I’m the street you walk,

the language you talk –

I am the city.

In “Rise and Fall of the Daily Paper,” the Italian social theorist Marco d’Eramo starts his eloquent eulogy for the printed word (or more specifically, for the printed newspaper) with a great observation on the disappearance of the kiosk as an urban phenomenon:

Like all slow processes, this extinction is almost imperceptible. But then, one day you realize that the kiosk on the ground floor of Milan’s central railway station has gone, replaced by some shop selling tourist tat, and that among the tens of boutiques and plate-glass displays there is now just one newsstand left, on the upper floor, by departures. In Paris, what leaps to the eye is something that isn’t there: the piles of Le Monde, fresh from the printer, that ten years ago were dropped at two in the afternoon at every Métro entrance. On a Sunday, in any European city, it’s increasingly difficult to find a news vendor open. The stands themselves have also changed. Just as railway stations have been reduced to commercial centres in which trains seem a residual inconvenience, so the kiosks accumulate gadgets, DVDs, candy, lottery tickets and scratch cards while the few surviving daily papers are tucked away in a corner, as if accommodated for form’s sake. But what does this disappearance mean?

D’Eramo is correct in making the link between newspapers and the city, and for using the apparent decline of the kiosk as a measuring stick for the current state of printed matter. After all, the kiosk is the original interface between the printed word and the built environment – the place where the graphosphère manifests itself in the city, in its most concrete form. As such, the kiosk has always been a modernist trope, a para-architectural device designed to turn the city into an infrastructure for language.

It was in the avant-garde movements of the 20th century that the theme of the kiosk was explored to the fullest. While Constructivists envisioned kiosks as semi-mobile sculptures, broadcasting revolutionary agitprop (see, for example, Gustav Klutsis’ utopian multi-media structures), and Futurists such as Fortunato Depero came up with heroic book pavilions, Bauhaus-affiliated designers imagined spectacular magazine stands, incorporating large advertising billboards (Herbert Bayer’s designs for newspaper and cigarette kiosks come to mind). In other words – artists and architects (from groups ranging from De Stijl to Dada) had a vested interest in the idea (and format) of the kiosk, and rightly so. The kiosk symbolised the synthesis of art and the everyday, of theory and practice, of “high” and “low,” of time and space – in short, the whole of modernism itself.

A present-day disappearance of the kiosk would thus not only signal the decline of the newspaper, but also the end of an idea, of a modernist ideal – the notion of the city as a public platform for speech, as a network for the democratic dissemination of information, as a vibrant circuit for signs and signals. With the current mass-digitisation of data, the distribution (and consumption) of information seems to have turned inwards – from the outdoor to the indoor, from the public to the private, and from the visible to the invisible. Or at least, that’s what theorists like D’Eramo suggest.

Deschooling Society by Ivan Illich (Penguin, 1971), with a cover by Omnific (Derek Birdsall). Found at a street library on Javastraat, Amsterdam.

And yet, and yet. In our own perception (as avid walkers, and thus as avid readers, of the city of Amsterdam) the significance of the decline of official kiosks pales in comparison to the massive growth of so-called “little free libraries,” as presently seen throughout the streets of most European capitals. Of course, the sharing of free goods through specific spots in the city (not to mention the more general idea of the “gift economy,” the potlach model, etc.) is nothing new – but during the past two decades, the notion of the public bookcase has really solidified, and slowly gained a steady foothold within the urban environment. Finding its origins within the history of public book exchanges that goes back to the 18th century, if not earlier, and a recent reemergence (at least in Western Europe) as manifested by the Little Free Library movement founded in 2009, the BookCrossing initiatives of the early 2000s, and German communal art projects in the early 1990s, it is only now that the full impact of these street libraries has become visible.

Our own (uneducated, and quite intuitive) guess regarding the reason behind this sudden boom of bookcases is two-fold. On the one hand, we assume the growth of street libraries is connected to the disappearance of an older, more “book-ish” generation. We are thinking here of the curious (and deeply melancholic) phenomenon of “death-cleaning,” and the notable shifts caused by elderly people moving to smaller houses (or sadly passing away) – with large chunks of private libraries suddenly appearing in the streets. One generation’s death-cleaning being another generation’s life-hoarding, these books quickly find a new audience – through an alternative network of make-shift kiosks, an emergence that only seems to have been accelerated during the pandemic years between 2019–2022 (a period characterised by a paradoxical mixture of indoor and outdoor activities – cleaning, clearing out, and reading on one side, and the rediscovery of leisurely walking, in a tourist-free city, on the other side). Another explanation may be found in the recent digitisation of a certain kind of books – dictionaries, encyclopaedias, travel guides, scientific volumes, technical manuals, atlases, almanacs, annuals, telephone directories, textbooks, schoolbooks, sourcebooks, handbooks, cookbooks, and the like. Now that this information is often freely available online (dissolved into thin air – melted into the ether), physical books are experienced as unneeded ballast and are quickly unloaded into an ever-growing circuit of street libraries – turning the city into an extensive paper memory.

