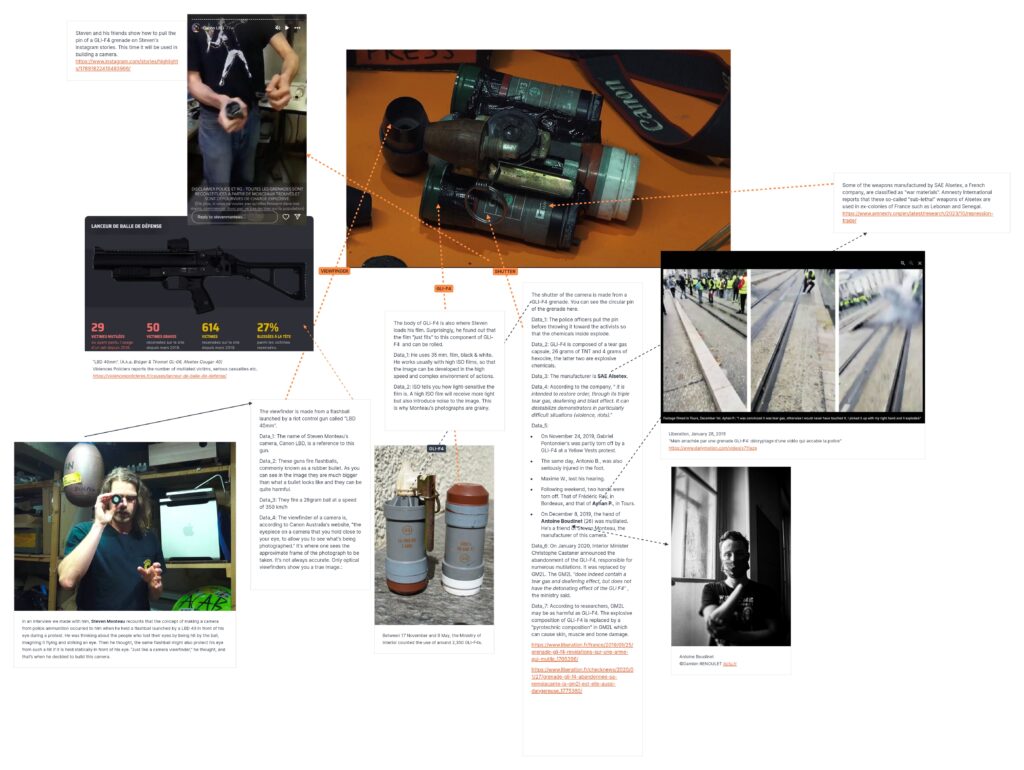

On November 22, 2023, an article appeared on VICE Belgium titled “Een camera maken van politiewapens” (Making a camera out of police weapons).1 The piece told the story of photographer and art gallery technician Steven Monteau, who, along with his friends, began collecting police ammunition that was left on the streets during the Gilets Jaunes (Yellow Vests in English, which was a predominantly working-class movement against inequality and the rising cost of living that began in 2018) protests in France “to learn more about the weapons littering the city.”2 Having been part of a collective called Le Volcan (The Volcano) and involved in the practices of upcycling, Monteau created a camera made of police weaponry and started taking photographs in demonstrations using this camera itself. Eventually these photographs were pasted on city walls for the eyes of passersby.

