty years of “gamification,” a term that generally describes the application of game mechanisms, processes and enticements into non-game atmospheres. While play is perhaps elemental to all human (and many animal) forms of learning and sociality, and while many civilizations have used games for millennia to train people for care, for war, and for much else besides, gamification names something newer, unique to the dangerous convergence of the finance and tech sectors so characteristic of capitalist power in the 21st century.

Here, games and play are broken down into their most elemental components (the dopamine-inducing hit of constrained agency, the urge to safe competition, the proxy for collectivity offered by episodic cooperation) and then synthesised into other digitalised vectors of late capitalist life. Banking apps use game elements to reward us for good behaviour; dieting and health apps use leaderboards to nudge us towards hygienic behaviour; education and learning apps create a user-friendly panopticon; dating apps turn us all into avatars.

Critics of the trend often satisfy themselves with warning us about the grim uses of the data we players generate, that is now commodified and speculated upon. This data may soon be used (or is already being used) to target us for customised spam (if we’re relatively high up in the hierarchy of human disposability) or a drone or airstrike (if we’re not). Other critics note the way gamified interfaces, which have been birthed by an unholy alliance of software engineers, neuroscientists and venture capitalists, wreak havoc with our bodyminds, captivating and habituating us with apps calibrated to excite, reward and render dependent our ill-prepared mammalian neurotransmitters. To these we may add that the norms and values embedded in and encouraged by these gamified platforms (bourgeois financial responsibility, extrinsic enrichment of human capital, transactional romance) function as a kind of meta-ideological apparatus, hailing us silently, from within.

We might be said to live in a kind of decentralised totalitarian regime, where all aspects of life are dictated by the market. As compelling a fable as it may be, the dystopian world of The Hunger Games, where totalitarianism takes the form of a centralised state using naked violent repression, is ideological misdirection. In contrast to a regime that utterly represses all human agency, the regime of gamified capitalism relies on using gamified mechanisms to entice, seduce and channel our agency, holding our social reproduction at ransom.

The development of gamified platforms is not some random or necessary development of human technology. Rather, driven forward by the entanglement of speculative finance and the tech sector. The former is eager to plough its ill-gotten wealth into the latter, which must in turn constantly prove an expansion of userbases, an ever-more successful harvesting of attention, more engagement and greater user dependency. Needless to say, the financial returns almost exclusively flow upwards. Meanwhile, at a systemic level, the spectrum of gamified interfaces with which we engage every day, in sum if not always individually, have the effect of installing in each of us a post-disciplinary system that, ultimately, makes our labour power cheaper, more accessible and more pliable for extraction.

For this reason, to focus exclusively on the very real dangers of gamification in a limited frame would be to risk missing a larger, even more important picture. The 21st century financialised capitalist economy in which we all participate is, indeed, a kind of vast game, unwinnable for the vast majority of us. Within it, almost everybody is exhorted to adopt this disposition of the player, the savvy risk-taking agent, operating both within but also bending or breaking the rules in a competition of all against all.

In his bestselling 2024 autobiography The Trading Game, Gary Stevenson offers detailed account of his rise from London working class origins to becoming one of the world’s most successful financiers around the time of the 2008 financial crisis. He reveals how investment banks and hedge funds identify and recruit new talent through poker-like betting games, and train and retain them through gamified protocols and platforms that make the movement of billions of dollars of wealth a form of play. Veteran financial reporter Michael Lewis has often revealed the importance of games among financial insiders, notably in his breakout tell-all Liar’s Poker (1989) and more recently in his insiders’ view of the empire of convicted crypto-Ponzi schemer Sam Bankman-Fried, Going Infinite (2023). The latter book makes clear how important video, tabletop, and live action role-playing games were to the corporate culture of the firm that was, until its frauds were revealed, heralded as the future of finance. Numerous scholars have made clear that the line between gambling and allegedly economically productive financial speculation has never been clear. But if it is somehow a game, the consequences are deadly real: it directs the accelerating flows of global wealth that entrench wealth and poverty and fuels the extractive industries that are murdering the earth. Individual acts of strategic or tactical play, in sum, produce an almost universally catastrophic game, hidden in plain sight.