Future Shock by Alvin Toffler (Bantam Export Edition, 1970), with a cover by S. Neil Fujita (who also designed the jacket of The Godfather). Found at a street library on Entrepotdok, Amsterdam.

There exists a whole tradition of literature revolving around the idea of the city as a structure that can be read, not unlike a book – let’s call it a biblio-psychogeographic lineage. This history can be traced back all the way to the epic of Gilgamesh (one of the oldest works of literature), and the role of the city of Uruk (and its famed walls) within that story. The inscribed walls of Uruk basically symbolising the clay tablets on which the first Sumerian poems have been imprinted, the underlying (circular) theme of Gilgamesh seems to be the idea that the city is made by language, and language is made by the city (after all, Uruk is the source where both script and city originated – in their “Ur”-forms, so to speak). Skipping forward a few centuries (in fact, millennia), there’s of course the biblical story of Babel, in which the shattering of the city causes the scattering of languages across the world – another example of the deep connections between walls and words.

Drifting even further forward, there’s arch-flâneur Baudelaire, who famously described his natural surroundings as a “forest of symbols” in his 1857 Correspondences. Benjamin defined Paris as a “linguistic cosmos” in his Arcades Project (first published in 1982). Then there’s Barthes, who envisioned the city as a discourse – “the city speaks to its inhabitants, as we speak to our city.”1 Heidegger revealed the organic links between building, dwelling, and writing, in 1971 – “poetically, man dwells.”2 And for Debord, as fictionalised by Michèle Bernstein’s 1960 roman à clef “All the King’s Horses” in the character “Gilles,” walking through the city was the proper way of reading, studying, and doing research (“No, I walk around. Mostly I walk around.”)3

This way of thinking (the book being a model for the city, and the city being a model for the book) spilled over in modern information technology as well. The Belgian utopian Paul Otlet described his “Mundaneum” (one of the earliest visions of the internet) as a “world city of information,”4 while the current internet still borrows a lot of terms from the city (a typical example being the word “forum,” referring to the classic Roman notion of a public square). In fact, one of the first Dutch internet providers, De Digitale Stad (The Digital City), was built entirely around the metaphor of a city.

Structuralisme et Marxisme, classic 10/18 paperback from 1970, with a cover by Pierre Bernard (but not the Pierre Bernard from Grapus though). Found at a street library near Haarlemmerdijk, Amsterdam.

In our view, the current reemergence of the “little free libraries” adds a fascinating new chapter to the biblio-psychogeographic narrative of the city as a structure that can be read, like a book. The link between the book and the city is no longer metaphorical now that actual books are flooding the streets, turning the city into a de facto library. In that sense, these public bookcases seem to fulfil the promise of a semiotic city via the unexpected return of the modernist model of the kiosk. What we are witnessing is nothing less than the migration of printed knowledge out from the interiority of the bourgeois living room into the messy exteriority of the urban landscape. Language being revitalised by the streets, while revitalising the streets in return. A true rebirth, rising from the ashes of both books and cities.

While staring at a set of books by various theorists of the Frankfurt School in one of these street libraries not long ago, it suddenly appeared to us that the arrival of these texts in the city can be seen as the realisation of what the late great Marxist sociologist Marshall Berman dubbed “modernism in the streets” – and what Mark Fisher referred to as popular modernism.5 Keeping in mind that some, though not all, of the thinkers associated with the Frankfurt School (Adorno most markedly) made a sharp distinction between “high”/avant-garde culture and certain kinds of “superficial” mass-culture (i.e., culture produced under monopoly capitalism), to now see those books resurface in the hustle-and-bustle of outdoor civic life represents something of a collision of worlds – if not a collision of words. Especially considering that on these make-shift bookshelves the writings of Adorno and his cohorts now rub shoulders with New Age self-help paperbacks, sci-fi pulp, and detective novels. It’s as if a forgotten species of intellectualism that was once caged safely within the zoos of academia has finally been let loose in the streets, running hungrily towards an unsuspected crowd.

Erich Fromm, Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (Fawcett Premier, 1970). Unfortunately, no designer mentioned. Found at a street library on Wijttenbachstraat, Amsterdam.