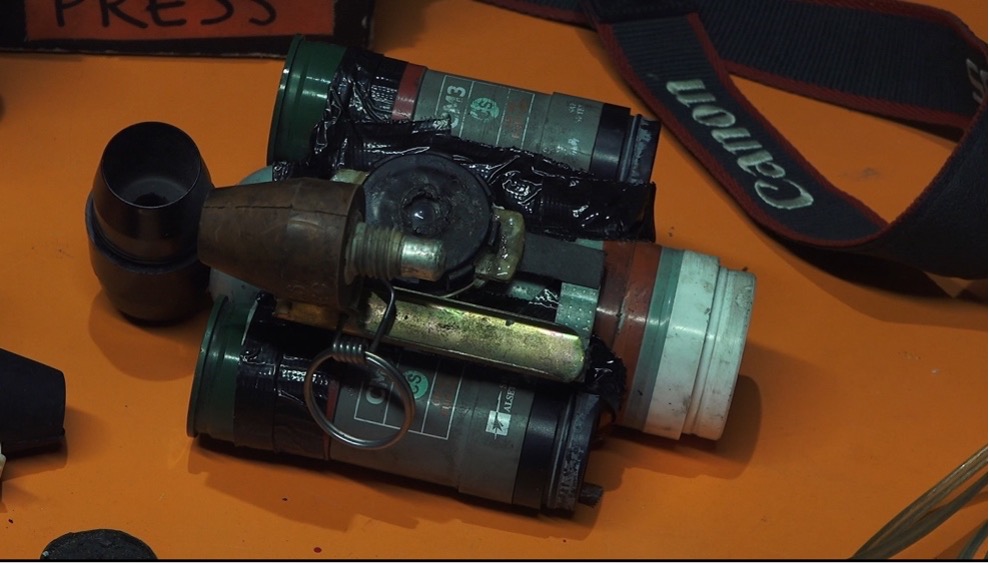

The camera made by Steven Monteau: the 'Canon LBD'. Photo by Image Acts

As the Image Acts duo, we came across this article while in the early stages of developing a documentary about the history of camera builders, particularly Paul Delesalle, an anarcho-syndicalist and precision instrument worker, who built one of the first cinematographs for the Lumière Brothers.3 Despite being one of the laborers behind the capturing of the first moving images, Delesalle was not even invited to the first screening of Lumière Brothers’ films.4 While reflecting on the image production processes and the invisible labor involved in creating cameras, as illustrated by Delesalle’s story, we felt compelled to connect with Steven Monteau, who could be regarded as a contemporary counterpart to Delesalle.

A few weeks later, we were pointing our (factory-manufactured, digital) cameras towards Steven’s camera in his atelier in Bordeaux thinking: What is this object that is somewhat reminiscent of both old items of army ordnance displayed in a war museum and Dadaist sculptures like Raoul Hausmann’s Mechanical Head or Jean Tinguely’s Métamatics? An oddly beautiful, bulky yet operative, homemade analog camera, nodding to the situationist tactic of détournement with its body composed of the so-called sublethal weapons and kinetic impact projectiles of the French police.5 High-tech police weaponry made of metals, plastics, rubber, and foam, detourned into a camera that attempts to document police violence and capture moments of solidarity. Didn’t the Situationists say that any elements, no matter where they are taken from, could be used as an arsenal for revolutionary propaganda? This text consists of short reflections on this artifact as a psychogeographical tool that navigates, studies, and intervenes in the spatial, political and emotional terrains of oppression and resistance.

From Étienne-Jules Marey’s Fusil Photographique ‘Rifle’, an early prototype of movie cameras, to the advancements in lightweight cameras in conjunction with military technologies, the striking and disturbing links between cameras/images and warfare/weaponry has been a point that is hard to miss in the debates on the subject. Steven Monteau’s naming of his camera, Canon LBD, highlights this link by combining signs from the image industry (Canon) with those from the arms industry (LBD, an abbreviation of lanceur de balles de défense, defense ball launcher). The physical structure of the camera follows the lead; it is constructed by hijacking weapons and ammunition used in riots against protesters, left behind by the French police. Steven began collecting these remnants from urban environments after his friend, Antoine Boudinet, lost a hand due to a GLI-F4 grenade – a device containing 26 grams of TNT and 4 grams of hexocire – fired by police during the Yellow Vests protests in Bordeaux during 2018.

Steven holding a flash-ball in front of his eye. Photo by Image Acts

Moving back to Steven’s atelier in Bordeaux: while we film Steven and his camera, he collects a flash-ball from a box of ammunition gathered from the streets and holds it up to his eye. He explains that the idea of creating a camera from police ammunition occurred to him when he held one of these flash-balls, launched by an LBD40, in front of his eye during a protest. He imagined a bullet flying toward him and striking his eye. At that moment, he thought, “It’s just like a camera viewfinder,” and realized that it could serve a dual purpose: not only could it protect against flash-ball fire, but it could also capture their images.

Eventually, the pin from the GLI-F4 grenade that injured Boudinet became the shutter of the camera. The balls, bullets, gas canisters, and grenades that were once filled with explosive chemicals and launched at the protesters are transformed by Steven into a device that captures light and generates images. While Canon LBD reclaims the enemy’s weapons for its own use, it remains an object that serves as a reminder of the unsettling resemblance of a camera to a weapon; surveilling, classifying, capturing, shooting… Steven describes what he does with this camera as “an eye for an eye.” He refers not only to the act of turning the police’s weapons against them but also to the eye looking through the camera, representative of the eyesight of his comrades taken by police violence.

