MAKING & BREAKING (M&B)

Let me start by sharing with our readers that as we’re conducting this interview, you’re sitting in your apartment in Los Angeles while parts of the city are engulfed in devastating fires. Knowing that you are safe there, could I kindly ask you to introduce your work through the lens of a city currently in flames?

LIAM YOUNG

Yeah, we’re safe here, thankfully. Ash is falling like snow as we speak, so it’s kind of apocalyptic. I’m trained as an architect, though really what I do in my practice is tell stories about the architectural, the urban, and the ecological consequences of new technologies. In the end, these are stories about who we are and who we want to be in the future. That is what I describe as new planetary imaginaries, which to say that I’m trying to create new kinds of imagery and new sorts of stories about what our futures could hold. And I am doing so in a moment where it feels like we have no future.

Still from Planet City (2020). Image courtesy of the artist.

The narrative here is that we’re witnessing the most expensive and the largest scale natural disaster that Los Angeles has ever seen. But to call it natural is entirely fictional. This is very much a man-made disaster. Both the windstorm that is fuelling these fires as well as the way that the landscape and the city are organised are all entirely unnatural and go against natural practices of seasonal burns that used to happen, as well as indigenous practices that would facilitate those burns, including moving around to allow the burns to happen. So, we’re seeing what will be the first of many instances of climate change catastrophe both in California, and around the world. Now more than ever, it seems critical to try and find ways to talk about what we can realistically and pragmatically do against this backdrop.

Our images about our future are entirely outdated and outmoded. They’re based on the failed ideals of boomer environmentalism, rooted in a particular idea of 60s and 70s environmentalism that centred our own actions and a certain scale of individual performance of aspirational futures around actions like recycling, being vegetarian, growing your own vegetables, and so on. These are all things that we should be doing as a matter of course, but they do nothing in the context of the scale of crisis that we find ourselves in now. Perhaps in the 60s and 70s, we had a chance with that scale of action, but we’ve well and truly blown past the magnitude that those efforts operate at. Today, planetary-scale action is what we desperately need.

M&B

Planetary-scale action is exactly what your work is addressing. Planet City (2020) builds on the idea of acumenopolis, i.e., total planetary organisation, a vision that has been around for a while and is not exactly new. You quote William Gibson’s Sprawl trilogy or Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series as inspirational texts. Beyond these imaginative explorations and speculations, your work also highlights the reality of the present version of the global city in which the planet serves as a resource for extraction and exploitation, oceans have become conveyor belts, and so on. In Planet City, we join humans and sometimes drones on their processions through these extremely dense cityscapes and this is what makes me kind of think of your work in terms of psychogeography. Is this something that you thought about when you were making this work?

Planet City, 2020. Film excerpt courtesy of the artist.

LIAM YOUNG

Yeah, I guess so. My work has long been inspired by Situationist practices and what one might call the misreading of cities. What I’ve been trying to do with my Planet City narratives is, as you mentioned, kind of drift back and forth between the planetary scale of cities that we all occupy and the Planet City fiction in a way that makes it sometimes difficult to read which of those cities is fiction and which is real.

The real fiction at the heart of the Planet City Project is the idea that we can keep on doing cities the way that we have always have. I’m narrating this story about a hyper dense metropolis for 10 billion people, which in itself is a ridiculous notion and it’s really just a provocation and a thought experiment to get us to rethink our existing cities and start to imagine them in new ways. Most of us live in an everyday global city that has become so shocking yet simultaneously so familiar that we cease to see it for what it is. So yes, it’s very deliberate to try and use the concept of dérive or the wandering through these two stories to immerse audiences in the experience. This may not seem necessarily related to psychogeography, but I often talk about my practice as a form of data dramatisation that sits in opposition to what we typically think of as data visualisation, especially in the context of climate change. Data dramatisation means more than just identifying patterns, rather it is to imbue them with drama and emotion so that we understand ourselves within those systems and feel the emotional weight of what these patterns might mean. In many ways, I use processes of immersion to do that kind of dramatisation and take audiences on walks and tours through these fictions to try and connect people viscerally to those ideas in ways that are more meaningful and harder to ignore, to connect them in ways that they see themselves as being complicit in those narratives.