We already mentioned Baudelaire, Benjamin, Barthes, Bernstein, and Berman – to this “B-list” (so to speak), to which we would like to add yet another name: Borges. After all, if there is one idea that looms large above this new urban infrastructure of “little free libraries,” it’s the concept of ‘The Library of Babel’ – the model of the eternal, labyrinthine city, containing an infinite number of books, as described by Borges in his eponymous aforementioned short story from 1941. As a tale, “The Library of Babel” seals the many links between the book and the flâneur, and thus between reading (wondering) and strolling (wandering). The protagonists in Borges’ story are mystic librarians, drifting endlessly through geometric corridors filled with books that are as occult as they are standardised, trying to make sense of the undecipherable texts they come across. The modern wanderer roams the streets of cities like Amsterdam in the same way. They drift from one hidden library to another, browsing through vast rows of seemingly meaningless books, searching for that one out-of-print gem, that rare volume, that unexpected find. By strolling (sleepwalking, as in a dream) from one kiosk to another, the wanderer writes the pages of the city – weaving together impressions of half-read pages and fully-observed book covers, stringing the titles on spines together like one continuous sentence as they meander from street to street.

But it is not solely the wanderer who drifts in the case of these little kiosks. It is the library itself that drifts. Prime examples of mobile, parasitic architecture, these bookshelves seem to be constantly in transit. Moved, removed, constructed, deconstructed, destroyed and rebuilt, these little libraries lead a fluid existence. They are shape-shifting structures – sometimes appearing as ready-made closets, turning the interiority of city life inside-out as if hurled from the living room into the alleyway, sometimes taking the form of fantastic self-made constructions, sometimes even embodying the true spirit of squatting as they occupy already-existing structures like long obsoleted telephone booths. A drifting library – not only intended for strollers but involved in the act of strolling itself.

And let’s not forget the third drifting element: The books themselves. Like driftwood, these books migrate not only from the living room into the open space of the city (and back again) but also seem to circulate in-between libraries. To the frequent visitor, it is not uncommon to see a publication from one library suddenly resurface in another library – within a matter of days, sometimes even hours. A book, taken for a stroll, reconsidered, and put back into another library, inserted into another cluster of books, drastically reconfiguring the constellation of meanings found on these shelves. Indeed, again like driftwood, these books wash ashore in unexpected combinations – without any respect for category or genre, as if spat out by an anti-Dewey maelstrom. At any given moment, it’s not unusual to see the shelves filled with wildly different, contrasting, even opposing books – occult thrillers sharing space with philosophical treatises, political tracts fraternising with their worst enemies, horror epics exchanging spit with romantic novellas, non-fiction blurring the lines with fiction. To speak with Benjamin, this is exactly the environment in which “truth becomes something living – it lives solely in the rhythm by which statement and counter-statement displace each other, in order to think each other.”6