Perhaps in every regime, games are a mechanism to seduce young men into acts that perpetuate systems of unspeakable cruelty. The drone pilots that have been weaned to kill on violent, dehumanising video games are the postmodern echo of the war-gaming elite officers of the Napoleonic Wars, those sons of privilege, who commanded working class soldiers via perfumed letters, following the action on exquisite tabletop models, the pieces moved by servants. Today’s financial engineers who program supercomputers to do algorithmic gladiatorial battles against one another for the profit of their masters are the echo of the heavily armoured knights of old, who waged sporting wars that killed and maimed mostly unarmoured peasants. It’s not coincidental that today’s financial robots are built on the basis of so-called “game theory,” a school of thought developed primarily by American engineers to calculate how a nuclear war might be won and which soon became an important part of the neoliberal worldview and policy apparatus, with its presumption that all actors are either competitive and acquisitive… or simply stupid or incompetent, destined to drag the winners down.

As financialised neoliberalism came to supplant Keynesian political economy in the last half-century, the idiom of the player seeped into the social fabric. As principles of social welfare gave way to individualised risk-management and competition, those with the means to do so were encouraged to play the market. It was not only that, thanks to the affordances of ubiquitous networked computing, it became easier than ever for those with means to try their hand at investing, including on gamified phone apps that trigger in us psychochemical rewards indexed to the performance of our miniature portfolios. Though it presented itself as a popular insurgency of Davids against the Goliaths of Wall Street, the crypto craze was little more than a systemic side hustle, a grimy, scammy craps game out the back for those not dressed well enough to get in the casino. But the game was, essentially, the same.

Even beyond direct forms of investing, we have all been exhorted (and occasionally rewarded) to remake ourselves as players of a financialised game that now pervades almost all aspects of life. Houses became vehicles for investment; education became an investment in one’s human capital; exercise and diet became investments in health and wellbeing; personal connections and relationships became investments in social capital. Lest we believe this paradigm only extended to the borders of middle-class delusion, it ought to be noted that domestic and international “development” agendas have, over the last three decades, increasingly taken their cues from the paradigm of the player. The subprime mortgages that triggered the 2008 financial meltdown were intended to give poor Americans access to the financial game of home ownership and leveraging. The (largely abandoned) craze for microfinance lending, or today’s enthusiasm for “fintech” (financial technology) rests on the idea that new technologies and market mechanisms will unleash the competitive spirit of the world’s poorest people, making them players too. While in many ways this game-like competitive imperative is coded as masculine, we should not ignore the many ways that liberal/white/girlboss feminisms advertises itself with the promise that women can and should prepare themselves to play and win at the boys’ game, nor the reality that by far the most popular aspiration of girls and young women around the world is to leverage a dependency on social media platforms like Instagram or TikTok to become an influencer, nor the way that patriarchal romantic and relationship norms are (once again) repackaged as a game that can be won through tactical moves and a strategic mindset.

Meanwhile, everywhere, neoliberal cuts and austerity has been justified by recourse to the idea that those seeking economic support are probably cheaters, scammers and frauds who must be relentlessly suspected, surveilled, disciplined and punished.

This is a world where everyone is instructed to take up the mantle of the player, and yet where everyone is also paranoid that they are being played. And we’re right: the game is indeed gamed. The rich get richer. Things fall apart. We are taught to blame the wrong people.

Capitalism has always been thus. Even Marx himself, who sought to show that the system is, in an ideal sense, ruled by certain laws that go beyond the agency or venality of any particular individual bad actor, readily admitted (and castigated) the competitive gaming of the system by various capitalist actors who used monopolies, cartels, bribery and all manner of financial chicanery to rig the capitalist game. Today, only the most delusional neoliberal economist could convince themselves that the capitalist game isn’t utterly corrupted. The manipulation of domestic and international law to create tax havens (no relation to the author) is only the tip of the iceberg. Scandal follows scandal follows scandal, and no one is surprised.

But something is also different now. In previous moments of capitalism, the class system appeared far less fluid. Capital was largely invested in exploiting workers’ bodies. While it may have provided a few opportunities for the entrepreneurial spirit of middle and working-class people (often in the form of a share in colonialism or the domination of a frontier), conformity and stability were both the norm and the (false) promise.