M&B

I really like the notion of data dramatisation that you just referred to because I was already wondering about the role of aesthetics in your work. I don’t mean just in terms of your own creative practice, but also in terms of the relation of aesthetics to the economic and socio-political landscapes within your speculative visions. The work you assign to the aesthetic within your vision of possible urban futures, as you say, is quite different from the paradigm of the creative city.

LIAM YOUNG

Obviously all images, all aesthetics through which we talk about the future, act politically. They are loaded with cultural biases and ideology. I always remember the imagery that Google released around their now cancelled Quayside project in Canada. This was meant to be Google’s smart city; the most technologically advanced city humanity has ever constructed. They released a set of images that were essentially watercolour drawings with kids running around in bare feet chasing kites and butterflies and people paddling in kayaks. For the largest technology company on Earth to release a series of watercolour renderings for their Future City was really a political act to disguise the massive surveillance system and huge data acquisition processes that would have been involved in making that city work. They tried to use this bucolic imagery to deliberately shift the narrative away from their objective of technologically infiltrating every aspect of our lives.

Choreographic Camouflage, 2021. Film excerpt courtesy of the artist.

In our work, we deliberately try and avoid that kind of imagery; the cute icons of Smart City graphics and so on, which is all part of the smoke and mirrors used to present these technologies as being completely benign and purely in service of making our lives better and more comfortable.

M&B

When you mentioned the watercolour drawings, I had to think of Jane Jacobs, and the way in which this kind of “small is beautiful” thinking inspires much of urban regeneration and more sustainable city planning. To what extent can we understand works of yours such as The Great Endeavour and Planet City as alternative and perhaps more effective forms of placemaking?

LIAM YOUNG

They’re certainly trying to be more pragmatic images of what we think of as a future place. Again, if we were to quickly do a Google search for green futures or utopias, we’d get these images of green rooftops and the community garden that characterise the disciples of the contemporary iteration of new urbanism. Unfortunately, they’re images that are pure fantasy. These are not scalable images of the future as we hurdle towards a planet hosting 10 billion people.