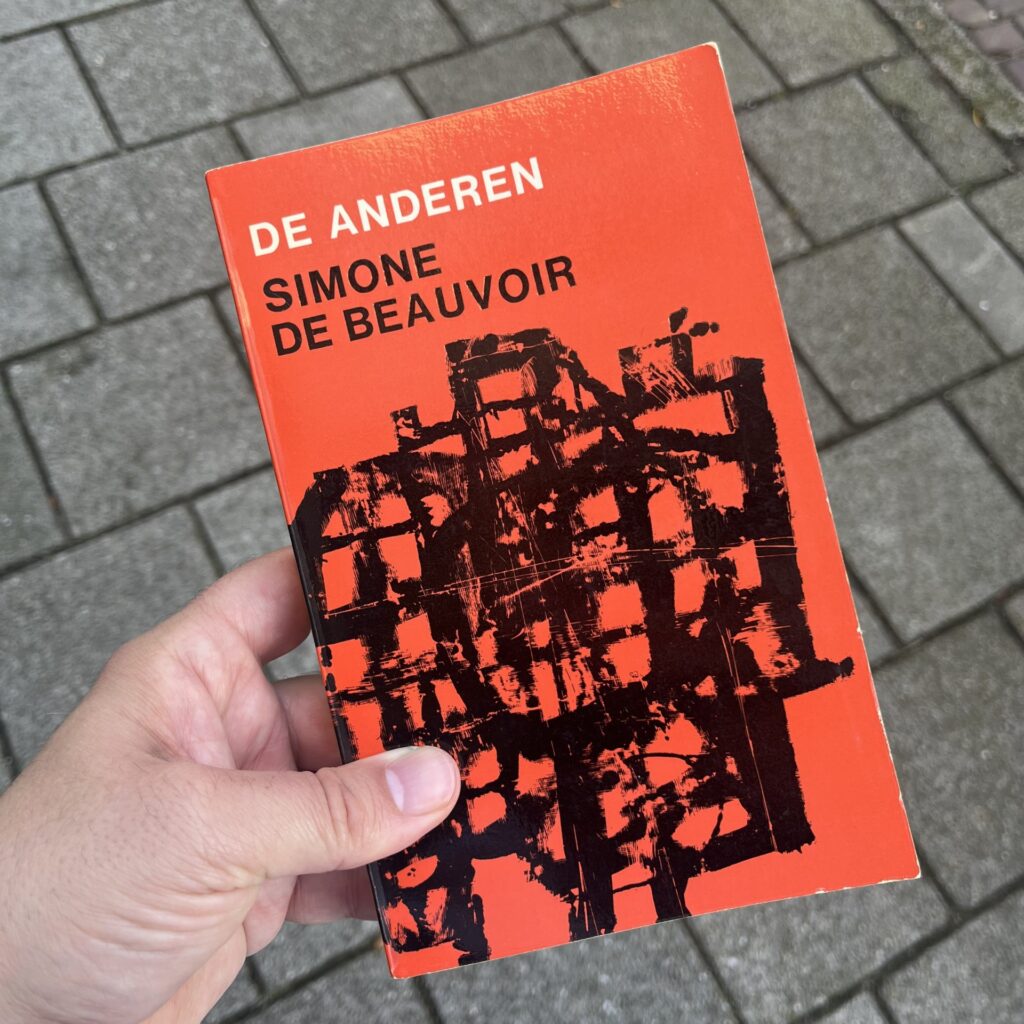

Simone de Beauvoir, De Anderen (Uitgeverij Unieboek / C. De Boer, 1969 – originally published as Le Sang des Autres in 1943). Cover by Max Velthuys. Found at a street library on Mauritskade, Amsterdam.

In that sense, the appearance of these kiosk-like street libraries, with their clusters of opposing knowledge, seems to cement a point we’ve been trying to make (admittedly, in our own often incomprehensible ways) already since 2011, throughout various interviews and articles – the idea that, in the end, there is nothing more progressive than the combination of printed matter and the city. As we argued in those texts – if a printed poster is hanging in the street, it is seen by every passerby in more or less the same way (sure, the interpretation of the poster will differ from person to person – but by and large, the poster itself will appear in roughly the same way to every viewer, regardless of their class, ethnicity, gender, age, personal preferences, and so on). This is different on the internet, where websites and -pages conform themselves instantly to cater to the personal tastes and preferences of the individual reader (Google search results change from person to person, the advertisements that clutter online feeds are specifically targeted toward that user, etc.). This makes the online environment ultimately an individualistic, isolated experience, despite the promise of “being connected.” It also makes most online activity a somewhat undialectical affair, as you only will be confronted with stimuli that are algorithmically curated for you, based on what large corporations (such as Meta and Google) expect you to want to see (look for example at the way algorithmic companies, such as Cambridge Analytica, have helped both the Brexit and the rise of Trump, and it seems clear that these kind of online infrastructures are ultimately creating isolated “bubbles” – feeding “culture wars,” conspiracy theories, and echo chamber ideologies) – whereas, within the context of the street, you will be confronted with information that is not specifically intended for you: advertisements that might never have had a chance at your interest, slogans you might disagree with, kiosks carrying newspapers that are not necessarily tailored towards your preferences, book stalls displaying paperbacks expressing conflicting opinions, and so forth. In our view, it is exactly this notion of print culture within the urban environment that offers the most dialectical, and therefore most progressive experience.

The recent manifestation of these free little libraries (or, as we might call them from now on, ‘drifting libraries’) emerging in cities all around the world, adds a fascinating new chapter to this story, this ongoing relationship between the streets and the printing press. There has been a lot of talk about the end of print (and the end of the city has been proclaimed as well) – but in our view, an opposite movement is on the rise. What seems to be a symptom of a world that is slowly but surely ‘de-booking’ itself (with older generations disposing of their private libraries, and books being discarded because of the ongoing process of digitisation), has actually caused a reverse tendency – the resurfacing of these books in the streets, an unexpected revitalisation of the bonds between the city and the printed word, and a rediscovery of the links between reading and walking. It’s part of a tradition that runs (or, drifts) from the imprinted walls/tablets of Gilgamesh’s Uruk all the way to the impromptu kiosks and make-shift libraries in the hidden alleyways and windy avenues of our modern cities. So let our feet do the reading, our eyes do the drifting – and answer the call of this current semiotic cityscape. Let’s forget the old, tired routes – and start weaving a new web of words and streets, overlaying the existing city with a linguistic labyrinth of our own making (and breaking). To walk is to read, and to read is to walk – and the rest remains to be written.

Experimental Jetset

Amsterdam

October 29, 2024