Today, massive profit (and perhaps even surplus value) is generated through consumer debt and credit. Whatever stability capitalism once promised to the middle class is gone, replaced with the imperative to innovate, compete and manage one’s own risks, to play the field. Moreover, capitalism as a set of social relations expands, in part, by making each of us its pioneer, tasked with “colonising” new spheres of life, now as entrepreneurs, now as influencers, now as gig workers turning our bedrooms into hotels, our cars into taxis, our hobbies into side hustles, our charisma or wit into “content,” all held to ransom by proprietary platforms that play us for fools.

In other words, structural changes in neoliberal, financialised capitalism over the past 50 years have meant that we have all had to, in various ways and to varying extents, adopt the habitus of the player. And yet the fable that this system had delivered us a level playing field is constantly belied. The game is rigged. We find ourselves in a world of cheated players.

Unfortunately, this reality only rarely manifests a systemic critique. More often it generates conspiracy theories, the urge to punch down or absurd fantasies of escape. As the late Fredric Jameson argued over three decades ago, today’s conspiracy theories can be seen as faulty but beguiling “cognitive maps” that attempt to offer a resource for generating a holistic and cohesive view of a world chaotically fragmented and fissured by the pressures of financialisation. They attempt to explain why the game is rigged: they hallucinate a kind of meta-human agency, a superplayer (an evil mastermind, a cabal, a secret society, an alien intelligence) that is stacking the deck or loading the dice.

Increasingly, and very dangerously, this kind of conspiracism dovetails with the idea that unscrupulous “minorities” are gaming the system, playing the long-suffering majority for rubes and chumps. The European template of such conspiracism is, of course, the modern antisemitic conspiracy complex. But today this model is applied to trans people accused of toying with gender and children for their own dark pleasures, to Muslims held to be playing a secret game to “replace” white Christian populations, to refugees and other irregular migrants who are rumoured to be exploiting the goodwill and sportsmanship of a nation of earnest entrepreneurs.

Meanwhile, even dreams of liberation are caught up in the game. It would be misguided to imagine that the last decade of cryptomania was simply delusional. It represented (and became) for many young people a means of participating in the financialised game foreclosed to them. For those Keir Milburn hoped would emerge as “generation left,” who had no access to invested capital (like savings or houses) and who also felt acutely the hopelessly diminishing returns of investments in their “human capital” (infertile university degrees), crypto investment as well as memestock play, like the infamous Gamestop gamble, were imagined as methods to exit the rigged game of their parents’ capitalist economy and jumpstart a new one, where the real players could, finally, get what they deserved.

I have elsewhere theorised this tendency through the lens of revenge. Gamified, financialisation capitalism’s annihilation of any other potential futures and its relentless reduction of all of us into cheated players lends itself to a turn towards a revenge politics that is a grim reflection of the vengeful economy from which it emerges.

The nihilism, cynicism and spamminess of today’s far right and neofascist leaders, and the key to their success, lies in the way they appeal to a world of cheated players who feel trapped in an unwinnable game. Their apocalyptic rhetoric and viciously vindictive policies, which occasionally promise to punch up but always only punch down, appeals to subjects wrought of four decades of financialisation. That so many of today’s clownish fascist personalities are conspicuous cheats is fitting: like the stage magician who trumps his rivals by showing the audience how the trick is performed, the cheater-in-chief empowers his followers by promising to reveal how the game is fixed, and to take revenge on their behalf.

In the 20th century, fascism first and most successfully festered not in the dispossessed working classes, but in the downwardly mobile petit-bourgeoisie, who felt they’d played by the rules and been cheated of the pride, security and normative life they’d been promised. So too today, in 21st century fascism, except for two things.

First, financialisation has seen the proletarianisation of the petit-bourgeoisie as more and more forms of “professional” work in the so-called “knowledge economy” have become precarious and subject to profound market discipline. This, as well as an increasingly international labour market and competition mean that those that considered themselves “middle class” feel, everywhere, under threat and cheated.

Second, financialisation and neoliberalism have been so successful in their decimation of working class identity, consciousness and communities that, today, we are witnessing the horrific ideological consequences of the petit-bourgeoisification of the proletariat. Today, everyone has learned to identify with the morality, expectations, dispositions and ambitions of the phantom middle class. Everyone is a player, tasked with leveraging their assets even if they don’t have any, investing in themselves even if there’s no real hope of payback.