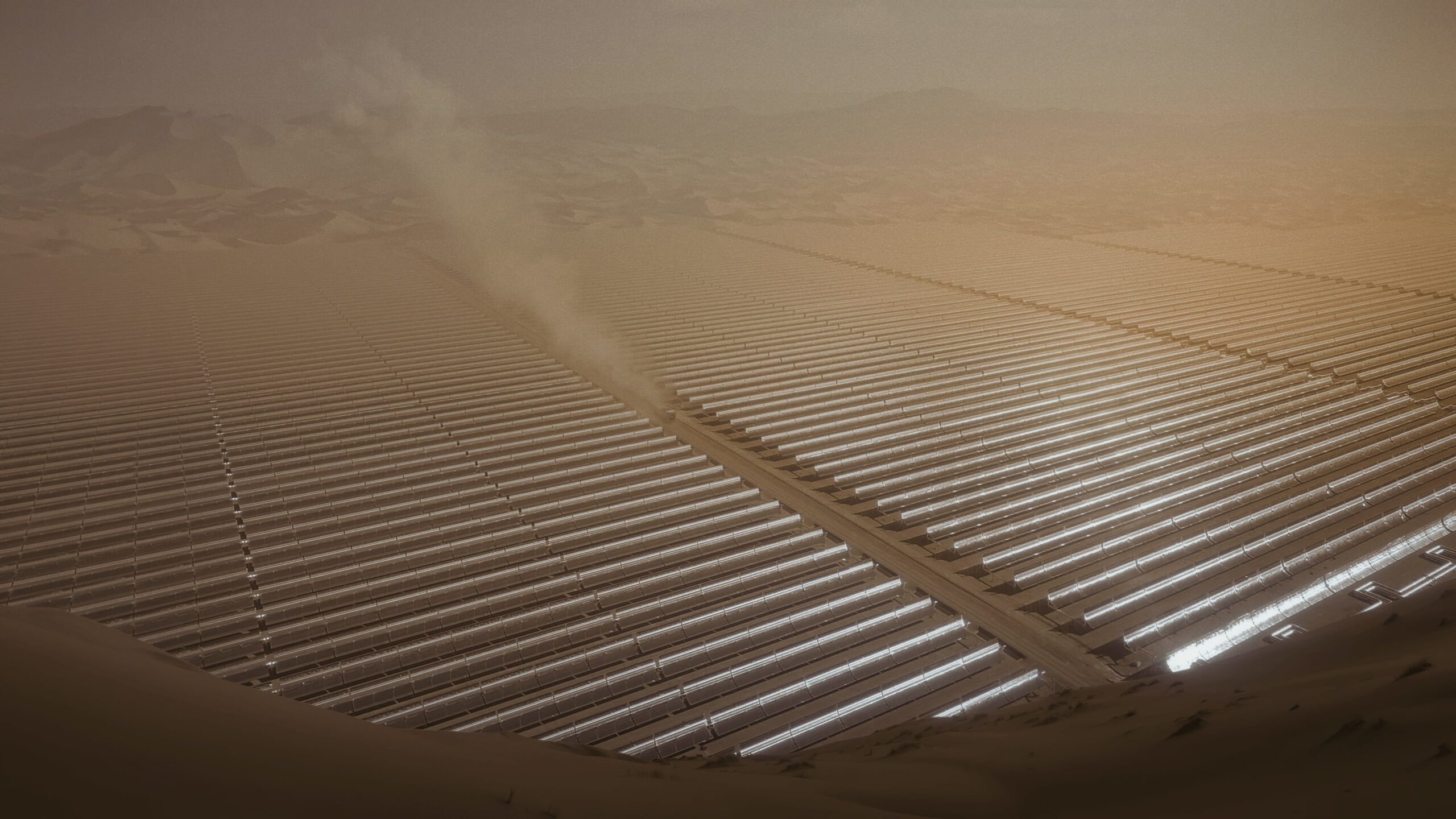

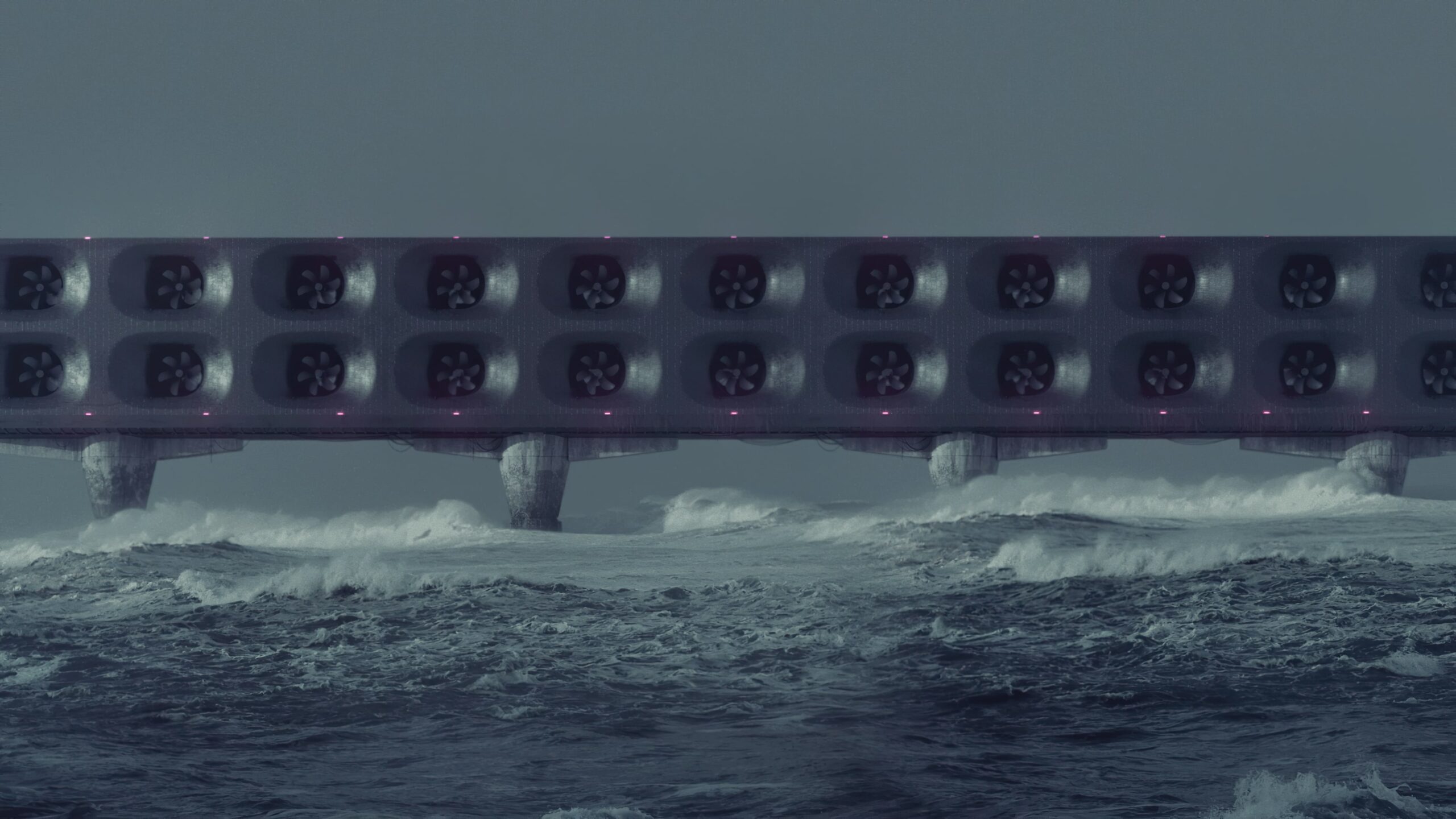

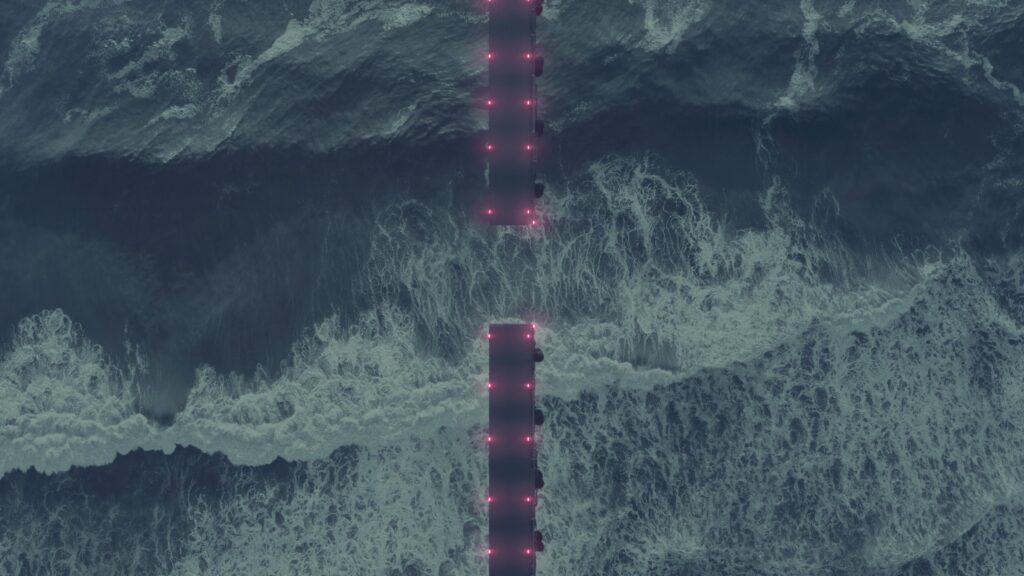

What we’re trying to do with Planet City or The Great Endeavour is to put more viable images of the future into the popular imagination. They’re quite controversial and provocative since they sit in direct opposition to what we’re told culturally. Our future isn’t supposed to be a place where the mega-scale infrastructure of a planetary network of carbon removal exists. Our future isn’t supposed to look like giant walls of spinning turbines. It’s not supposed to look like mirrored deserts capturing the sun.

The Great Endeavour, 2024. Film excerpt courtesy of the artist.

So when people see the images of Planet City, their first thought goes to the cultural construction of density, which is supposed to be dirty and congested – dystopian, really –, even though we all understand that the most vibrant and exciting cities on Earth are the densest.

In our work, we co-opt the visual language and aesthetics of the sublime in our future-making as a means to try and talk about both the wonder of these new systems and technologies, as well as the horror, anxiety, and fear that comes with the fact that we’ve gotten to this point where these are the scales of action that we now need in order to not become extinct. We’re not trying to sugarcoat them and instead, create an imagery of future placemaking that comes to terms with the idea that we are going to be living side by side with this extraordinary infrastructure of massive vertical farms, massive carbon removal infrastructure, massive renewable energy sites.