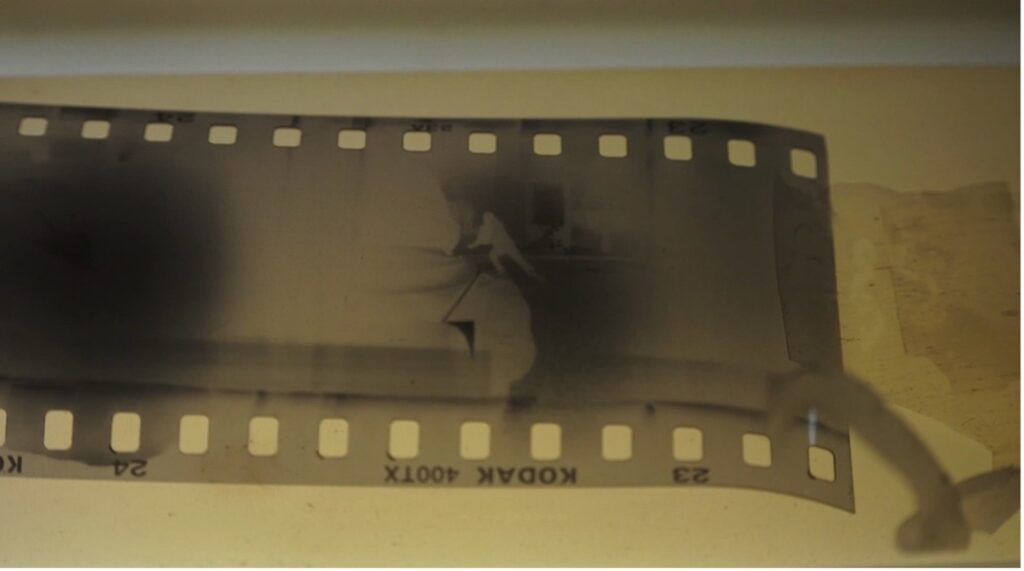

Most figures and spaces in the images produced by Canon LBD appear blurred, whether they depict the police or the protesters. This blurriness results from the camera’s fixed focus. Steven compares it to the effect of squinting in a cloud of smoke. He cannot adjust the lens for clarity; instead, he must move back and forth, adjusting the distance between himself and the subject. In other words, he aligns himself with the reality of each moment, navigating its emotional and spatial contours as he captures a brief but shared experience – the passage of a few people through a rather brief unity of time. The mechanism for advancing the film roll is also unpredictable, relying on Steven’s intuitive handling. This often leads to overlapping frames, creating spontaneous and layered juxtapositions of resisting bodies – essentially forming half-random collages of collective dissent. The exposure levels of a single photograph taken with Canon LBD are influenced by the intensity of physical repression and the movements of the protesting bodies. This gives the images a unique immunity to detachment from their original context and from the stiff psychogeography of the moment and place. Art and its surroundings become inseparable.

Let’s imagine Paris’ Place de la République or Place de la Nation during the Yellow Vests protests, in the city once described by Debord as: “From any standpoint other than that of police control, Haussmann’s Paris is a city built by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”6 One only needs to drift into the city and turn their eyes to the ground, particularly after a protest, to see how the crowd of people has been replaced by a crowd of leftover pieces of weaponry: Hundreds of tear gas canisters and grenades left on the streets of the city, used and discarded. From “any standpoint other than that of police control,” it would look like an enormous chemical dump. Preferably with gloves on, Steven and his friends collect these deserted weapons that were just wielded by one of the most violent police forces in Europe.7 They use trash as a means of production. In a way, literally “creating a new weapon out of a former weapon’s ruins.”8 They expropriate these materials, taking back from the enemy “those properties that the enemy has transformed into weapons against the dispossessed.”9

An Instagram story by Steven Monteau, depicting the ammunition found on the street after a protest

The simple gesture of the body taking semi-arbitrary routes after the protest and looking down while walking becomes a way of studying the political and emotional space of a heavily policed city. Trash, here, not only serves as evidence of police violence but also a ghostly marker of the resilient bodies that continually return to the streets. The images that will eventually be produced by the camera made from these pieces will embody this labor involved in collecting and assembling, a form of labor that capitalism has historically attempted to render invisible since the rise of industrial image production (does anyone remember Paul Delesalle?)

Canon LBD is not a nostalgic artifact; it is crafted from some of the most advanced components of police ammunition. Its appearance resembles a weapon more than a camera, making it an object that could be detained, confiscated, or seized. This stark contrast of Canon LBD with, for instance, vintage cameras has tangible consequences: Steven recounts instances where he was interrogated by police simply for carrying the camera, mistaking it for an explosive device rather than a tool for photography.

Although Canon LBD’s body is made up of high-tech components referred to as internal security weapons, intended for use “where security personnel have no other means of defense,”10 it is in fact a rather fragile machine. When shaken by the movement of the people or police batons during the protests, as Steven tells us often happens, the camera can capture too much light that leads to overexposed photographs, which ironically appear more “artistic” than evidential. Steven mentions that sometimes when he develops the film rolls, nothing comes out – no images, no documentation. There are overexposed 35mm frames on a film roll of 36 frames. White on the negative (the film), black on the positive (the print) – absence of representation. By being receptive to the marks of violence, the camera highlights the tangible nature of what we call an image. This constructed situation emphasizes the paradoxes of trying to document police brutality with an unreliable camera, especially in a time when everybody has a high-quality digital camera in their pocket. But perhaps more than that, it stages a playful rejection of the necessity for a visual outcome, of the spectacle itself, in favor of the body in action, the act of collecting and assembling, and a ‘possible rendezvous’ with other protestors.