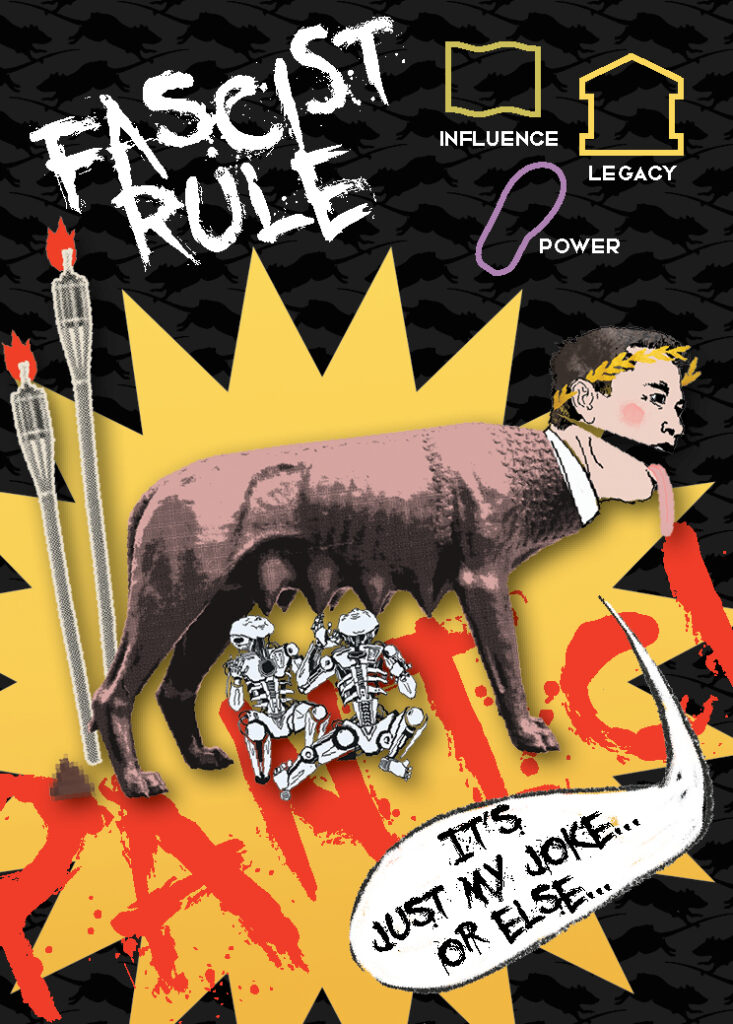

Neoliberal financialised capitalism has bred within it a form of fascism that both mimics and exceeds it. This is a fascism where the cheated would-be players, rather than ending the rigged game, take sadistic revenge on those they blame for cheating.

It would be tempting to imagine that games are inherently anti-fascist because they reject fascism’s rigid ordering of human passions. But this would be to fatally misunderstand how 21st century fascism differs from its 20th century ancestor. They each emerge from very different forms of capitalism, the first an industrial and imperialist system that turned the working class into cogs in a machine; now a more decentralised, subtle and seductive system that exhorts each of us to hone our subjectivity and agency to chart our own (doomed) strategy of participation. In 20th century capitalism, it was clear we were all sacrificial pawns, and this was preyed upon by something that the Frankfurt school theorists (prudishly) identified as fascism’s sadomasochism; 21st century capitalism tells us we’re all potential queens, if only we can beat one another in the race to the back row of the chessboard. We must dwell with a new matrix of systemic contradictions, subjective reactions and political affects.

But moreover, today’s fascism is playful. It delights in making serious business a stupid game, and making stupid games serious business. They will hunt you in online packs for making fun of their avatars; they will livestream their massacres on gaming platforms and worship the one with the highest score. Today’s playful fascism flexes by making kings bow to clowns, by changing the rules in the middle of the game, by cheating in plain sight, by mimicking a dozen contradictory ideological positions (libertarian? Royalist? Nazi? Neo-Futurist? Hayekian? Randian?) and insisting, with force, they are all coherent and consistent. And through these actions it espouses, silently but unmistakably, it’s one and only rule: power is, and nothing else. There are only two kinds of people: those real players who make and break the rules, and those NPCs (non-player characters) who obey them and are therefore disposable. It’s all a game, and the game is deadly real.