M&B

Density and scale are largely absent from the current discourse and practice of ecological design. Why do you think this is the case and why is thinking in terms of large scale and density so frowned upon?

LIAM YOUNG

The forms of urbanism and city–making that we were trained into have failed. So many people, extraordinary people, noble and brilliant people, have devoted their lives to trying to enact those kinds of images. As we’ve said, perhaps in the 60s and 70s there was a moment when we had a chance to turn things around by way of such small steps and local actions, but that possibility blew right past us. Admitting that hurts. That’s why we refuse to give up on those images and hang on to the idea that our future is going to be based around the mythology of the local.

Still of offshort carbon removal fans from The Great Endeavour, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.

Pushing against this is really like trying to turn around a giant shipping container. It’s built around an entire infrastructure which is trying to place responsibility on the individual to divert focus from the massive systems that lie behind the scenes of the modern city. Everything is constructed to prevent this from happening. Equally, this rise of nationalism isn’t helping because it means literally turning one’s back on any form of global collaboration or cooperation that something like planetary carbon removal or shifting away from fossil fuels and creating a planetary network of renewables would necessitate.

M&B

The global fragmentation caused by the rise of nationalism and protectionism, and also by the massive proliferation of economic free zones that have created a global network outside of state sovereignty and democratic oversight, seem to be the antithesis of the ethos your work is based on. How do you deal with this? Is there an epistemological conviction that allows you to go on with your work?

LIAM YOUNG

The good news is that all the systems, all the infrastructures, all the technologies we need are already here. They’re proven, they’re tested, they’re working at smaller scales around the world – and have been for 15 to 20 years. The crisis we are in now is one of the imagination. We’re in a cultural and political crisis of imagination. What that means is if you want to make work that meaningfully resonates in this context, it needs to have currency in a regulatory context as well as a cultural context. If battling climate change is about winning the hearts and minds of people, then we need to make work that resonates and connects with audiences on a scale much larger than that occupied by traditional design and architecture audiences.

The project of our generation is to try and find ways to be hopeful and committed when all evidence points to the contrary. That things will only get worse. Like I said, it’s a daunting and horrific place to be in but at the same time, everything is in place and if we wanted to, we could wake up tomorrow and do it. That is an extraordinarily wonderful position to be in. We’re a generation that have both the means to diagnose and understand the problem, and have the technology, systems, and capacity to solve these problems. We just need to get out of our own way.