Steven assembling his camera before the May 1 march in Paris, 2024. Photo by Image Acts

Canon LBD perhaps also symbolizes a resilience that characterizes the diverse class subjectivities and temporal strategies seen in the Yellow Vests movement. Comprising mainly of blue-collar workers and small business owners, the movement was disorganized, yet capable of coming together at any time and place without prior notice. Like the body of a Canon LBD, held together with bandages, the Yellow Vests represented an organizational entity that could be broken down, yet reassembled.

When Roland Barthes described how being photographed both “creates and mortifies” the body, he invoked the fate of certain Communards during the 1871 Paris Commune, “who paid with their lives for their willingness or even their eagerness to pose on the barricades: defeated, they were recognized by Thiers’s police and shot, almost everyone.”11 Becoming an image – whether through revolutionary aspirations or the forces of capital or commodification – has always signified an in-betweenness, a duality of immortalization and mortification. The photographic image, as a product of industrial capitalism, has embodied this paradox since its invention.

One of Steven’s photos, depicting an activist throwing a rock; developed on a Kodak film roll, black & white negative 35 mm, ISO 400. Photo by Image Acts

In her article published in the compendium Capitalism and the Camera, Siobhan Angus reminds us that “photography is light drawn in silver.”12 Both the film and printing paper of analog photography rely on a chemical process of emulsion that necessitates silver. The existence of the photograph as a material object depends on natural resources and human wage labor required for this extraction. Angus gives a revealing example, hinting at the essential paradox behind the photograph: In a photo postcard from 1907 we see a crowd of miners gathered in a town square. Silver was used in the production of this very postcard of miners who were carrying out a general strike at the Nipissing Mine in Cobalt, Canada. The images intended to document the workers’ resistance against their exploitation were, paradoxically, created through the very modes of production they were protesting against.13 How does Canon LBD embody these paradoxes? Aren’t the images that will in turn become markers of violence and solidarity alike also products of practices of extraction? Steven’s photographs do nothing to try hide this; the names of the global industrial image production companies are left clear to see, framing his images.

Steven’s photographs printed on paper, depicting moments of solidarity and empowerment. Photo by Image Acts

Canon LBD embodies a psychogeography of the present marked by the riot control technologies turning the cities into chemical dumps and activists searching for alternative modes of image production, amid an age characterized by hyper-surveillance and increasing abundance of spectacles. Though, this psychogeographical cartography is not limited to the happenings of a modern metropolis and European capital. The riot control strategies used by the French police have a long colonial history. Explored in detail by independent researcher Mathieu Rigouste, the model of counter-insurrection used in modern cities of France was appropriated from the military’s management of settler colonies. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, these counter-insurrection technologies and apparatuses would be adapted for the capitalist urban landscape in Europe, brought into the domain of police, and subsequently exported back to the colonies for additional profit.14 A similar colonial route can be traced through the material used for Steven’s camera. SAE Alsetex, one of the companies that manufactures the tear gas grenades and flash-ball launchers used in making the Canon LBD, exports these weapons to the former colonies of France. They are utilized in Senegal and Lebanon for multiple purposes, including riot control and counter-insurrection.15

Hence, the images produced by Canon LBD reflect not only the scars of contemporary metropolitan violence but also those of colonial violence. Today, the relationship between weapons and media imagery is more apparent than ever before. As the images of the ongoing genocide in Palestine are broadcast live on our screens, political struggles systematically attempt to map out neocolonial routes and render visible the flow of transnational arms and energy trade. Canon LBD camera and the images it produces prompt us to consider the origins of these bullets and guns, and the colonial trajectories that enable the extraction of mines used to create photographic images. This is how Canon LBD operates, as a psychogeographical tool, within the spatial, political and emotional terrains of oppression and resistance, both exposing its dynamics and collecting its material to intervene in it.

A work-in-progress mood-map we (Image Acts) designed for our documentary project.

Canon LBD reminds us of the lived experience that is entwined with the process of producing images in the space of oppression and resistance – collecting fragments of weaponry scattered across the urban battlefield and the visceral labor of placing one’s body within the turmoil of a riot, while confronting the threat of police projectiles, evoking the haunting memory of communards who fell beside the barricades. The eye that observes an incoming rubber bullet and perceives it as a viewfinder suggests a need for a new psychogeographical narrative. One that invites us to imagine ways of forming alliances with those who have been, and continue to be, targets of these same incoming bullets.