M&B

One of the things your work certainly highlights is the painful absence of a collectively shared imaginary. Simultaneously, one of the things that makes your work so controversial is what I would perhaps call its “neo-modernist” character. Developing such a confident vision at that scale very much goes against the tide of work that’s being done in the fields of speculative art and design. The great majority of your colleagues recoil from addressing the techno-industrial global infrastructure, instead going for small-scale interventions since at least they are doable. There are also those who vehemently argue in favour of a retreat of human agency, who take the position that humanity must take a back seat and show humility. And then you also you have the entire post- and decolonial discourse that would denounce a vision like yours as just another version of colonisation. You said that we need to reach broader audiences but still, do you see a way of winning those colleagues over?

LIAM YOUNG

At the core of my work is an extreme pragmatism. The world literally is on fire. The time for platitudes, conciliatory action, and finger pointing, is over. We can’t afford to be pleasing everyone. We just need to find the shortest route to doing the things that we need to do. This is really what this work is borne out of; searching for the types of images and stories that we need right now. I totally empathise and deeply agree with narratives around climate justice, restricting human growth, and making space for other species, making space for other kinds of ecosystems, and so on. We desperately need to be doing all these things, but the language through which we talk about them is, especially here in the US, is hugely divisive. The moment you talk about something like climate justice, you immediately alienate those on the political right and there’s just no time anymore to fight those kinds of battles. We create imagery that, hopefully, resonates on both sides of the aisle.

Reef City still from After the End, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist.

When we make a work like The Great Endeavour, we can talk about it as a process of decolonising the atmosphere. We can talk about it as a process of reversing the infrastructural acts of colonisation and exploitation that have characterised the Industrial Age. Yet, we can also talk about it in in terms of the bravado or machismo of building big again, we can talk about it in the context of creating jobs.

So, there are ways of framing the necessary things and scales of action that we need to do. Ways that that don’t divide. Again, I think the project right now is to narrate these actions in ways that resonate with how both the left and the right want to imagine our future. We don’t need to talk about addressing climate change as an act of retreat. We don’t need to talk about it as a form of penance that everyone needs to go through and suffering that awaits us. We can talk about it in a way that allows us to maintain and live out the lives that we all love, and that only the naivest would imagine us giving up. We can talk about it in ways that hopefully make sense and work. It is trying to say: we can do this.

I think it is a near modernist work but not in the sense that it’s some single lone genius that constructs a utopian plan and then rolls it out across the rest of us. Rather, it’s a process of trying to build consensus across all aspects and landscapes of the political map.

M&B

This sounds like a version of what Mark Fisher called “popular modernism.”

LIAM YOUNG

Yes, exactly. Fantastic. I mean, that’s it! To go back to your point about how and why we keep going; I’m also a massive science fiction geek. I do believe that this type of imagery around the future has a really important role to play right now. The technological infrastructure that shapes our contemporary life has arrived faster than our cultural capacity to understand it and what it might mean. That suggests that the role of this type of imagery is now critical. Science fiction used to be about the wondrous speculation and imagination of things to come. Do you remember The Jetsons? A sci-fi animated kids TV series that came out in the 60s. It imagined interplanetary colonisation, food in pill form, jet packs, hoverboards, and so on. Its role was to fill us with awe, wonder, and dreams about what the future could bring. What we’re seeing now is that this type of imagery isn’t speculation and imagining what could come but rather it is a way of rationalising and helping us understand the implications of the technologies that are already here. Technologies that have outpaced our imagination.

The role of these science fiction images today is to try to think about how we can implement and roll-out the necessary infrastructural changes to meet the various crises that we’re talking about. We must narrate the present and re-narrate technologies that have been created yet, finding ways for them to be implemented that we are yet to imagine. There’s an urgency for these images now. One that was not there for previous generations.